Back To The Shack

RadioShack’s recent troubles might best be reflected by the recent auction of its corporate history—an auction that is actually full of interesting gadgets.

Quick shoutout: Thanks to everyone helping us out via Patreon, especially Ari Weinstein, whose app Workflow was acquired by Apple earlier this year. (We featured his interesting hobby a while ago.)

Maximize Employee Retention, Productivity & Happiness We host company team building events at the world’s best museums. NYC, San Francisco, Chicago, Washington DC & Los Angeles. Includes fun activities, group photos and more. Rated top 10 on TripAdvisor by companies like Google, Facebook, Etsy, Adobe & Oracle.

Today's issue is sponsored by Museum Hack. (You can sponsor us, too.)

Flavor in your ear: These tiny, colorful transistor radios were extremely hackable

RadioShack was famed for its numerous private label brands—most famously under its longtime parent brand Tandy (which, no kidding, started as a leather goods company before it took RadioShack national in the 1960s), but also Optimus, Archer, Micronta, Science Fair, and a few others.

The most visible of these brands, however, was Realistic, which the company launched in 1954 under the name Realist. The Realistic brand covered a number of electronic products, but perhaps the most famous ones were the Flavoradio portable radios—which usually were sold in AM-only formats, but later as AM/FM devices. A set of three of these devices is currently selling in the auction for $32.

For roughly three decades, RadioShack sold these transistor radios, which were notable for both their simplicity and their color scheme.

The simple design and low cost, of course, made them quite hackable. In 1989, the amateur radio-focused 73 Magazine wrote a cover story titled “Flavorig!"—a tale of how to turn the cheap device into a CW (Continuous Wave) transceiver, a common mode of ham radio communication associated with Morse Code.

“Enjoy your Flavorig,” author Michael Grier wrote in the issue. “For such a simple beast, it works remarkably well. Once you make a contact on a rig you built yourself, you may find that ‘940 gathering dust while you experience the thrill of pounding out your call on a 5 watt box!”

It wasn't the only hack of its kind, either: One user, inspired by a magazine article, figured out how to take the roots of the Flavoradio and turn it into a shortwave tuner.

“It wasn't fantastic (there was an awful lot of spectrum crammed into the 180 degree rotation of the tuning knob), but it worked well enough to bring in a surprising number of broadcasts, and exhibited an amazing ability to select a single signal out of a big pile of stations all lumped together,” Patrick Innes wrote on his Earthlink site in 2001.

It may have been intended as a cheap radio for mass consumption, but it was secretly a Raspberry Pi for radio-heads.

“It’s obviously an electronic upgrade of the old fortune-telling Magic 8-Ball, though it lacks the poetic spirit that could express sentiments such as ‘Future Hazy Try Again.’”

— A 1984 article in PC Magazine describing the Executive Decision Maker, a gimmicky product that reminds folks that RadioShack, when it wanted to, could take on The Sharper Image toe-to-toe. The device, up for auction here basically relies on a series of LED lights that float around and land on a series of six options—an approach which can be seen in action here.

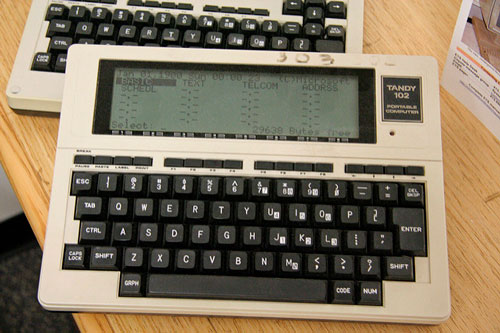

The RadioShack Tandy 102. (mk97007/Flickr)

RadioShack’s most influential computer might have been a portable device with a tiny screen and a full-sized keyboard

The TRS-80 Model 100 and the Tandy 102 computers were never particularly powerful machines—just small ones, ones that spoke to what would prove to be an important trend in the long run. Based off of the company’s better-known TRS-80 desktop computer, the devices came about in the late ‘80s as a way to write simple programs and quick text files.

First released in 1983 as the TRS-80 Model 100, it was one of RadioShack’s most consistent sellers, originally sold with the tagline “The Micro Executive Workstation.”

In a 1984 book on how to use the TRS-80 Model 100, author Kensington Lord noted how impressive the scale of the machine was, considering its functionality.

