This Old Scandal

Why Bob Vila, perhaps the most famous handyman in history, may have set the stage for a digital era in which stars aren’t afraid to cash in on their names.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

$97.8M

The amount that Roku paid for the This Old House franchise, a popular public television staple, earlier this year as the company started building out its original programming lineup. (To give you an idea of how valuable the franchise is: Roku bought the entire Quibi show library for “significantly less” than $100 million two months prior, which means that This Old House is a more valuable asset than Quibi was, despite being a single type of show.) The purchase, which still allows the show to appear on linear television first, is interesting in the scope of the long history of the hit PBS show, given the fact that its noncommercial nature was once a major sticking point.

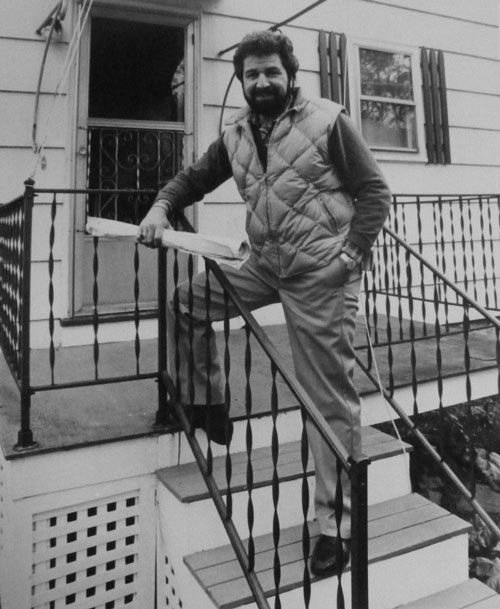

An image of Bob Vila during the early days of This Old House. (WGBH press photo)

How Bob Vila became the face of home repair

This Old House represented an interesting opening salvo in the way home renovation was presented on television.

Every season, the show would highlight an aging house, and renovate it, step by step, over the span of a number of episodes. Rather than today’s more common HGTV-driven approach of showing a “flip” over the span of an entire episode, the show focused on the process, detail by painstaking detail.

“It’s an adventure story,” producer Russell Morash stated at the time of the show’s national expansion in 1980. “We wonder what’s going to happen week to week. Will they solve this or that problem? That’s enough to keep you interested. But it ain’t hard-core how-to. No, no. For that you’ll have to turn to an encyclopedia.”

Vila stumbled into the job as a result of his home-restoration business R.J. Vila Inc., which had won an award from Better Homes and Gardens magazine for fixing up a Victorian house in Newton Center, Massachusetts. Vila and his wife, Diana Barrett, earned a profile in The Boston Globe for the project, which Vila and Barrett personally restored with an eye to keeping its classic qualities intact. (They, of course, bought the home for themselves.) This profile earned Vila the notice of the Boston-area public television WGBH, which was looking for someone to host a home-improvement show.

Vila ended up hosting that show for a full decade, with the show going national in its second year.

Morash’s approach had already drawn one of the most iconic success stories in the history of public television: Julia Child came to prominence through her WGBH-produced cooking show, codeveloped by Morash. As an educational program focused on a broad niche, This Old House used much the same framework as Child’s show The French Chef and The Victory Garden, a show about gardening that Morash also created.

Due to its status as a show on public television, the show’s on-air personalities initially went out of their way not to mention brands during the show. In one example cited by Morash in a Boston Magazine oral history from 2009, the show’s producers would actively hide the Owens Corning branding on rolls of fiberglass (even though Owens Corning was an underwriter for the show!), which led the manufacturer to change the way the rolls were branded so hiding the detail was unavoidable.

During its first decade of existence, the show, as it highlighted demolitions, touch-ups, and all the headaches that happened in-between, had Vila right at the center as the everyman who explained what was happening as it was happening—with familiar faces like construction pro Tom Silva, Richard Trethewey (the resident plumbing and HVAC expert), and master carpenter Norm Abram helping to see the renovations through to the end.

Trethewey and Abram are still with the show after all these years—and the show is still chugging along, like the homes that gained a second life from This Old House’s TLC. But Vila? Well, let’s just say things got messy.

“They came up with three concepts, but they didn’t seem to fit my stand-up character. We spent the next year working on it. I had in mind a Bob Vila character in his home life. I’m a big fan of his old show ‘This Old House,’ and his new show, ‘Home Again.’”

