Sounding Board

After pissing off half the internet with our list on faded graphics formats, we’re doing the same thing with outdated audio formats. We’re fearing the worst.

⬇️ Be sure to check out today’s sponsor, Revival, below. ⬇️

Sponsored By Revival

Ever try to buy a nice rug online? The process has traditonally been a bit of a pain, but in 2017, Revival stepped in to give floors the world over a makeover. With more than 4,000 rugs from 3 different countries—produced sustainably, with fair wages—you can tie the room together while keeping your ethical compass in check. Learn more, and check out a few cool-looking rugs, over this way.

1. 8-Bit Sampled Voice

File type: Uncompressed audio, audio sampling

Most common file extension: 8SVX

The thing that’s really interesting about audio formats compared to image formats is that a lot of the old ones—WAV, AU, AIFF—have maintained some consistent form of use over the past few decades (despite, as in the case of AU, the format originating with the Sun SPARCstation and the NeXT Cube, two machines that have been resigned to the history books).

Despite that, these formats are each roughly 30 years old in age; this format, developed by Electronic Arts in 1985, is a few years older, reflecting how far ahead of the rest of the market Commodore was as far as audio goes. 8SVX is a derivative of the IFF format that Electronic Arts used for its DeluxePaint program.

2. Sound Interface Device file

File type: Musical notation

Most common file extension: SID

“Are you keeping up with the Commodore? Because the Commodore is keeping up with you,” says the jingle, which (apologies to “Apple II Forever”) is the height of 80s computer commercial jingles.

But the Commodore 64 had something to cheer about with its Sound Interface Device chip, which was one of the first specialized audio chips in a modern computer, and was able to create sounds well past many video game consoles of its era. The SID files that could be extracted from many C64 applications—something first done by Amiga programmers in the early 1990s—are obviously relics of their time, but very much reflect the state of their era-appropriate art.

3. Creative Voice file

File type: Audio sampling

Most common file extension: VOC

This relic of the Sound Blaster era of computer audio was actually developed by Creative, the company that made the Sound Blaster, and was often used for voice samples in many games of the era that supported the hugely popular sound card. (Perhaps its best-known use case is Duke Nukem 3D.)

Despite the fact that this format is more than 30 years old and was generally only used for early PC games, I was able to download some files linked by the Archive Team in this wiki article, and they played perfectly using VLC. Another VOC format, produced by RCA, was used in that company’s digital voice recorders—it too, is long forgotten.

4. id Music File

File type: Musical notation, FM synthesis

Most common file extension: IMF

A similar format to VOC, although not used for the same types of use cases, is the IMF audio format, developed by id Software for use in games like Wolfenstein 3D and Commander Keen.

This format, which essentially pushes raw data to the 8-bit Adlib sound card and its successors, was one of many proprietary audio formats developed by the producers of video games, and is a key subject of the Video Game Music Preservation Foundation’s work.

5. Adaptive Transform Acoustic Coding (ATRAC)

File type: Lossy compression, proprietary

Most common file extension: AA3

This is a file format with a basis in a noble device’s history, but was so tied to the company that made said device that its proprietary nature completely got in the way of its commercial use case.

The device was the Sony MiniDisc, perhaps the most-loved proprietary cult device of all time, and ATRAC was the compression format that made it possible for those discs to reach near-CD quality in a small amount of space. The problem was, the market had pushed into the direction of the MP3, leaving ATRAC in the dust, despite Sony’s many attempts to push it onto later devices, such as the PlayStation Portable and PlayStation 3. (Larding the format up with digital rights management at some point really didn’t help things, either.)

The company killed the format once and for all in 2009, not long after the company decided to end its DRM-oriented Sony Connect Music Store.

/uploads/Wavelab.gif)

6. Original Sound Quality

File type: Lossless compression, proprietary

Most common file extension: OSQ

As you may have learned from ATRAC just a second ago, building a proprietary audio format that only your company uses, and nobody else, is a great shortcut to the historical trash bin.

But the German audio company Steinberg, which has been building software and hardware production tools since the days of the Commodore 64, at least had a good reason for it. The company created its lossless OSQ format in 2002, which was tied to its WaveLab software, a common tool for mastering audio. While able to compress a full-fat audio file by half, that level of compression is not very comparable to the MP3, meaning that the format is better for archival than common use. Better, more open formats soon emerged, and while WaveLab still technically supports the format, it only does so in a read-only way, ensuring that those who use it are likely to upgrade to a more modern format like FLAC.

(Steinberg’s VST audio plug-in interface standard is a much more successful and common format, in part because Steinberg widely shared it with others.)

