It’s Not Delivery, It’s …

The evolution of the frozen pizza, the ideal form of sustenance for people who have an oven, a microwave, or an aversion to delivery. (Possibly all three.)

Today’s Tedium is sponsored by Intent. More from them below. ⤵️

$5.47B

The size of the frozen pizza market in the U.S. alone in 2020, according to Statista. The report noted that while DiGiorno remains the largest pizza brand in freezers—representing slightly less than a fifth of total sales—private labels take up a significant portion of the pie, above 10 percent.

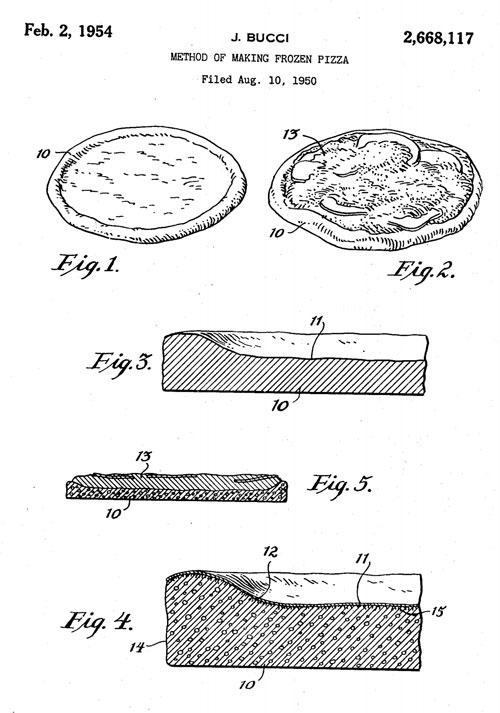

This is the most important patent in history. In. History.

The postwar pizza boom that brought us frozen pies

The idea of making ready-to-cook pizzas is very much an idea that came into its own in the years after World War II. But grocery store pizza didn’t always come in frozen form.

For example, ready-to-cook refrigerated pizzas appeared on the East Coast in 1950, with the first Roma Pizzas first showing up in Boston, then making their way down to New York City later that same year after Bostonians quickly fell in love with the refrigerated pies. The idea, per a 1950 New York Times article, was the brainchild of a guy named Leo Giuffre, whose work helped presage a multi-billion-dollar global industry.

Examples of frozen pizzas showed up around the same time, with one of the earliest patent applications being filed in 1950 and granted in 1954. The invention, by one Joseph Bucci, was intended to get around the problems with quick-freezing dough so that the pizza would have the right texture when cooked. Per the patent filing:

It has been found that even when foods of this category are quick-frozen, and then thawed out, heated and served, unwanted moisture penetrates the doughy mass and renders it soggy, and unpalatable.

It has also been found that certain. doughy constituents of foods, such for instance as the doughy portion of tomato pies as hitherto known, are irregular in consistency and appearance. Thus, for instance, according to present-day practice in making tomato pies, the dough is laid in a pan, and holes are punched in the dough to prevent air bubbles from forming during the rising and baking process. As a result, the dough is irregular in consistency, frequently gummy in some spots: and hard in other spots. In addition, the sauce which is poured over the: dough often penetrates through the punched-out portions and burns against the pan.

One object of my invention therefore, is to provide a frozen food having a doughy constituent adjacent a constituent which is of a moist or liquid consistency when at room temperature, said frozen food being so constituted that unwanted moisture may not penetrate said doughy constituent, regardless of the temperature of the food.

Bucci and Giuffre, however, weren’t the only ones getting in on the sudden demand for easy-to-make pizza at home. A Massachusetts paper had ads for frozen pizza in the early months of 1950, and in Akron, Ohio in 1952, a man named Jack DeLuca took advantage of a summer break in for restaurants in the city to come up with his own line of frozen pizzas, which became popular enough that his pizzas were in 300 shops by the end of that year.

Perhaps the real ground zero of the frozen pizza, however, might be the Chicago area, where a gigging musician named Emil De Salvi came up with Pizza-Fro, a brand of frozen pizza in 1951, and the pizzas had made it to neighboring states in the midwest in the ensuing years. Per one 1954 Chicago Tribune report, De Salvi had sold 5 million pizzas in a two-year period. Not that the data point was cheered on.

“This statistic, of course, is as loathsome as a Liberace joke,” columnist Thomas Morrow wrote. “It gives a man an uneasy stomach to think of these 5 million blobs of dough splattered over the landscape.”

