By Our Powers Combined …

How the webring became the grassroots tool of choice for sharing content online in the ‘90s. The concept was social media before media was social.

Hey all, Ernie here with a refreshed piece about webrings. Sometimes it happens that you get really far on something (in my case with a piece on Linux and video game consoles, coming soon) and you want a little more time to generate the magic. That’s what happened here.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

“It is important to follow these instructions in the order given to ensure that the ring remains a ring. You may join the ring at any point but you may only join once.”

— Denis Howe, a British computer user, discussing the way that the Expanding Unidirectional Ring Of Pages, or EUROPa, works. The concept, created by Howe in 1994, is effectively the first webring, linking together a series of users on a single looping trail that can be followed all the way through. Despite the age of the concept and the lack of technology like CGI or Javascript, the webring still works today.

You know what’d be meta? A webring about Lord of the Rings.

What the heck is a webring, and how does it work?

Something about the early web completely taken advantage of now is that in the pre-Google days, search kind of sucked.

Sure, you could find websites through services like Lycos or Excite, but the engines varied wildly in quality and didn’t lend themselves to a certain kind of serendipitous discovery that is slightly easier to find online nowadays.

To put it another way, businesses were quickly trying to commercialize the web, but the individual user still had room to stand out.

And it’s with that spirit in mind that networks of users decided to self-organize their pages through lightly-organized “rings” that would lead users to pages on a similar topic. Having a link somewhere on your site that ensured users that your page was a way station in a series of pages on a similar theme.

Structurally, a webring has many parallels to the modern-day Twitter quote-tweet chain, a Russian nesting doll of sorts in which you’re encouraged to keep clicking on the tweets being quoted, with no end in sight. Depending on what you’re up to at the time, it’s a novel, entertaining, somewhat curated experience.

But while the webring in its purest form was interesting and effective, it was difficult to maintain—a problem that, in 1995, an enterprising teenager named Sage Weil attempted to solve. He expanded on the basic idea that drove Denis Howe’s EUROPa experiment.

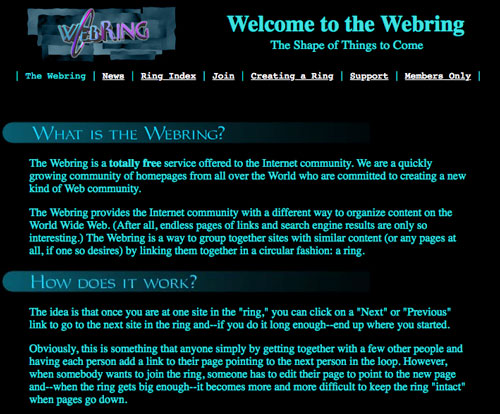

“Obviously, this is something that anyone simply by getting together with a few other people and having each person add a link to their page pointing to the next person in the loop,” Weil explained on his website in 1996. “However, when somebody wants to join the ring, someone has to edit their page to point to the new page and—when the ring gets big enough—it becomes more and more difficult to keep the ring ‘intact’ when pages go down.”

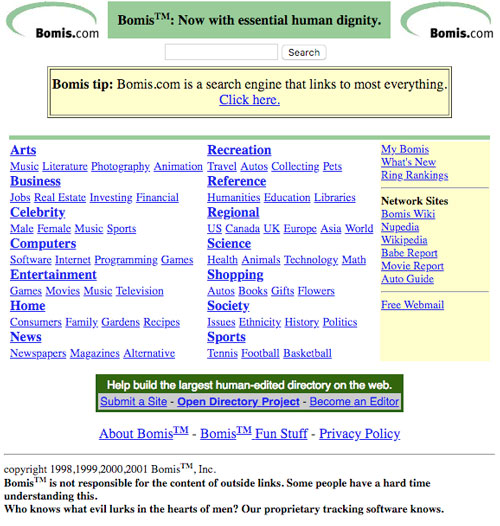

An early version of Webring.org.

Weil, still in high school at the point he launched Webring.org in 1995, made the webring easier to maintain and track through a CGI script, solving the problem of what to do when there’s a dead link.

Weil’s basic idea was trendy in the late ’90s, and became a frequent subject of newspaper articles, that frequently spoke with deep reverence of the way that the rings improved the digital experience.

