TV’s Hidden Math

How the calculus of ’80s television programming lives on into the present day—and why the Disney Channel always seems to cancel shows after 65 episodes.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

1950

The year that The Cisco Kid first appeared on television. The show, filmed in color more than a decade before the practice was common on television, was one of the first successful shows to be syndicated. Its owner, Ziv Television Programs, was an offshoot of a radio syndicator who ran a similar model in the decades prior. Ziv, which shut down in 1962 after an acquisition by United Artists, was a major originator of the model. Other key shows that helped drive the success of first-run syndication in the early years of television included Soul Train, Hee Haw, and Family Feud.

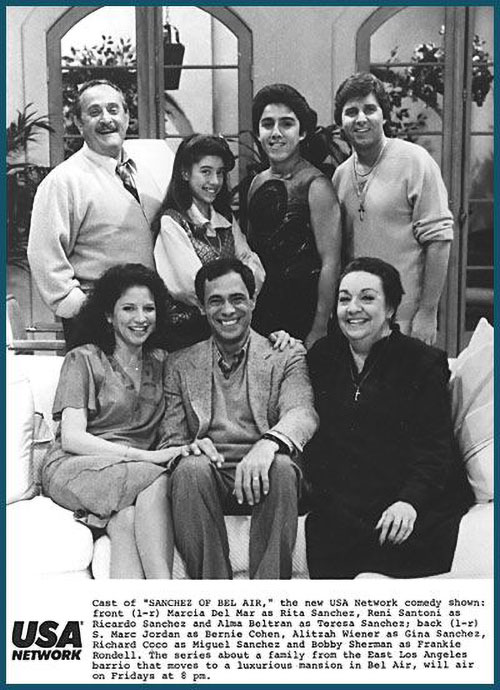

A press photo for Sanchez of Bel-Air. Yes, that’s Bobby Sherman on the top right.

The first original comedy ever produced for USA is like a bizarro-world Fresh Prince

What if I told you that the basic concept of one of the ’90s most famous shows, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, had been used just a few years earlier by an obscure show on basic cable?

And that this obscure’s show biggest legacy lay not with the stars of the show or the basic idea, but with a mathematical formula?

It’s true, friends. In 1986, the then-obscure USA Network, trying to find an audience for itself, teamed with the movie studio Paramount to create an original series called Sanchez of Bel Air, which played with a similar dynamic as Will Smith’s first major acting role. The show featured a Latino family, led by a patriarch who found sudden financial success in the fashion industry, moving to a Bel Air home—a move, full of Jeffersons-style class conflicts, that his family, which previously lived in East L.A., was admittedly less excited about.

The show aired for just 13 episodes during parts of 1986 and 1987, at a time when cable and satellite television had yet to fully take over in the United States, making it one of the most obscure sitcoms ever to air on television.

To give you an idea about the show’s obscurity: The Wikipedia pages for the two creators of the show—Becker idea man David Hackel and Boy Meets World/Girl Meets World co-creator April Kelly—do not mention this show’s existence at all.

That obscurity extends to the show’s cast. The lead character is played by Reni Santoni, who’s best known for a guest role on Seinfeld as the owner of an Italian restaurant, and the show isn’t mentioned on his Wikipedia page, either. (And he was the star!) Alma Beltran, who plays the family’s live-in grandmother with a distaste for traditional Mexican food, had a long career in Hollywood and is best known for a role on Sanford and Son. The show isn’t mentioned on her Wikipedia page, either.

One cast member that does have a Wikipedia page that mentions the show, however, is arguably its biggest name. Bobby Sherman, the dreamy pop star known for his string of hits in the ’60s and ’70s (and his retirement from pop music to become an EMT and, later, a police officer), appeared as the next-door neighbor, making the show a great point of reference for trivia nerds.

But even with the brief mention on Sherman’s Wikipedia page (which also mentions, no shit, the one-fifth scale replica of Disneyland’s Main Street that he built in his yard), this show barely even registered, even for its target audience.

(Of course, critics didn’t like it either. A 1986 New York Times roundup that savaged USA’s entire comedy lineup at the time, dismissed the show wholesale: “Everybody, including the next-door neighbor played by the former pop singer Bobby Sherman, works far too hard at being cute and ingratiating.”)

Part of the reason for this obscurity might be the sheer lack of representation of Latino characters on television at the time: As the 1994 book Handbook of Hispanic Culture in the United States: Sociology explains, most representations of Hispanic families on television in the 1970s and 1980s—if they were featured at all—were lower or middle class. For all its obscurity, Sanchez featured an upwardly mobile Hispanic family at a time when such representation did not exist in American culture. The real problem here isn’t that the fledgling USA Network made this show; it’s that ABC, NBC, and CBS didn’t.