Of course, the main turning point for frozen pizza came when the phenomenon went national—and a Minnesota woman named Rose Totino is widely credited for that success. Having first experienced pizza for the first time when visiting friends in Pennsylvania, she often made it for her friends, according to a 1994 Minnesota Star-Tribune obit. This eventually led Totino to launch an Italian restaurant with her husband Jim, and by 1962, the couple had started making frozen pizzas themselves.

Soon enough, their pizza brand went national, becoming the top-selling brand of frozen pizza in many of the markets where it was located. Eventually, Pillsbury bought the company out in 1975—with Rose Totino successfully convincing the grocery giant to pay $20 million, instead of the $15 million they originally offered.

It was Pillsbury’s first foray in the frozen food aisle—a place where many mealtime battles would be fought in the ensuing years. Frozen pizza was just too hard a market to pass up.

Sponsored By Intent

Apps and MVPs forged in flames

Intent has developed more than 160 apps, over 50 MVPs, and has been a Think Partner to Oura, Block, Keeps, iHeartRadio, HQ Trivia, and many more startups and scaleups. Some of them were backed by tier-one VCs, such as a16z, FirstMinute Capital, Lerer Hippeau and Canvas Ventures for example.

We have also worked with Enterprise Partners like Jeep, Maserati, McIntosh, Sonus Faber, P&G and Coty.

One of the most important things about our work is that we support the companies from ideation through product iterations to launch and even offer growth as a service after that. We do everything we can to help you succeed. As you've maybe noticed, we neither treat nor call our customers just customers. For us, they are Partners, and we take ownership and full responsibility for the projects we've been entrusted with. We don't just act. We think with our Partners and discuss the best solutions.

Our approach came from that intent began as a startup 12 years ago. We've learned the hard way, and now we thrive thanks to that. We take full ownership and responsibility. We walk the extra mile for you because not so long ago, our survival depended on that. Try us.

5,600

The number of comments that the USDA received in 1973, after it attempted to set a requirement for the amount of cheese a frozen meat pizza could have. It wanted to set the standard at 12 percent cheese, but a lot of people complained about it, so it left well enough alone. But the dairy industry kept trying, though the public kept complaining. In 1986, the National Milk Producers Federation, which would clearly benefit from more cheese and fewer fillers on the pie, had this to say about the matter: “In the absence of revised standards, USDA continues to permit manufacturers of frozen meat-topped pizza to delude the consuming public.” Political pizza fights are hardcore, guys.

Hi DiGiorno, if you’re reading this I would like you to know that I want you to tweet out my article about frozen pizza, thanks. (Liza Lagman Sperl/Flickr)

Five key turning points in the frozen pizza aisle

- “In strictly frozen-pizza terms, the year 1995 was every bit as momentous as 1066 or 1492,” The New York Times wrote in 2004. See, ’95 was the year that Kraft launched the DiGiorno Pizza, which had a real trump card for grocery store pizza: It had a rising crust. DiGiorno helped reshape the pizza industry by adding a touch of innovation to a genre of food that had been long outplayed by massive pizza chains started by men who owned Detroit sports teams.

- Minnesota plays a major role in frozen pizza history. Pizza Rolls, which are manufactured under the Totino’s brand name today, came to life in the 1950s thanks to Jeno Paulucci, a Duluth businessman who used the machine he invented to make egg rolls to put pizza stuff in those rolls instead. His company sold to Pillsbury in the 1980s for $140 million.

- Also a key Minnesota pizza success story is Schwan’s, which is best known for selling frozen foods via delivery truck, but also created a popular pizza brand of its own in 1976, when it launched the Red Baron line of pizzas. It was one of the defining pizza brands for decades and a major part of Schwan’s success.

- “When pizza’s on a bagel, you can eat pizza anytime,” the jingle goes. The guys who came up with that idea—Florida businessmen Bob Mosher and Stan Garczynski—quickly sold the product, invented in 1985, to the Canadian beer company LaBatt, only for the Heinz to purchase it in 1991. To this day, Bagel Bites are made in Fort Myers, Florida, the place where the unusual foodstuff got its start 33 years ago.

- The Hot Pocket, of course, came to life in the 1980s, when Iranian-born businessmen Paul and David Merage moved from making Belgian waffles into handheld calzones. I wrote a piece about their lives a couple of years ago.