“If using a search engine can be like drinking from a fire hose, Internet surfing using a Web ring is like sharing a cup of tea with a group of strangers who are batty about a favorite hobby, like collecting Australian emergency-squad insignia,” New York Times writer Tina Kelley wrote of the phenomenon in 1999.

(It also helped the concept of the webring was complex enough it lent itself to further explanation.)

And Webring.org was the most prominent of a few websites that rode this wave. Initially, the site was a ramshackle, commercial-free resource in which Weil directly shared his trials and tribulations with his audience.

Among them: Some company tried to claim it held the legal right to the name Ring, and was harassing individual webrings, though the battle was eventually resolved after a lawyer assisting Weil pointed out the number of uses of the word ring that predated the internet.

Eventually, though, the site eventually was sold off multiple times. First, a company called Starseed bought it and got Weil away from the daily grind of keeping the server online. Then, in 1998, GeoCities bought it—which made sense because webrings included many GeoCities sites—and made few changes. Then Yahoo bought GeoCities a year after that and did that thing Yahoo always does—they tried to remake the idea in its own image, ruining it in the process.

Unlike most of those situations, however, Yahoo relented and gave up ownership of the site after users complained about Yahoo’s changes.

WebRing.com only fell off the internet somewhat recently (between the time I wrote this piece and it was updated; the Internet Archive stopped tracking it in February of this year), but we had it for quite a long time—nearly a quarter century.

1996

The year that Quake was released, effectively sparking the modern trend of online multiplayer gaming. As such gaming was loosely organized with little in the way of social networks, players would organize into teams, or “clans,” to help organize deathmatches. These clans were further organized through webrings, with the largest such ring, Quake Clanring, featuring thousands of separate clans—making it one of the most elaborate uses of the webring in the early days of the internet. “The greatest thing about clans is that practically anyone can start one,” stated the pseudonymous Fargo, one of the key figures of the gaming site PlanetQuake. “The worst thing about clans, however, is that practically anyone can start one.”

Bomis.com, circa 2001. Note the fact that Wikipedia is directly adjacent to a link for a site called “Babe Report.“

How an R-rated network of webrings set the stage for modern-day Wikipedia

It’s bizarre to think about today, but the roots of one of the internet’s largest and most fundamental sites come from a website that had a reputation crass enough that The Atlantic once called Bomis.com “the Playboy of the internet, helping guys find guy stuff.”

In a 2013 interview with Wired, Wikipedia cofounder Jimmy Wales bristled against the description of his pre-Wikipedia business endeavor, which had a lad-mag sensibility and would at times feature lightly-dressed models wearing Bomis t-shirts.

“That’s a completely ridiculous description,” Wales said of the comparison. “We allowed people to categorize whatever they wanted. One very popular category turned out to be image galleries of female actresses and so forth.”

Wales was correct on this front—the site was very much angled toward the interests of its users. Being a site that, like Wikipedia, was built around user generated content—with webrings generated by users—it often reflected less the zeitgeist and more the narrow taste of the obsessive.

It was the type of site that had a politics section that was loaded with libertarian theory, because that’s what its audience was into. It had a “babe” section, as well as webrings for various female celebrities. It was known for its Star Wars links. Its news section strongly favored online sources over traditional media, and included a page called “alternative news.”

In other words, Bomis had many of the cues of modern Wikipedia without the encyclopedia to tie everything together.

That’s because, at its core, Bomis was an organizer of subcultures. Lightweight almost by the necessities of its era, it effectively combined the design sensibility of Craigslist and Yahoo into a single site, slapped on some banner ads, and made it easy to find information on topics that its audience was really interested in.

And it just turned out that one of the topics guaranteed to draw in a lot of readers was its links to adult sites, which Bomis did not shy away from, at one point even running a blog dedicated to adult content and making such content available via a membership program.

Given Wikipedia’s charitable, change-the-world goals in the modern day, Bomis has been a somewhat awkward part of Wikipedia’s history in retrospect—it probably doesn’t help that the Wikipedia page for Bomis features photos of “Bomis Babes”—but the company nonetheless was key to what Wikipedia became.

To make Wikipedia a success, Bomis—and, in a way, the webring—was sacrificed

Despite the lad-mag reputation it carried, Bomis had a higher mission at its core. It was one spelled out in a 10th-anniversary message posted on its website:

Bomis was founded in 1996. Since then it has served as a sort of laboratory for experimenting with new ideas about the modeling of information, about new systems of online community and collaboration. This laboratory has given birth to many crazy-seeming ideas. Most of these failed more or less immediately. Some of them showed promise, and then failed. A few proved to have some lasting merit. All of them provided useful insights.