— Tim Allen, discussing how Bob Vila was a direct inspiration for Tim Taylor, the character he played for eight seasons on Home Improvement, in a 1991 Associated Press interview. Allen took such inspiration from Vila that Vila was a guest star on the show multiple times, with Vila appearing as Taylor’s rival. In the oral history, Vila noted that he was approached by the creators of Home Improvement, Disney, regarding whether he felt that the show would be ripping him off at all.

A YouTube clip of Bob Vila and Norm Abram on Late Night With David Letterman. Anyone getting any Tool Time vibes from this?

Why Bob Vila’s ouster from “This Old House” reflects deeper tensions around public television

In a lot of ways, the issue Vila faced was not unlike the problem that The Disney Channel’s star system was designed to anticipate: He outgrew the franchise that made him famous.

But there were bigger issues at play, issues that cut at the core of PBS’ overall mission to provide quality public programming, and issues that constantly lingered behind the scenes. As the home-improvement show became one of the most popular shows on public television, President Ronald Reagan was aggressively going after public television’s funding, and would often veto bills aimed at increasing that budget during his time in office.

Funding challenges like this, often common for public television outlets during conservative presidential administrations, created a natural tension between television created as a public service and the commercial realities of how the bills needed to be paid. So often, public broadcasting would turn to underwriting, allowing corporations to pick up the bills in a way that wasn’t directly advertising but served much the same purpose.

In the 1997 book Made Possible By …: The Death of Public Broadcasting in the United States, author James Ledbetter makes a compelling case that this kind of underwriting threatened the very mission of the public television, because of the way that financial pressures could directly or indirectly influence what gets on the air.

“Today, corporate underwriting represents more than 16 percent of PBS’ overall budget—up from 10 percent a decade go—and 27 percent of its national programming costs,” Ledbetter wrote at the time. “Though that may appear to be far from a controlling interest, there are virtually no programs on the PBS dial that are not in some way beholden to private, commercial firms.”

(These days, larger stations receive most of their funding from a combination of donations from the public and underwritten content, with digital distribution also helping to drive revenue. It was necessary: The Trump administration, like Reagan, took an aggressive stance against government funding of public television.)

The complicated funding picture of public television funding trickled down, of course, to individual shows, such as This Old House. Initially, WGBH couldn’t afford to pay the stars a ton of money. According to Boston Magazine’s oral history, Vila only made $200 per episode at the start of the series, later increasing to $800 per episode. Vila appeared in 235 episodes of the series in a 10-year period, meaning the minimum he could have made from the show was $47,000 over a decade and the maximum $188,000. As a skilled handyman and contractor, he treated the hosting gig as a side business for his contracting firm R.J. Vila Inc., but if it were his only job, he would likely be making more money with a standard white-collar desk job, even at 1988 wages.

Still, it’d be understandable if Vila saw simply promoting his local contracting business as failing to properly capitalize on his national television profile. If Vila wanted to make any serious money off his status as a home-improvement guru, he would be required to become a pitchman.

So he did—making up to $500,000 per year off of his name during the latter years of the PBS show.

Julia Child faced a similar situation of extreme fame on a public television budget, but rather than leaning on sponsorship, she sold books and videos that went deeper into the art of cooking. Vila wrote books, too, but his sponsorship approach was a faster shortcut to capitalizing on this kind of success.

Vila never hid what he was doing, and disclosed and gave approval rights to each commercial opportunity to the bosses at WGBH, but even with that in mind, his aggressive salesman approach ultimately ran head-first into the realities of the public television funding situation.

The Home Depot, already a dominant national chain in the late ’80s as well as an underwriter for This Old House, took umbrage at the fact that Vila was a commercial spokesman for a smaller competing chain called Rickel. Despite being given the OK to play the role as spokesperson for Rickel and a number of other companies, the underwriting problem led WGBH to ask Vila to drop his work as a commercial spokesperson. As you might guess from the fact that I’m writing this article, he refused to drop the source of most of his income, and he was fired.

In Boston Magazine’s oral history, Morash suggested that beyond the sponsorship issues, Vila’s approach had become too slick for the show.

“In the early days of the show, as I said again and again, the host asks the questions that the homeowner has,” Morash said. “If the host appears to know the answer, it changes the chemistry completely. As Vila matured, he became the expert. What kind of cuckoo land was that?”

Bob Vila in a commercial for Sears, which was for decades his main meal ticket.

