Corporate Casserole

Pondering Thanksgiving through an exceedingly corporate lens. Some of the holiday’s most important elements were brought to you by marketing and lobbying.

Today’s GIF comes from an actual Campbell’s commercial in which an evergreen tree grabs a bite of green bean casserole from a windowsill. I’m not making this up. Watch the commercial; it makes a strong case for why trees shouldn’t be given spoons.

Need some sharp blades in your life? Be sure to check out our review of the Imarku knife blade set, which you can check out over here. No matter the season—and whether you’re an experienced cook or barely know what you’re doing—learn about some sharp blades from a dull guy.

“We could hardly wait until the meat was carved and offered to us. Brunswick Stew came on, hearty and fiery. But the dish we fell madly in love with was a simple casserole of green beans with an intriguing topping.”

— Associated Press food editor Cecily Brownstone, writing in a 1955 article that introduced the world to the modern form of the green bean casserole, as presented to her by the Snivleys, a Florida couple. Interestingly, the article spends time discussing the fact that the dish was successfully tested with the Iranian Shah, Mohammed Reza Pahlevi, and his wife, Queen Soraya. The couple found itself serving the couple unexpectedly, having had to clear out an entire room minus one small table, for the Shah and the queen. May and her mother-in-law made the food, while the husband, John, played butler—and reportedly lost his cool when the queen kept asking what was in every dish. “Listen lady,” he reportedly said. “It’s just beans and stuff.” This story, placed with the help of Campbell’s, helped cement a Thanksgiving legend.

This pie, as we know it today, is a corporate invention. (Gloria Cabada-Leman/Flickr)

Five aspects of Thanksgiving brought to life thanks to the power of corporate marketing schemes

- The Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, as you might guess, is sponsored by … nobody. (Kidding!) But the event, in all seriousness, came about as a parade spearheaded by a department store in nearby Newark, New Jersey. The Bamberger’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, a promotional event for the department store, was transferred into NYC proper in 1924 under the Macy’s banner, and the two parades took place concurrently for decades. (Bamberger’s, which was acquired by Macy’s in 1929, also plays a key part in New York and New Jersey broadcast lore, with both WOR radio and its namesake television station launching at the company, with the former created basically to promote sales of the store’s radio receivers.)

- The roots of the presidential turkey pardon, legitimately a product of the Iran-Contra crisis (really), came about in part because of a conflict between Harry S. Truman and the Poultry and Egg National Board, which had a beef with Truman after he attempted to convince the public to go meatless as part of the postwar aid effort. This has led the turkey industry, since 1947, to drop off a turkey at the White House. The idea of “pardoning” the turkey came later, thanks to a joke made by Ronald Reagan during a fraught session with reporters. These days, the National Turkey Federation, a major supporter of the turkey industry, is the primary driver of the event.

- Thanksgiving football games, which generally feature the Detroit Lions and Dallas Cowboys, started out in each case in an attempt to build momentum around each team—the Lions starting in the 1930s, and the Cowboys starting in the 1960s. While football’s tie to Thanksgiving predates both teams, the Lions and Cowboys were most effective, thanks to savvy moves by each team. The Lions took advantage of the fact that its owner at the time also owned the local NBC radio affiliate, and was able to get the network to broadcast the games nationally; the Cowboys, meanwhile, convinced the NFL to let them put on a second Thanksgiving game as the team, still relatively new, was looking to market itself, and took the game despite only being promised payment from the league if they hit a certain level of attendance size—a gamble that appears to have worked based on the number of Cowboys fans there are outside of Texas.

- Pecan pie, the best kind of pie eaten at Thanksgiving, was given a major leg up in the 1930s after the makers of Karo corn syrup announced a new recipe that used the syrup. Invented by the wife of a company salesman, the recipe soon became a favorite of many holiday celebrations (and later, an opportunity for corporate bastardization), but it also highlighted the way the makers of Karo had brilliantly moved past a period in which the syrup was marketed as an anti-depression elixir, a claim banned by the Food and Drug Act. The secret? They started selling Karo cookbooks instead.

- Giving employees the damn day off to be with their families, believe it or not, is also seen as a savvy marketing play. In recent years, Thanksgiving creep (or “Black Thursday,” as some have unfortunately called it) has increasingly led to many retailers, looking to goose up their bottom lines, to get their workers to come in even on Turkey Day. But after backlash ensued, some retailers made a point of working against this trend, and it actually proved a savvy play for retailers, who noticed going against the broader trend made them look better to consumers.

1913

The year canned cranberry sauce first went on sale. While cranberries were most definitively a part of the legend dating all the way back to the meals that Pilgrims and the Wampanoag tribe ate together at the Plymouth Plantation, the concept took a while to solidify into its most prominent canned form. Fascinatingly, there is a manufacturing reason behind the blob of gelatinous cranberry: The fruit has a limited harvest season, in late fall, and canning helped extend the shelf life of cranberries. Other manufacturing quirks: Cranberries are generally harvested using a “wet” process, in which a cranberry bog is flooded, separating the fruit from the plants without a lot of hand picking, and the infamous “log” of cranberry sauce, dating to the 1940s, came to being as a result of an effort to find a use for lower quality cranberries.

How the modern form of Thanksgiving came to life thanks to the influence of a magazine editor

As the United States was deep in the throes of a civil war, a decades-long campaign by a prominent magazine editor and author to take the roots of the formative days American colonialism and turn them into a moment of thanks and reflection had finally won over the guy in charge.

