One Frame At A Time

A long time ago in an encoding standard not so far away, an early 'net user tried to remake “Star Wars” in ASCII art form. He got further than you’d guess.

Hey guys, Ernie here with a piece by Andrew Egan that discusses perhaps the most obsessive response to a movie phenomenon that drives a lot of obsessives. That’s right, we’re talking about a Star Wars fan remake. (No, not that one.) Read on:

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

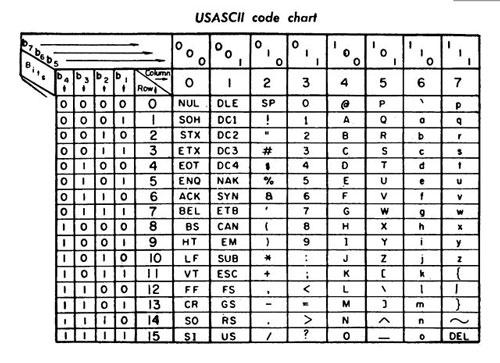

128

The number of characters in the American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII, pronounced “ass-kee”). Adopted by the US government in 1968 by the Johnson administration, ASCII quickly became the standard encoding for text files between computers.

A portion of the ASCII code chart. The emoji came later. (Wikimedia Commons)

128 characters and the man that gave us the backslash

The American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) is so basic that it’s overlooked. Put simply, it’s how you’re able to read this now. Well… kind of.

In the 1960’s, computer scientists had something of standardization problem. They needed text files between computers to understand all the characters within that file. Numbers are easy, ten digits and a few operational characters. Text means language and language is nuanced.

ASCII was the answer. Developed by a committee lead by Bob Bemer, a Pennsylvania-born computer scientist that proposed the idea, ASCII was a proposed standard for alphanumeric characters built into computers. It was a neat idea that basically became law when the US government announced it would only buy computers that complied with ASCII. In addition to proposing the standard, Bemer also introduced the backslash, which has become a staple in a number of programming languages.

Bemer wanted people to send text to one another. But like any great innovation, ASCII gave a certain kind of artist a new tool to create.

“A friend of mine in the UK sent me an email one day containing a joke. The idea was to size your window around the first picture in the joke then hit the pagedown key to display the next picture and so on. The result was a crude (in more ways that one) animation. I tried a few experiments to see how far the idea could be taken.”

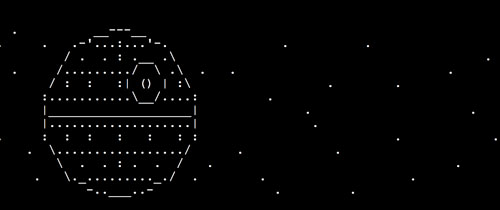

— One of many answers in the Frequently Asked Questions section of Star Wars: The ASCIIMATION. Run by Simon Jansen, the site features nearly the first 20 minutes of of Star Wars: A New Hope in ASCII animation.

Nothing new, but entirely different

As ASCII became standard, people used it to create their own art. Some of the earliest examples come courtesy of email.

In a delightful piece on the nuances of ASCII art, David Cassel notes that some of the earliest examples came from email signatures. “People labored over their ‘signature’ files,” Cassel writes. “Trying to make the end of their messages provide their contact information with a little extra pizzazz.”

And the results are pretty great.

Still, this was just a step. A single frame on the way to something truly spectacular. ASCII would find its way into mainstream pop culture and even have practical use with tools like ditaa, which converts ASCII diagrams into slick graphics. In 1997, however, a New Zealander would embark on a journey that would consume 18 years and lead to one of the greatest triumphs in ASCII art.

”Why (oh God, why)? Well, it seemed like a good idea at the time.”

— Simon Jansen’s explanation for why he started creating an ASCIImation version of Star Wars. The Frequently Asked Questions page for Star Wars ASCIImation is hilarious while documenting the enormous effort required to recreate an iconic movie with only 128 characters and a text editor.

Despite being only 40 percent complete, Star Wars ASCIImation is an absurdly impressive feat

For reasons that are a mystery even to himself, Simon Jansen began creating individual frames of A New Hope after a chain of joke emails. Though not particularly keen on animation or ASCII art, Jansen was just enough of a Star Wars obsessive to keep up with the project.

Obsessive is pretty much the only way to describe Jansen’s project. With more than 16,000 frames at 15 frames per second, the animation only lasts about 18 minutes. It’s not a perfect, shot-for-shot recreation. Those 18-plus minutes manage to cover almost 40 percent of the original. And Jansen had much less than that completed two years after he started the project, when he went viral before it was even a term.

“I do little bursts,” Jansen told Wired in 1999, describing his work ethic toward the project. “...if you were to sit down and a film over days and days, you’d go be a bit strange.”

Wired goes on to mention that LucasFilm was decidedly not a fan of Jansen’s work and the company refused to comment on the article at the time. (Parody versions of Star Wars are nothing new and some even gain praise from Lucas, who reportedly was a big fan of the Family Guy take on the franchise.) This might have had more to do with a seismic shift in Star Wars fandom that happened just as Jansen was getting started.

Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace was released in 1999 to massive hype and drew attention to all things Star Wars, Jansen included. At this point, Jansen wasn’t just known for his burgeoning A New Hope, but also for his ASCII-animated Death of Jar Jar. It has since been removed from the official Star Wars ASCIImation site but you can see it here:

It’s pretty tame, considering what most fans would do to Jar Jar given a chance.

Jansen’s moment in the spotlight was the 1999 Wired piece with him being called, “the creator of what could be considered the definitive ASCII animation masterwork”.

To date, the Star Wars ASCIImation only goes to the scene where Luke finds Leia in holding on the Death Star. It seems that Jansen has finally abandoned the project. The last frame was added in January 2015.

The best part of Star Wars ASCIImation is the loving rendition of the opening scene. It lacks the majesty and spectacle of the original, but you get the point. Jansen’s project started off as a joke, morphed into something bigger, and ultimately was something doomed to be unfinished. Simon is like many rambunctious geniuses, prone to start projects and see them through as long as he’s interested. He’s built better nerf guns, restored cars, among many other random and wonderful projects. Talent often has a way of biting off more than it can chew.

In a rare moment when an expert offered advice that turned out to be true, Richard Ashcroft, a game designer and animator that worked with Universal Pictures, said, “He’s done a fantastic job but he could have edited the thing down to three minutes. It’d be much more accessible and he’d get his life back.”

If you bother to watch all of Star Wars ASCIImation, you’ll notice Jansen taking more “artistic license” with dialogue towards the end. Painstaking recreations give way to characters literally saying, “Bah” and destroying things in frustration. (Something that didn’t happen in that particular scene.) Even stretched over 18 years, with a schedule designed to prevent insanity, the work finally drove Jansen to quit.

Some labors are just too much.

:format(jpeg)/2018/06/tedium062118.gif)

/2018/06/tedium062118.gif)

/uploads/andrew_egan.jpg)