One of those ideas with some lasting merit was Wikipedia, the user-editable online encyclopedia that came to life as a Bomis skunkworks project in 2001. Nupedia, the predecessor of Wikipedia, struggled to make headway because of the complex peer-review process that drove it. The internet works too fast for peer review, so they got rid of it.

Bomis, which made its money from advertising, played a fundamental role in the creation of Wikipedia, with Wales effectively using profits from the webring site to bankroll the endeavor, which initially started out as the non-user-editable Nupedia. Larry Sanger, a Bomis employee, was put in charge of Nupedia and later Wikipedia, though he had effectively left these roles before Wikipedia became a mainstream phenomenon.

But Bomis’ declining fortunes could not keep up with Wikipedia’s stunning growth, and eventually, the decision was made to take Wikipedia nonprofit, a move that, in the long run, proved brilliant.

In some ways, Wikipedia’s success as a concept benefited from the same feedback-loop dynamics that a webring does. It’s a site that rewards clicking, and becomes more valuable the further down the rabbit hole you go. It becomes like a game, almost. That, in its own way, is a dynamic that Wikipedia borrowed from Bomis and other webring-driven networks.

The only thing lost in this process of making Wikipedia a trusted source, unfortunately, is the decentralization. There’s a reason why Wikipedia is one of the largest sites on the internet, and it’s because it took the internet’s collective knowledge and put it under one roof, a culmination of the “ideas about the modeling of information” that Bomis was built upon.

In a way, it was a worthy sacrifice of the open web. What Jimmy Wales, Larry Sanger, and company had built was more fundamental than the webring.

“Google has search almost solved. But the discovery side had not been cracked. This is a tool for finding interesting pieces of content. With hundreds of millions of web pages, how do you find what is good?”

— Garrett Camp, the cofounder of StumbleUpon, in a 2007 interview with the BBC. StumbleUpon, while not a strict webring tool in that the “rings” weren’t user generated, is still worth a mention here because the design of the service was effectively an automation of the webring, encouraging serendipitous clicking by predicting what the user might want to see next and adding the introduction of data tracking. Essentially, StumbleUpon functioned as a customized webring for the end user. The service was successful enough that eBay bought it in 2007 for $75 million, but the founders bought the company back in 2009 after its traffic dropped significantly in 2008.

The webring is a mostly-forgotten part of the way that the internet worked, having been buried by ever-more-elaborate ways of exchanging links on the internet. Google is pretty smart these days, and social media makes serendipitous reading a lot easier than it once was. And the webring wasn’t built so much for blogging or the second-by-second publishing cycle of the modern web. Heck, webrings don’t even make that much sense on mobile.

But webrings were a fundamental step forward for the internet, one that inspired ever-more-sophisticated ways of sharing links. You can see its roots not just in social media, but in sites like Taboola and Outbrain.

And, as you might guess based on the time in which the webring thrived, it benefited from companies very willing to spend a lot of money on the visibility that webrings allowed.

There is no link being exchanged with this banner. I promise.

In 1998, for example, Microsoft bought the Internet Link Exchange, a banner ad network that functionally worked the same as a webring, for $265 million.

What’s interesting about the webring is that, despite the somewhat primitive nature of the technology, it inspired a lot of smart minds to eventually follow up with even more awesome stuff. And that’s not just limited to Wikipedia, either.

Sage Weil, who spent his teenage years effectively making it easier to spread information online, found even bigger success in later years, first by cofounding the well-known web hosting provider DreamHost in 1998, then by helping create the distributed storage technology Ceph, an idea innovative enough that Linux-borne software company Red Hat bought the company that created it, Inktank, for $175 million.

And Tony Hsieh, the founder and longtime CEO of the well-known shoe company Zappos and a mainstay of business culture articles over the past decade (who vacated the CEO role of that company in August), came up with the Internet Link Exchange.

For an idea that was decentralized and user-driven at its core, it sure fostered a lot of multi-millionaires.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal!

:format(jpeg)/2018/06/tedium053118.gif)

/2018/06/tedium053118.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)