When Atari Was Politicized

The story of how the “Atari Democrats” came to shape the way politics and technology work together, for good and bad.

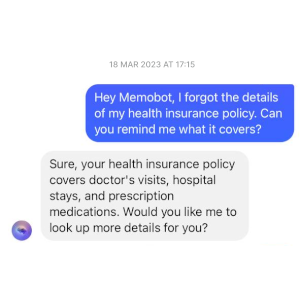

Sponsored By Remindful

Never forget anything important again. Remindful is an external memory for people with busy lives. It’s like an endless notebook where you can get instant answers about anything you have stored. It works in messenger apps like Whatsapp.

The kind of Democratic Party that found something to believe in with the “Atari Democrat” movement

The story of Atari is one that’s known quite well—a couple of engineers came up with the idea to start developing computer games for the arcade, then came upon a massive hit in the form of Pong, a success that eventually gave the company a path into the home through the Atari Video Computer System, later known as the Atari 2600. The company then expanded in ways that were pretty good (the Atari 400 and 800 computers, the Lynx) and pretty bad (the Atari 5200 and Jaguar), and ultimately lives on today as video gaming’s best-looking brand.

It didn’t last, but it sure was exciting while it was first happening.

Although stories about Atari have since highlighted a sexism-tinged company culture that feels very much out of step with the modern world (even if not everyone feels that’s fair), Atari was often held up during the late 1970s and early 1980s as an example of business innovation at its messiest and most fascinating. Move fast and break things was a phrase that fit Atari perfectly.

With that in mind, it’s easy to see why politicians wanted in on this kind of discussion. Atari wasn’t just a success story—it was an American success story, even if it had a name with a Japanese inspiration point. It was also a pretty hip company, run by people with shaggy hair and a disinterest in dress codes.

The term “Atari Democrat” started being bandied about around 1982, during the early years of the Reagan administration, among a group of Democrats who were more centrist in nature, not trying to push the Great Society ideals that were in vogue in the Democratic Party during the 1960s, instead showing some degree of support to Reagan’s push for tax cuts and stated efforts to roll back popular social programs.

/uploads/Paul-Tsongas.jpg)

Chief among these figures was Paul Tsongas, a first-term senator from Massachusetts who didn’t quite become the icon Ted Kennedy did, but found a lane for himself thanks to his pro-business streak, which led to frequent criticism from the left and even a belief among some that he might switch parties.

“I grew up in a conservative ethnic Republican household; I know what it’s about,” Tsongas once said of his point of view, according to The Christian Science Monitor.

Tsongas very strongly bought into the line about Atari Democrats, and even used it himself in a March 1983 op-ed, writing:

Over the past three years or so, I have found myself identified with a growing cadre of young Democrats seeking to fashion a new Democratic agenda for the 1980s. We have been called New Liberals, New Wave, Turncoats, and Technopols, among other things. But the label that has stuck is Atari Democrats. The label is glib, but it flows from a basic truth: our concern for keeping America technologically competitive with Japan and other countries.

In other words, these were Democrats who heard pull-up-by-the-bootstraps language and didn’t immediately respond skeptically. They could support progressive efforts while still supporting the need for economic stimulation.

Tsongas was far from alone in making a case for this kind of tech-forward thinking. A few other politicians often called Atari Democrats represent a who’s who of (relatively) young Democrats in the 1980s—Gary Hart, Al Gore, Bill Bradley, and Michael Dukakis, just to name a few marquee names. The economist and modern-day liberal commentator Robert Reich, before becoming Bill Clinton’s well-regarded Labor Secretary, had gained a reputation as the guy who would help a future Atari Democrat president set the agenda. (That would eventually happen.)

So, what about the namesake? Well, Atari, then at the peak of its success, looked like a great example to emulate in this context. Owned by Warner Communications at the time, the company had introduced video games to millions of homes. And this was a company that wasn’t looking for a handout, necessarily, but one that effectively inspired the creation of an entire industry out of thin air.