“Thirty years ago the computer was larger than most houses and consumed enough power to light your neighborhood. It required enough air conditioning in a single day to cool your house for a week,” Lord wrote. “Those who worked with the machine were trained in mathematics. The programs were literally wired into the machine. Today the computer weighs less than a sack of sugar, is programmed in simple nonmathematical language, and can communicate with other computers a room ... a city ... or a world away.”

Despite its design looking closer to a portable typewriter than a laptop—and despite the device basically being a svelte version of the TRS-80 Model 100—the Tandy 102 earned positive notices, with the New York Times recommending the machine to college students as a note-taking device. The device was also said to be popular with journalists in the pre-laptop era. A review from InfoWorld’s Mark Stephens suggested the device was much more useful than a similar portable product from Atari, the Portfolio pocket PC.

But the problem was that the device never really evolved all that much after its original release. The 102 shifted the form factor of the 100, but didn't push things forward enough to ensure the platform’s long-term success.

“In the documentation, packaging, and on the 102 unit itself, there are no copyright dates more recent than 1985,” Stephens wrote. “This is old technology, designed to do a good job for reporters, salesman, and others who need to prepare and transmit short text files.”

But that said, a later machine that was slightly less functional, the AlphaSmart 3000, earned rave reviews from writers not too long ago after its lack of distractions was held up as a virtue. One has to wonder whether RadioShack missed a market opportunity by failing to keep this device up with the times.

Five of the weirdest non-technology-related items in the RadioShack auction

- Put The Hammer Down, a compilation record of country songs about truckers, was produced by RadioShack in the 1970s in the midst of the CB Radio craze—a craze that, obviously, RadioShack benefited from. Among the items up for auction is the gold record that the album earned, because of course it is. You can listen to the complication over here. Yes, “Convoy” is on the record. (It’s not the only CB radio-related gold record in the auction, either—the more specifically CB-themed All Ears is there, too, along with a “gold record changer,” for some reason.)

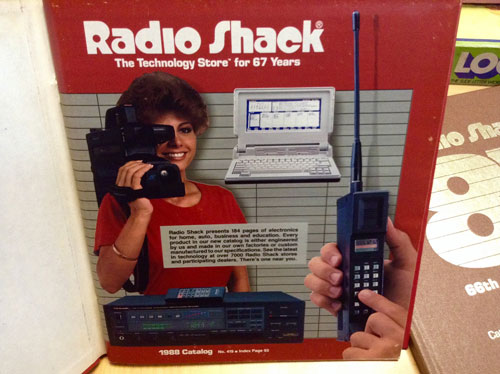

- An array of the company’s catalogs, which highlight the company’s formidable product lines over the years, are available in the auction—though if you don't want to bid, the website RadioShack Catalogs faithfully recreates most of them.

- A variety of art pieces that you can imagine hanging around the company’s offices, many of which are artistic takes on coffee cups. There are a lot of random coffee cup paintings in this auction. I'm not kidding.

- Autographed biking jerseys reflecting the not-long-ago period that RadioShack sponsored a bicycle racing team led by Lance Armstrong. That, infamously, didn't end well. Other weird sports-related items in the auction include a signed picture by Derek Jeter and two separate NSFW-ish signed photos of Ronda Rousey.

- And most depressingly, signage from the Tandy Store and Museum—that’s right, the company is so dead that the signs for its corporate museum are for sale. (Makes you wonder whether the old technology came from the museum.)

The GRiDPad, an early tablet computer. (OldComputers.net)

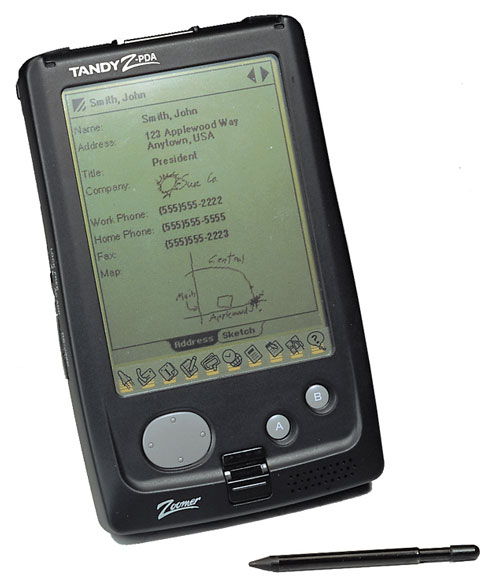

RadioShack helped set the stage for the PalmPilot’s success

Jeff Hawkins‘ fingerprints are all over the modern computing industry—literally. The founder of Palm Computing and Handspring was responsible for creating two devices—the PalmPilot and Treo, respectively—that defined the modern audience for touchscreen computing, even if that audience isn't actually using the Palm platform today.