“As of this writing, mainstream network television has no Hispanic ‘Huxtables,’ ‘Winslows,’ or even ‘Jeffersons,’” author Nicolás Kanellos wrote.

For years, the closest TV got to such a representation was a sitcom with just 13 episodes, airing on an also-ran cable network at a time when cable was still fairly uncommon.

The incredibly specific way that Sanchez of Bel Air survives into the modern day

The strange thing about Sanchez is that there is one area where the otherwise obscure show registers in a big way: The show, as one of the earliest examples of a sitcom created specifically for cable television, set a specific standard for contractual negotiations for reruns.

Here’s what happened: In the late 1980s, the Writer’s Guild of America negotiated basic cable residuals for the show that ensuring a certain level of payment based on re-airings—50 percent for the second through fifth re-airings, 6 percent for the sixth airings, 4 percent for the seventh and eighth airings, and so on, until the 13th re-airing, at which point the percentage stays at 1.5 percent. The name of the resulting contractual wrinkle? The Sanchez formula.

This is the industry standard for how residuals are calculated for basic cable television shows. A secondary formula, named for the USA-aired revival of the anthology show Alfred Hitchcock Presents, also exists for cable shows in which residuals are paid out during the initial run and twelve reruns after, but the Sanchez formula is much more common.

Could you imagine coming up with an idea for a TV show—especially, in the case of Sanchez, one focused on a minority audience that has struggled to get good representation on mainstream television in the first place—only to have the show completely fade into the ether, only to be remembered in contract negotiations?

And, not to be forgotten, to have a show with a very similar idea become fairly iconic?

Sanchez of Bel Air may not have been the greatest show of all time, but it’s a strange fate, even in the television industry.

65

The number of episodes of a television show that can air five days a week over the span of 13 weeks, or a quarter of a year. This number, for various reasons, became the standard show count for many syndicated and cable-produced series during the ’80s and ’90s. One particular company, Disney, even became infamous for its 65-episode runs of TV shows. (And yes, had it been renewed, Sanchez of Bel Air also would have received a 65-episode order.)

Mama’s Family has 130 total episodes between its network and syndication runs. Multiply 65 times two.

Why 65 episodes became the gold standard for first-run TV shows on cable and syndication

The thing that consumers need to understand about the TV industry is that it’s really a game of math—especially when it comes to first-run syndication.

Generally, the common number you hear in reference to syndication is 100, the number of episodes of a broadcast series that are considered desirable for a successful syndication run. That’s a rate that maximizes value for the production company in its initial run while ensuring enough content that the show can live forever in repetition. (Or, at least, run five days a week without a single repeat for 20 weeks.)

But when it comes to first-run syndication, the real goal is to minimize cost, because TV shows are expensive, and much of the profit is often made on the back end. This is particularly true in the case of first-run syndication, where being able to run 65 shows without a single repeat is really desirable.

Even popular shows that ran much longer in first-run syndication, like Charles in Charge, used the 65-episode rule as a benchmark. Its 126-episode count means it can run five days a week for half a year (minus four days, during which preemptions might happen anyway) without a single rerun.

Why does this specific episode count matter? It’s complicated, but the best way to explain it is this: Studios make their money on repeats.

A 1986 article on the Knight-Ridder wire service, featuring an interview with Edwin T. Vane of Westinghouse’s Group W Productions, does a great job of explaining the syndication formula, particularly when it comes to cartoons. Before the mid-’80s, Saturday mornings were considered the most attractive times to air cartoons, but the fact is, there are only so many Saturdays in a year—and kids want to be entertained seven days a week.

Advertisers saw an opportunity to maximize their money, and production shops, used to putting out seasons of 13 episodes (perhaps with six more after the fact), would simply be busier if they could ensure a show would run for 65 episodes—and by hitting a minimum number of episodes by creating series with definitive end points, you’re maximizing profits.

Furthermore, a guaranteed number of shows improved the program’s chances of success, no matter how bad it was. Compared to once-a-week network runs, Vane argued, there were simply better odds of long-term success with shows built for syndication.

“The producer can’t make any money on the first network run,” Vane explained in the story. “They may be on the network four years and still not have enough episodes to syndicate. That’s not a very attractive business.”

The success of this model in cartoons drew in larger studios—it’s no accident that Disney’s DuckTales, perhaps the most famous syndicated cartoon of all time, got its start in 1987, as this model was gaining major momentum—but also made the model attractive for sitcoms, which were both relatively inexpensive to produce and faced lower risks than they did on prime time.