An Atari factory in action.

From a public policy standpoint, Atari’s success looked incredibly appealing, something to support. If done right, the thinking went, it could inspire hundreds of companies just like it in its wake—American companies. It had already directly inspired one manufacturer that was already pretty sizable by that point—Apple Computer, whose cofounder Steve Jobs famously worked the late shift at Atari in the mid-1970s.

One could argue that there might have been a better example for the moderate Democrats to follow—Apple, Microsoft, and Commodore come to mind—but at the time the term came about, Atari was on top of the world. (As anyone who remembers this story knows, it would not stay there.)

By the 1984 election, it was clear that the goal of all the Atari Democrat chatter was to make an Atari Democrat the next president. While that wasn’t exactly the most compelling stump speech, especially given that the video game crash of 1983 centered around Atari, it nonetheless reflected a willingness to adapt to an era of politics that had started to oppose more left-leaning initiatives.

It did not happen on the first or even the second try. Honestly, it didn’t actually happen at all, unless you think Joe Biden circa 2023 is an Atari Democrat. (The case has been made.)

Tsongas, while popular, was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 1983, sidelining him at the height of his popularity and the height of the Atari Democrat movement, while Gary Hart, who saw success in the 1984 Democratic primary (minus an infamous “Where’s the Beef” mic drop), dropped out of the 1988 presidential race after details of an extramarital affair emerged. While Tsongas tried making a comeback with a 1992 presidential primary run, he ultimately was upstaged in the only election he lost in his lifetime.

But Gore, who first came to the senate in 1985 and finished third in the 1988 Democratic primaries, would eventually be the vessel into the mainstream through which many of the Atari Democrat ideals would carry. While he did not win the 2000 election and only ultimately served as vice president, his role essentially put him in the pole position of influence on Democratic technology issues.

Perhaps it’s no surprise that some of tech’s biggest mainstream wins began to emerge in the 1990s.

“Just as information spewing forth from the printing press was soon protected in democratic states by a fair and workable legal and ethical code, so, too, a new body of common law is being built to cope with the new medium of the computer network. Rather than holding back, the U.S. should lead by building the information infrastructure, essential if all Americans are to gain access to this transforming technology.”

— Al Gore, writing in his seminal article “Infrastructure for the Global Village,” one of a series of essays included in the September 1991 issue of Scientific American. Gore, famously, is derided for having claimed to have invented the internet (he didn’t), but the truth is that Gore actually played a key public policy role in helping to allow the internet to go commercial, building support for it in the halls of Congress, and leading to his spot in the Internet Hall of Fame. He developed sponsored a 1991 bill called the High-Performance Computing and Communications Act, which allocated $600 million to high-technology efforts. It ultimately helped to fund a number of technology products, the most famous of which was the Mosaic browser. (One thing you can give Gore credit for popularizing is the term “information superhighway.” While first used by Korean-American artist Nam June Paik in 1974, Gore first used it in a Congressional speech way back in 1978, well before anyone even knew what an Atari Democrat or even the internet was.)

Al Gore shows the internet to Bill Nye.

Why the concept of “Atari Democrats,” then and now, commonly gets derided

Look, in retrospect, it feels like folks like Paul Tsongas and Al Gore were actually way ahead of their time by suggesting in 1982 and 1983 that the right move to help revive the economy was to invest in technology. Certainly their argument has arguably turned into the defining one of the 21st century, even if it was ultimately Apple and Microsoft, not Atari, leading the way.

It’s arguable that Gore in particular, while he did not invent the internet, was an important champion of commercializing and expanding it, which is exactly why Gore deserves a spot on Apple’s board.

And from a job-production standpoint, tech did create a lot of great information economy jobs that pay really well compared to the more industrial jobs that they replaced. (They also did create Uber and DoorDash, but that’s besides the point.)