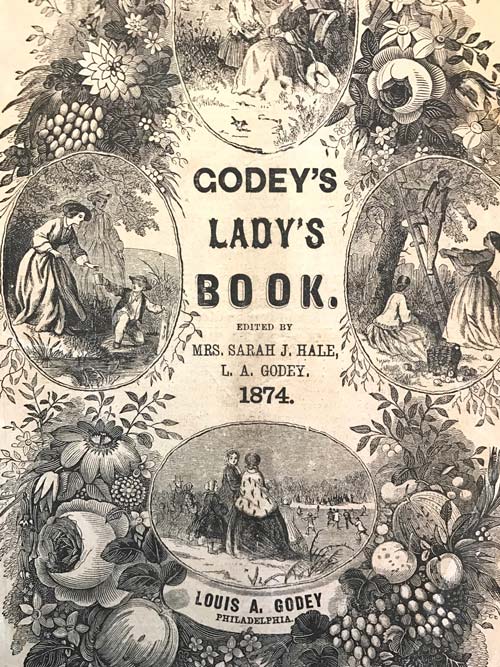

In 1863, Abraham Lincoln heard the persistent drumbeat of Sarah Josepha Hale, whose influence on American culture came in no small part due to her work on Godey’s Lady’s Book, a 19th-century publication whose reputation was hard to miss. Hale, who is otherwise legendary for her authorship of “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” used her editorship in the magazine to pitch, among other things, the value of a Thanksgiving holiday. That simple, if oft-repeated, wish helped create one of the key pieces of Americana.

And when I say oft-repeated, I mean it. She literally wrote about it dozens of times over a period of many decades, with her desire to see the holiday growing more passionate over time. She first called on governors to support the concept at a state level, then eventually taking her push national. One sample, from an 1857 editorial:

We hope the Governors will unite on November 26th, the last Thursday in the month. Then the war of politics will be over for the year; and all elections, State and National, will be closed; the harvests of the country gathered in; the preparations for winter made; and the crowning glory of all the blessings God has, during the year, bestowed on our great nation would be the union of all our States and Territories in a day of National Thanksgiving. The peoples of the Old World would thus be taught that freedom from man’s tyranny brings us nearer to God—that, while rejecting earthly lords, we willingly acknowledge our dependence on the Lord of heaven and earth.

Her lobbying from her column space helped to turn the event from a purely regional phenomenon tied to New England, one that had only briefly been nodded to on a national scale by George Washington nearly a century earlier, into a yearly event intended to tie the nation together. And while different New England states often had their own days, Hale made the push for one consistent date to rule them all. It took her more than 30 years of persistent editorials to finally, finally get a president to agree to take the whole idea national—this was not a viral campaign, this was the life’s work of one woman.

Hale has often been compared to Martha Stewart and Opera Winfrey in modern-day retellings of this story, which makes sense, as she effectively spearheaded many of the traditions that we now associate with the holiday—including, most notably, the consumption of turkey and pumpkin pie.

Some of Hale’s earliest writings about Thanksgiving made the case about the importance of pumpkin pie to the Thanksgiving meal, despite sweet pumpkin pie custard in a crust not becoming the best-known vessel for pumpkin until centuries later. (It’s likely pumpkins were used as a foodstuff in the pilgrims’ time, but not in pie form.) In her 1827 book Northwood, she wrote prominently of Thanksgiving dinner, putting pumpkin pie at the center of the tradition.

“There was a huge plum pudding, custards and pies of every name and description ever known in Yankee land; yet the pumpkin pie occupied the most distinguished niche,” she wrote.

Hale knew the value of her words—and had limits on when and how she would use them. She was, notably, an opponent of women’s suffrage, ensuring that the magazine would remain a strongly traditionalist voice, but she also was a strong patriot and knew the kind of influence the magazine, with its circulation of 150,000 at a time before the mail system was even fully baked, could carry.

As JSTOR Daily noted in 2017, the magazine tried, in its own subtle way, to fight the Civil War.

“By invoking motherhood and domesticity, Hale made a sustained argument for national unity,” JSTOR’s Erin Blakemore wrote. “She masked her worries about a potential war in stories that exalted how women could influence the actions of men from the sweet domesticity of their own homes.”

In this light, her support of Thanksgiving was a subtle political play—and that play had an effect that went far beyond the magazine’s own legacy.

Thanksgiving is treated as a day of togetherness, one that is all about the people in the room, some of who traveled long distances to get there. It’s rooted in an idea that giving thanks should be about more than what’s in our pockets. But in its own weird way, its roots represent a series of successful marketing campaigns—the idea of a magazine editor, just as green bean casserole came to life thanks to a well-placed article by a newspaper editor with the support of a company that sold a lot of canned goods.

Corn is one of the few parts of modern Thanksgiving that has legitimate roots dating back 400 years, but a company that made a corn byproduct originally sold as an anti-depression medicine turned it into the key ingredient of a modern day variant of pie.

And despite evidence that the Pilgrims ate deer rather than turkey, we gobble up the latter while the former isn’t really given a second thought.

Our holidays rely on a strong degree of myth-making, and it’s easier to make a myth when you have an influential voice. A company that sells millions of cans of soup each year is likely to have more influence over a holiday than a word-of-mouth campaign over many years.

This isn’t to say there isn’t value to what was created, or that it’s sullied because of this. But the thing about our cultural touchstones is that they’re never the result of one big thing. Instead, a lot of small things—football, corn syrup, turducken, ongoing marketing campaigns supported by the president—come together to create a mythology around a single day.

We need those myths, but we don’t need to think about where they came from every five minutes.

--

Find this one a fascinating read? Share it with a pal! And be sure to check out our imarku knife review from earlier this year. The chef in your life might just need a new blade.

:format(jpeg)/uploads/tedium112018.gif)

/uploads/tedium112018.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)