Ink-Stained Pixels

The Kindle and the Nook have defined the eBook, but there are literally decades of prior art for this device—an idea many readers still haven’t warmed to.

Today's GIF comes from a Sony Data Discman commercial that was attached to the U.K. VHS release of the film "Bob Roberts."

“The man who inserts an electronic book into his computer, then sits there and watches it unroll, is a man not to be trusted at a distance. He peruses with glassy stare: so much iron-hard information to be ingested quickly and assimilated thoroughly, then sent away deftly to electronic limbo. The gift of curiosity may be his, not so the gift of enjoyment.”

— William Murchison, a conservative commentator who is still actively writing columns today, describing the possibility of the electronic book in disgusted terms that, unusually, sound a heck of a lot like the way we surf the web in the modern day. Murchison’s commentary, spurred by the presence of computers at the American Booksellers Association’s 1983 annual convention and the larger existential questions they raised for bookstores, really highlights the hill that the manufacturers of eBook technology had to climb in the 1980s and 1990s.

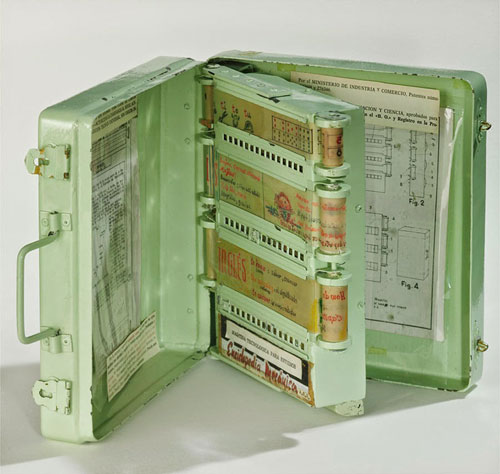

Ángela Ruiz Robles, shown with the Enciclopedia Mecánica. (ITU Pictures/Flickr)

The Spanish teacher who landed upon the eBook’s most important ideas in the 1940s

One thing that’s particularly fascinating to consider is that the electronic book may actually predate any sort of consumer computing device whatsoever—and that it might have come from the world of education, not technology.

Certainly, the machine Spanish teacher Ángela Ruiz Robles came up with in 1949 doesn’t look like what we would consider an electronic book today—it was a machine, really, with visible spindles and information that scrolled horizontally. It included a place for a light source, along with zooming capabilities. (Here’s the patent, in Spanish, if you’re curious.)

But it served many of the same goals that the Kindle and other eBook devices do now. It was designed for children who would otherwise have to carry around massive books to keep learning at home. Instead, the Enciclopedia Mecánica (Mechanical Encyclopedia) allowed large books to be replaced with small, efficient coils—not too dissimilar from rolls of film in size, but with illustrations and writings printed on them. Students scrolled through the book by pressing one of the buttons on the device. Certainly, it didn’t look like a book, but this design was intended to please publishers, as it meant they would be able to print their books on giant scrolls, cutting down the cost of printing a book significantly.

It was a brilliant idea, but one that unfortunately did not find the financial support in its day to gain broad distribution—in fact, just a single prototype was created. And it eventually faded from view.

“There were other priorities in the country and they went for other projects. Furthermore, the implementation of all the specifications of the invention was impractical,” University of Granada researcher María José Rodríguez Fortiz said of the invention, according to the New York Daily News. “In her later years Ángela tried to resurrect the project, when everything was technologically viable. But she did not manage to secure public or private funding."

But in an era when women inventors have been pulled out of the darkness and into the spotlight, Robles’ story has, thankfully, found new currency. In 2016, she was the subject of a Google Doodle in Spain and Mexico, and earlier this year, a street in Madrid was named after her.

Her situation introduces many what-ifs to the story of the electronic book, a tale that generally has leaned heavily on well-known innovators like Douglas Englebart and Alan Kay—definitely prominent figures who had a direct influence on all sorts of devices that we use now, but, in this specific case, not necessarily first.

Robles came to her solution not from a position of world shaking futurism, but practicality, and her device reflects real-world use cases.

Sure, it didn’t use eInk or flash memory, but at a time when our computers used drum memory, it was a stunning idea.

$100M

The amount of money, in computing time, that Michael Hart, the creator of the Project Gutenberg initiative, received in 1971 while a student at the University of Illinois—basically receiving that generous amount of computing access because he knew a guy. He decided to use that basically unlimited amount of computing time to create a project to store large amounts of literature in digital forms—effectively leading to the creation of the largest store of digital information for public consumption in the years before cloud computing, and decades before most libraries themselves went digital. Hart and other volunteers were literally typing in entire books by hand, in an impressive show of crowdsourcing. The project, still active today, is one of the most prominent examples of the public domain in action, the concept outliving Hart himself, who died in 2011.