But it’s hard not to look at the rise of the Atari Democrats with something of a disappointing frown if you lean a bit further to the left than Paul Tsongas. The reason for that is that, while it certainly sounded like a great way to harness the energy of a surging economic engine, it also felt like an admission to many on the left that the days of government solving big economic problems had been replaced with something closer to traditional capitalism.

As Robert Lekachman, an economist who supported a more socialistic approach to distributing wealth, wrote in a 1982 op-ed piece about the phenomenon, the Atari Democrat movement looked a bit anemic in comparison to actual liberalism.

Sure it looked better than supply-side economics, but it still had its downsides, per Lekachman:

In a way, it all makes uninspiring sense. At the least, the neo-liberal agenda is preferable to supply-side nonsense or the protracted high unemployment that Feldstein and Treasury Secretary Donald Regan prescribe. Moreover, politically the neo-liberals do answer Republican challenges to define better solutions to America’s economic malaise than supply-side nostrums.

But for all its minor virtues, neo-liberalism ought not be confused with traditional, highly honorable liberal aspirations for full employment, universal health coverage, tax equity, adequate housing, urban rehabilitation, integration of minorities in-to the labor force, and mild redistribution of income.

Essentially, Atari-era politics was an inroad to watering down some of the big gains of presidents like FDR, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson.

And many might feel like that by investing in the power of technology as a job driver didn’t give enough support to the existing jobs that were already there. In fact, some later assessments of the Atari Democrats from the left, such as Lily Geismer’s Left Behind: The Democrats’ Failed Attempt to Solve Inequality, suggested that the New Democrat movement, which the Atari Democrats ultimately fell under, had some pretty significant blind spots.

As Geismer told Jacobin last year:

And some of the Atari Dems are from Massachusetts. They’re from all over, but because they’re all white men, it gives a particular gloss to their image. They got attacked a lot on that when they first formed; they actually did try to move beyond that, bringing in people of color and some women to try to diversify their image.

But they were very much the white men–dominated image. People have asked me what I was the most surprised by while working on the book. I had always seen the New Democrats as oblivious or ignorant of organized labor—as if it was just not on their radar. What I found writing this book was outright hostility to organized labor. They really tried to marginalize labor’s voice within the Democratic Party, both in terms of its electoral role and its place in terms of policy. The other critical thing about the [Democratic Leadership Council] is that oftentimes they’ve been looked at purely in terms of their political strategy, but they also have a very clear kind of ideological agenda. They were not just trying to win elections. They also wanted to change the ideological tenor of the party.

One can say that the movement successfully got Bill Clinton into office—he wasn’t really an Atari Democrat, but he checked many of the boxes of that movement—where he further weakened some of the key success stories of prior generations of Democratic leadership, like welfare.

/uploads/Atari-Landfill.jpg)

But it wasn’t like watering down the liberal movement won them fans on the right. Just check out this 1982 take on the Atari Democrat movement from libertarian commentator John Chamberlain:

But even if the Atari Democrats would get their proposed tripartite agency going without a debilitating fight, wouldn’t it be a supererogatory gesture? If the savings are there, the newer high-tech industries will be doing the borrowing anyway simply because they can pay higher interest on loans than steel or automobiles. And if the savings are not there, money shunted by government to computer companies and such would have to be manufactured by the Federal Reserve and would simply add to the inflation.

The Atari Democrats pride themselves on their long-term view. But they fail to reckon with the critics who insist that there can be no good future for any big segment of American business unless the currency can be stablished over an even longer span of time than anything the Ataris have in mind. As long as heavy government deficits are soaking up the savings of a nation, there will be little investment money available for high-tech research and development expansion no matter who does the thinking about future markets.

So this pro-business sentiment—using the power of government to help give a leg up to big business—didn’t even impress the fiscal conservatives of the world.

Policy has effects, and the effect in the case of the Atari Democrats is that it allowed us to capture the excitement of technology on the policy stage because of a handful of politicians who “got it.”