/uploads/DAB-Radio.jpg)

7. MPEG-1 Audio Layer II

File type: Lossy compression

Most common file extension: MP2

This is the one on this list that is most likely tempting fate—this has “the TIFF of this list” written all over it.

That’s because MP2, while far less common than its later audio cousin MP3, has traditionally been heavily used in a specialized broadcasting context for many years, though the push to digital radio is finally starting to change that, as higher-quality digital broadcasts are starting to highlight the MP2’s fidelity weaknesses.

However, the push to digital radio is also allowing the format to outstay its welcome in some parts of the world—the original Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB) format is still based on MP2, and while DAB+ uses the objectively better AAC format that’s common on iPhones, a lot of countries (most notably the UK) are still grandfathered into DAB. So given all that, why include it on the list? Simply put, it’s very uncommon to see an MP2 in the wild, while MP3, for all its modern-day limitations, is everywhere.

8. Mobile XMF (Beatnik)

File type: Musical notation, polyphonic, ringtone

Most common file extension: XMF

While the XMF format is technically not dead and is still being produced today as an open standard under the wing of the MIDI Association, the format had a major degree of mainstream pop culture success in the early 2000s, thanks to its use by Beatnik as a way to produce polyphonic ringtones.

Beatnik, as you’ll recall, was Thomas Dolby’s audio company, which previously produced a format called RMF that was used with the WebTV set-top device. (RMF is even more dead than XMF in this context.)

XMF’s use in ringtones was a huge success for a time, but as phones increasingly became able to produce high-quality audio on their own with no assistance, the specialized ringtone format faded away.

9. RealAudio

File type: Lossy compression, streaming audio, proprietary

Most common file extension: RA, RAM

The RealAudio format, no matter your thoughts about it and its capability to work with extremely minimal sound quality, has the notable distinction of being the first audio format many people heard over the internet (or second, after MIDI), in quality levels far below that of a traditional telephone call—after all, if it was traveling over your phone line with other stuff, there simply wasn’t as much room for actual good audio.

Nonetheless, RealAudio was nice because it eventually scaled up to more normal levels of audio quality … though it ran into the fast-moving blades of Microsoft, which eventually used its might to sour Real’s position in the marketplace, leading Real to eventually win a large settlement that allowed it to survive as a company for decades despite being completely forgotten about in its home market. And the file format that killed it? Well …

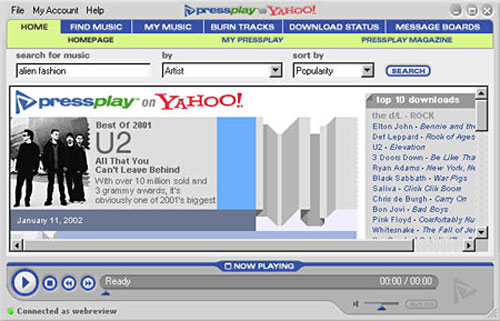

An example of the Pressplay service. (via OpenP2P)

10. Windows Media Audio (WMA)

File type: Lossy compression, proprietary

Most common file extension: WMA

This format deserves the honor of being the first audio format most people ran into with digital rights management already baked in.

While RealNetworks’ tie to MusicNet also had DRM baked in, Microsoft tended to have the leverage thanks to its ownership of Windows, and WMA was used in numerous successors to its early DRM music store Pressplay, including Napster and the Zune Music Store.

But as the music industry moved away from DRM-laden music stores and towards audio files reliant on open standards, WMA’s value proposition began to fade; at one point, Microsoft even released a version of Windows 10 that actually disabled the DRM’ed files from being played anymore. If that doesn’t describe an “audio file format that didn’t make it,” I can’t tell you what does.

You know an audio format that you might think would be on this list, but very much isn’t? Ogg Vorbis.

Released in 2000 under an open-source license, it was a seen early in its life as essentially an exotic alternative to the MP3 file, produced with open standards and without licensing fees, that could create audio files of a quality level similar to or slightly above MP3, while creating a smaller file as a result.

In a way, it seemed destined to live in obscurity, because who uses an .ogg file these days, anyway, right? Well, there’s one key user that, if nobody else used this format, would ensure that it could never be included on this list: Spotify.

Spotify has been using the Ogg Vorbis format since its start, and as a result, hundreds of millions of people use this format every single day without even realizing it. Sure, it has DRM on it, which might dampen its open-standard status, but it’s nonetheless a huge win for what some might see as an also-ran audio format that it takes on such a center-stage cultural role.

So know that, next time you play a song on Spotify, you’re listening to the way that Ogg Vorbis secretly won the war with the MP3 without the mainstream consumer even realizing it.

--

Apologies if this one upset you. Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal!

And thanks again to Revival for sponsoring.

:format(jpeg)/uploads/tedium012121-1.gif)

/uploads/tedium012121-1.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)