As Vila was quick to note, the exit turned out to be the best possible thing for his career—within a year, he was the primary spokesperson for Sears’ hardware businesses (a role he held for nearly two decades), and he had his own long-running syndicated television show called Bob Vila’s Home Again.

“My departure was prompted by flaws in that system. I was caught between a rock and a hard place,” Vila said in a 1995 interview.

And This Old House survived as well, bringing on a series of new hosts, including Steve Thomas and current host Kevin O’Connor, both of whom stayed with the show longer than Vila did. There was enough room for two home-improvement shows with a relatively similar approach. Really, the only loser out of this was Rickel, whose chain was soon steamrolled by The Home Depot.

Nonetheless, Vila’s firing didn’t go over particularly well, and for years, there was lingering tension between Vila and the show he created, especially as the commercial realities of public television led This Old House in directions that seemed to directly conflict with the reasons Vila was fired.

Even while Vila was still there, the logos started to be displayed on the goods that were donated to the public television production, thanks in part to the Reagan-era austerity. (This actually caused problems for homeowners, who were found to owe taxes on the donated goods.) And WGBH later became more savvy about making money on the side from the show, including through the launch of This Old House Magazine in the mid-1990s, a title that is still published today. (Vila tried doing the same thing with a title called Bob Vila’s American Home, though that faltered in 1998; these days he runs a namesake website with a similar approach.)

WGBH’s Peter McGhee, in a 1996 Wall Street Journal article, tried making the case that it was not hypocritical for the show to make money off of side ventures in this way.

“With the show’s integrity intact, it turns out to have value in other markets,” McGhee stated.

It’s a complicated line to straddle—and it may be an even more complicated one now that Roku is in the picture—but it’s far from an uncommon one in the world of public television.

“I was at the Habitat for Humanity Awards in New York, and under my name in the brochure was This Old House. My wife asked me when I thought people would finally get it straight. They don’t have to get it straight. I own part of the franchise.”

— Vila, in a 2004 newspaper interview, discussing the fact that he was still deeply associated with the show he helped create 15 years after he left it. Despite leaving for more commercial pastures with Home Again, a show he produced until 2007, he emphasized a fairly old-school approach to home repair, rather than a more infotainment approach that more recent home-improvement shows (see Property Brothers, Fixer Upper) specialize in. He was also direct about the role his sponsors played in the show, even as he emphasized his independence. “My partners at Sears and I talk about the subject matter, and I listen to what they suggest, but there is never any pressure on me to do ‘reality’ shows,” he stated in the piece. (Vila’s relationship with Sears broke down in 2006 because everything involving Sears was starting to break down around that time.)

To be clear, I’m not trying to begrudge Bob Vila his success at all. He got into the home-repair business as an entrepreneur, not a philanthropist, and it just turned out that his entrance into a public profile came about in a medium, public television, that was rife with ethical conflicts, most of which he wasn’t responsible for and wouldn’t have faced if he was on another channel.

Just because he was on public television doesn’t mean that he automatically stopped being a businessman. In fact, his status as a businessman who could effectively educate others on camera made him even smarter about maximizing his profile.

“I am at heart a capitalist,” he stated in a 1996 Wall Street Journal article in which he discussed getting “payback” on his old stomping grounds as each tried launching magazines. “The years I hosted on PBS I compare to the years I volunteered for the Peace Corps.”

(Vila wasn’t using hyperbole there—he actually served in the Peace Corps in the early ’70s.)

The TV handyman hasn’t had a regular show on the air in a few years, but repeats spring eternal and his profile remains sizable—so much so that he’s had to deal with multiple lawsuits in recent years related to people trying to capitalize on his likeness rights.

Vila offers an interesting comparison point to today’s spate of cultural creators: When it comes down to it, Bob Vila’s situation in the late ’80s was very much like the Twitter or Instagram celebrity who built a massive platform off the back of someone else’s network, but has no way to properly monetize that from the original source. So they have to look to other places, such as crowdfunding sites like Patreon as well as commercial sponsorships, to make ends meet. Love it or hate it, that’s the commercial reality of online creation.

Vila’s “social platform” that offered limited returns just happened to be public broadcasting. But the ultimate goals were the same, even if he might have been 30 years early to the game.

Bob Vila, a handyman with presence built for TV, may have been the world’s first influence marketer.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal!

:format(jpeg)/2018/09/tedium091818.gif)

/2018/09/tedium091818.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)