But we also weakened a lot of other things that Democrats cared about along the way.

“There are a bunch of Democrats, many of whom are my friends, who for a while thought we could maintain our society on the basis of high technology. They called themselves the Atari Democrats. You do not hear a Democrat today describing himself as an Atari Democrat. The reason is simple: Atari has moved overseas.”

— Richard L. Ottinger, a Democrat from New York, discussing the downfall of the Atari Democrat movement, in his view, during a 1984 committee meeting on the Fair Practices in Automotive Products Act, a proposed bill that aimed to give domestic vehicles more of an advantage in the market. Ottinger was ultimately half-right—while Atari Games was eventually purchased from Warner Communications by the Japan-based Namco, the more lucrative home console and home computer business was bought by the American Jack Tramiel, who previously owned Commodore.

It wasn’t all that long ago when the technology industry carried a welcome reputation in the District and on Capitol Hill. Where its potential was still fresh and unknown. The Atari Democrats clearly leaned into that mindset decades before it became a common one.

In retrospect, although it was a movement maligned both to its left and to its right, time has ultimately shown that the Atari Democrats ultimately won the argument. Tech now dominates our lives, even if Atari does not. And I will admit, you and I and everyone else have benefited from the groundwork in supporting technology that Al Gore and Gary Hart and Paul Tsongas and company put into effect in the 1980s. You can draw a straight line between their work and the modern internet.

The problem is that it left a ton of economic gaps in the process.

On the one hand, yes, the rise of technology gave us a new basis from which to build a more modern economy, and the technology jobs that replaced prior generations of work were in some cases better and more impactful on the world. But on the other hand, we now have a Big Tech problem, where companies like Meta, Alphabet, Microsoft, Amazon, and Apple are so large that you could almost think of them as quasi-governmental. And with weak labor protections, something lost during the heyday of the Atari Democrat, a lot of companies ended up laying off a lot of people like it was nothing earlier this year.

And it can be argued that, while the tech economy has led to high-paying jobs in some sectors, it ended up replacing good jobs with a lot of jobs that have fundamentally less stability—consider the labor movement’s response to the rise of Uber and Lyft, for one thing, and the direct response from Uber and Lyft.

An Atari factory, producing Pole Position arcade games.

And then there’s manufacturing—while we got a pretty decent information economy out of building an economy around Atari, we also allowed a lot of technology manufacturing to move out of the United States. We are still importing or manufacturing much of the good stuff outside of American borders, even if the companies that produce the equipment are American at heart.

Inevitably, stories like that of Gateway 2000 are common in the tech industry, where the domestic manufacturer, after a couple of tough quarters, decides to stop manufacturing computers in the United States, in hopes of saving a few bucks and keeping up with its competition. Eventually, bigger companies, like Hewlett Packard, fell into the same trap, cutting jobs instead of supporting growth.

One has to wonder if, with the rise of generative AI, we might all get outsourced by a bot. After all, these technology companies made no promises to us that they’d give us jobs if we pushed economic stimulus in their general direction, and we implemented no guardrails.

The Atari Democrats probably won more battles than they lost, but it feels like, with retrospect, it sure would have been nice had they considered all the industries that might not have had obvious ways to plug into technology. Those industries ultimately suffered, or were allowed to move elsewhere. And that’s too bad.

So, to put this all another way, Al Gore deserves his spot on the Apple board. After all, he was one of the first people to have a vision for what Apple could become in Washington.

But I hope he thinks about what he might have missed back then.

--

Congrats to Al Gore on his continued position on the Apple board. Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal!

And thanks to Remindful for sponsoring.

(By the way, Remindful is the first sponsor of ours to take advantage of our new self-serve ad system. Want to sponsor an upcoming issue of Tedium? Learn more here.)

:format(jpeg)/uploads/tedium032223.gif)

/uploads/tedium032223.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)