And, as highlighted by two items in the RadioShack auction, he wouldn't have gotten where he was without the retail chain. The GRiDPad, a device formulated by Hawkins in 1989 for GRiD Systems Corporation. GRiD was an important early company for portable computing, with its GRiD Compass 1000, an early clamshell-based laptop, showing up on the Space Shuttle in 1985. But by the late ‘80s, the firm had been picked up by Tandy, which meant that the GRiDPad had a place in RadioShack’s history.

“This is not a laptop; it’s a new tool entirely,” GRiD marketing manager Kenneth Dulaney told Computerworld of the device in 1989.

Unlike most of the stuff under the Tandy umbrella, the tablet-sized devices found niche uses not with consumers, but with businesses and corporate users. Detroit Edison, the energy company, used GRiDPads to track downed power lines—a significant upgrade from paper and pen. And police departments, like the one in West Palm Beach, Florida, also used the device, complete with custom software, for paperwork purposes. A South Florida Sun Sentinel article from 1992 compared the device to “a high-tech Etch-A-Sketch tablet.”

According to Hawkins, the device was actually a sizable success, selling $30 million worth of units in a single year at its peak. But the average person was slightly more likely to run into the Zoomer, a device sold by RadioShack under the Tandy brand name and formulated by Hawkins. GRiD wasn't a part of the equation because they weren't really interested—their business model was B2B, not B2C, and they weren't ready to change that.

“They saw it as just too big of a risk,” noted Geoff Walker, GRiD’s director of OEM Products, in comments to Pen Computing. “GRiD was focused on vertical applications of laptops and the GRiDPAD, and to start an entirely new product area aimed at consumers was seen as too divergent from the company’s mission and focus.”

(via Pen Computing Magazine)

While Hawkins couldn't get GRiD on board, Tandy did see the value of the Zoomer idea, which became Palm Computing’s first product. The device was built on the GeoWorks operating system, manufactured by Casio, and marketed by Tandy. Unfortunately, the public wasn't so convinced. Being very early to market, its hand recognition wasn't good, it was way too slow, and its sales were anemic, with the device selling just 10,000 units in its first few months of release. But Hawkins learned something important that helped make his follow-ups more successful.

“What I learned through this process is that these computers are not little PCs. They cannot be designed by committee, because the Zoomer was designed by committee,” Hawkins told Pen Computing. “You have to go against conventional wisdom in many aspects. We didn't know this when we built the Zoomer, we had a lot of problems in its design and we learned a tremendous amount doing it.”

Hawkins‘ takeaways from this process became the base of the PalmPilot, and while RadioShack and Tandy weren't involved in that, it likely wouldn't have come to being without them.

The thing about RadioShack as a company is that it always was built around two competing sets of audiences—the general mainstream consumers who would walk into its stores and buy cheap trinkets or family computers, and the generations of hobbyists who recognized the company as something more fundamental: For decades, it was the rare company that sold computing devices to Main Street.

In a lot of ways, the fact that it survived in strip malls rather than in big-box stores was the reason for its early success and a driving factor in its downfall.

In an era when NewEgg, MassDrop, and Amazon can happily cater to tinkerers without putting on a song and dance for mainstream computer users, it suddenly strips the value from RadioShack’s basic idea.

About a month ago, I wandered into a RadioShack store that was closing up shop, and I spent more than half an hour looking at the drones, the microphones, the vintage private label stuff, and the random plugs that had been there for 20 years, hoping to find something on clearance that would knock me off of my feet as a must-buy.

Despite the fact that everything was as much as 60 percent off, I couldn't find anything I truly wanted—and that kind of left me speechless.

At some point RadioShack disconnected from the consumers that actually cared about it and focused on the ones that wanted a cheap trinket or an object that could be purchased literally anywhere else.

Considering the deep history hiding in this auction, that’s a damn shame.

--

Editor's note: This piece first appeared in Motherboard, which often syndicates Tedium articles after the fact. We flipped the order this time.

:format(jpeg)/2017/06/tedium060817.gif)

/2017/06/tedium060817.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)