And considering there were plenty of shows that had failed on major networks that could be revived in a lower-risk form—think Charles in Charge and Mama’s Family, both low-rated network shows that became syndicated hits in the late ’80s—the risks were often minimal and it offered a chance for a production company to save an investment from oblivion.

(The situation is a bit different with hour-long dramas, which tend to have bigger budgets, though Baywatch, a show NBC discarded after a single year, made it work for an impressive 10 seasons in syndication.)

Cable, in much the same way, ended up working with a very similar model. You can see this with various Nickelodeon and Disney Channel shows, where shows get repeated dozens of times.

Kim Possible was too popular for Disney Channel orthodoxy to stay in place.

Why the 65-episode model finally broke apart

If you’ve ever heard about the 65-episode rule, it’s probably because you’re a fan of the Disney Channel, which supposedly had some sort of unspoken rule about the number of episodes that can be produced of a given series.

Some of the channel’s most popular shows of all time, including Even Stevens and Lizzie McGuire, only produced 65 episodes, meaning that as the shows were at their peak and the actors were in their prime, the shows were going off the air.

As it turns out, this was less unspoken rule and more calculated business strategy. A 2003 Fortune piece explained that longtime Disney Channel president Anne Sweeney implemented the rule in the midst of the network’s late-’90s shift to original live-action content as a way to keep down costs and keep its audience in check.

As anyone who has watched Shia LaBeouf’s career can tell you, Disney Channel stars age out of the demographic pretty quickly, and the tendency for the network to develop new stars meant that, if series were kept on too long, they would get too expensive to air.

“Sweeney’s strategy, therefore, is to shoot no more than 65 episodes of any show, and to shoot them fast, before key actors outgrow their roles,” the article explains. “Once the shows are in the can, Disney can air them at a leisurely pace. More important, it can rerun the hits for years, picking up new generations of ‘tween-aged viewers and limiting the amount it pays the stars (who receive standard residuals).”

The problem with this strategy is that it eventually worked too well, and two series forced Disney to change its plans: the live-action That’s So Raven, which got a full 100-episode order, and the animated Kim Possible, whose passionate fan base was loud enough that the network broke its own rule and ordered another 22-episode season. In the latter case, it was a move the series’ creators weren’t expecting, even with the success of the 2005 TV film Kim Possible Movie: So the Drama.

“We always sort of knew after the movie’s ratings that there’d be something else with Kim, kind of,” co-creator Bob Schooley told ToonZone in 2007. “It might have been another movie, or a few more episodes. The 22 episodes kind of took us by surprise. We didn’t think it would be that big of an order.”

The pressures of youth, demographics, and ratings are still there for the Disney Channel and other networks—just ask anyone who shed a tear for Girl Meets World, taken off the air last year after 72 episodes, or fans of Nickelodeon’s teen fare, which frequently runs into similar issues—but the 65-episode rule, while it made sense according to 1980s accounting, made a lot less sense thanks to the internet, which both strengthened fan bases and made the limit seem more arbitrary than it actually was.

When we’re binging on something, we don’t want to stop.

The thing with first-run off-network shows, even if the model matters less than it once did, is that the idea still works, even in the Netflix era.

The case in point here, of course, is comedian Byron Allen, who has made a very profitable empire for himself based largely on syndication.

Byron Allen (Entertainment Studios)

If you weren’t paying attention, his purchase of The Weather Channel earlier this year might have completely come out of left field, but the truth of the matter is, he may be one of the most interesting people working in television at the moment, because he knows the fundamentals still work, even if they don’t get nearly as much attention due to streaming.

Sure, the margins are a bit lower, but Allen knows how to cut corners. Just as early television icon Danny Thomas was available to do a first-run syndicated sitcom in 1986—because, honestly, what else was he doing?—Allen was able to get Bill Bellamy and Jon Lovitz to do a sitcom a few years back called Mr. Box Office. (Also among the cast members? Gary Busey and Vivica A. Fox.)

They may not be as big of stars as they were in the ’90s, but they’re still talented and they can still do the work. Allen’s genius, as explained in this 2014 Bloomberg piece, is that he gives the shows to local networks to air for free, in exchange for the right to sell half the ads on each show—meaning that he’s giving local networks free content to advertise against, while ensuring everyone makes money off of the 30 minute time block he’s using.

Whether or not you choose a Byron Allen show over Better Call Saul is besides the point. As much of the goal of television is to entertain us, the industry is built on capitalist ideals.

And that means there will always be a Byron Allen there, ready to make some money from its mechanisms.

:format(jpeg)/2018/07/tedium072418.gif)

/2018/07/tedium072418.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)