70%

The estimated percentage of pizzas sold in schools that are produced by Schwan, a company with $3 billion in annual sales, according to a 2011 press release published by the company. The firm, as noted in a 2011 BusinessWeek article, was a key voice in getting the USDA to back down on a rule change pushed by former First Lady Michelle Obama that would have changed the way that tomato paste was measured against school nutrition requirements. Two tablespoons of tomato paste is considered the same as a half-cup of vegetables, per federal regulations.

If this material didn’t exist, Elon Musk would have had to invent it.

Why all the frozen stuff you microwave—including pizzas—has packaging covered in metal and plastic

The secret sauce of frozen pizza—and a lot of other frozen foods—isn’t really a sauce at all.

Instead, it’s plastic. Gray, shiny plastic, mixed with aluminum powder and placed on paperboard, is the thing that makes microwave pizza somewhat crispy instead of a New Miserable Experience.

That wasn’t the first invention that promised crispiness, however. The microwave susceptor, the gray plastic surface used in many kinds of microwaveable foods. The technology was invented by Pillsbury in the 1970s—around the time the company acquired Totino’s—but didn’t find success on the market until the 1980s. In the patent filing granted to Pillsbury, pizza was used as an example of a type of food that benefited from this metallic plastic film layer.

While other forms of packaging had been used to heat food in the past—check out this 1954 patent from Raytheon, a company better known as a major U.S. defense contractor—Pillsbury’s system was different, it said, as it prevented food from getting soggy.

The benefit of a suceptor is that it takes the radiation hitting the packaging and turns it into a tiny oven that helps make the food crisp. And unlike most other technology of its kind, it could be thrown away after you were done eating lunch.

“By contrast with the prior art, one major goal of the present invention is to find a way to provide an inexpensive and disposable microwave food heating container or package useful for shipping, heating and when desired to hold food as it is being eaten as well as to provide an improved method of distributing and heating foods with microwave energy,” the Pillsbury patent, granted in 1980, states.

Hot Pockets would not reach their full potential without microwave susceptors. (vandys/Flickr)

The susceptor technology, originally designed for the company’s frozen pizzas, quickly became a key element of microwaving anything with bread, with Hot Pockets being perhaps the best-known product to use them. Around 1985, Pillsbury sold retailers on the idea, and soon enough it was everywhere—which helped greatly diversify the number of processed foods being sold in the frozen aisle.

The metal-plus-plastic-plus-paper became such a key part of our microwave experience that it was sold on its own in infomercials. Cathy Mitchell, an iconic As Seen on TV infomercial host, even did a full-hour cooking guide based around Microcrisp, which was literally sold with every bread-based frozen food you could find in stores.

You may hate the nature of processed foods, but the fact of the matter is, for better or worse, the microwave susceptor has done more to change the way we cook foods than any other piece of technology in the last 40 years … with, of course, the exception of the Instant Pot.

And we have frozen pizza to thank for that innovation.

The frozen pizza, an undeniably cheap form of sustenance that is somewhere between ramen and frozen burritos on the Broke College Student Food Pyramid, is a product that makes for a great cultural export.

Heck, some countries have made it their own. According to Atlas Obscura, Norway has gained a deep appreciation for a specific brand of frozen pizza, Grandiosa, which represents more than half of the 47 million frozen pizzas eaten in the country during the twelve-month period in which the earth orbits around the sun.

But given that frozen pizza is basically the world’s greatest example of frozen food’s tendency to bend expectations for what we consider food, it only makes sense that frozen pizzas have continued to evolve in new and unusual ways.

Currently, the fastest-growing brand of frozen pizza in the United States is something called Caulipower, which features a gluten-free crust made of broccoli, obviously. No, I’m lying; it’s Brussels sprouts. No, I’m lying again—it’s cauliflower. (Why did it take me three tries to write the right veggie? Am I a cauliflower skeptic?)

Bacon and pepperoni, together at last. (theimpulsivebuy/Flickr)

Given that pizzas have already been wrapped in egg rolls, thrown on bagels, wrapped in bread, and used to flavor ice cream, I’m sure that we’ve not seen the last of frozen pizza innovation.

In fact, someone is probably out there creating a vending machine that dishes out fully cooked pizza slices on demand. (I just guessed that someone was making this, and lo and behold, there was a link!)

I know that Carl Sagan sent that golden record into space to let the aliens know what we were like and that we have good taste in music, but what he should have done was sent a frozen pizza into space. It says more about us, as a culture, than pretty much anything else we’ve ever created—food or otherwise.

All hail the frozen pizza.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal! And thanks again to Intent for sponsoring.

:format(jpeg)/2018/04/tedium041718.gif)

/2018/04/tedium041718.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)