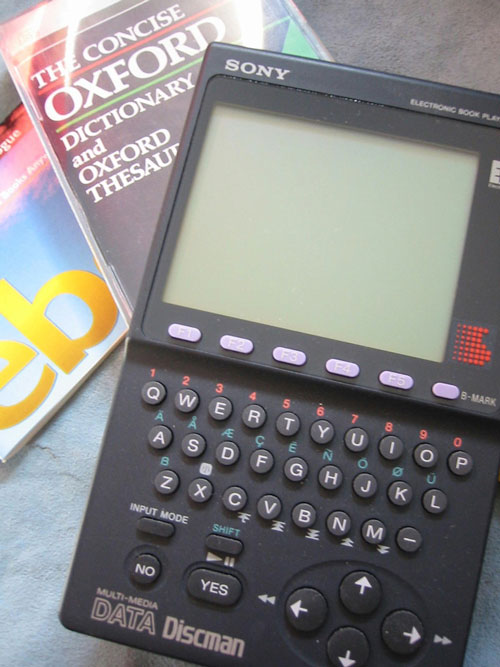

The Sony Data Discman. (_sarchi/Flickr)

Five examples of electronic book readers that predated the Kindle

There was once a time when the vanguard of electronic books was closer in design to a graphing calculator than a book.

The Data Discman, Sony’s CD-based early entry into the realm of electronic books, didn’t look like a Walkman, despite the name, and it wasn’t exactly a world-changer, in no small part due to its limitations.

Chunky in size, the system had a small, monochrome LCD display that was hard to read; the machine used nonstandard CDs that looked like the better-known MiniDiscs but were simply miniature CDs; and it used a proprietary authoring system, ensuring the size of the library would be limited. Oh yeah—when it was released, it cost more than $400.

Despite all that, it was a modest hit in Japan, selling between 70,000 and 100,000 units in its first year, according to The New York Times. A later device called the Sony Bookman accepted full-sized discs and was compatible with DOS, but cost even more. The result? Failure.

Other notable eBook readers that came out before the release of the Kindle:

NuvoMedia Rocket eBook: Inventors Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning saw this LCD-based device, which sold for $499 upon its 1998 release and later for $199, as a key example of how battery life was improving over time. The device gained a reputation as being very holdable, but the screen was an issue, however. “The eBook is pleasant to read for a half-hour at most,” a PC Magazine review explained, adding, “your eyes will start complaining if you use it for longer periods.” Notably, Eberhard and Tarpenning later founded another company that created a device that further highlighted this improvement in battery life: Tesla Motors.

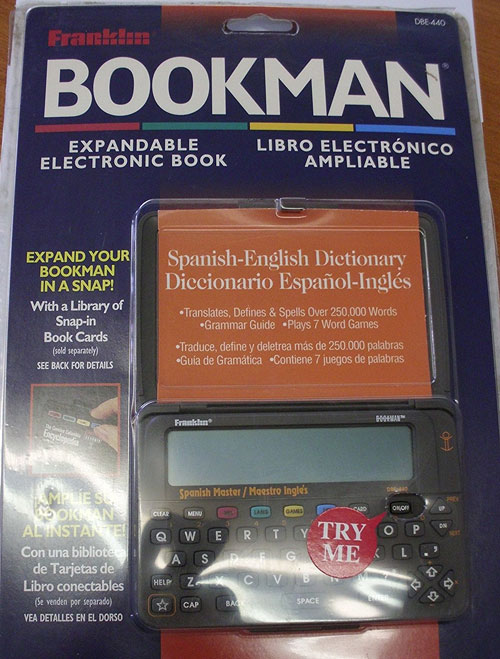

Franklin Bookman: As I wrote about a while back, Franklin Electronics had carved out an important niche for itself as a maker of electronic devices that were cheap and easy to use. In the mid-‘90s, the company started marketing these devices as “electronic books,” though they clearly weren’t intended for novels. The Franklin Bookman, released in 1995 and sold for $130, wasn’t going to compete with the latest Tom Clancy novel, but its cartridge-based system for reference books was an important evolution in the eBook model, and one that was closer to what people needed than the Data Discman.

SoftBook Reader: Released around the same time as the Rocket eBook, the device was something of a mix between an iPad and a Palm Pilot, and had quite a bit of heft—it weighed nearly three pounds, more than twice the weight of its primary competition at the time. Despite paling in comparison to the competition, it deserves notice here for two reasons: One, it was financially backed by Random House and Simon & Schuster; and two, it was a HTML-based device, meaning its internals were fairly unique for the time. Its fate was tied to the Rocket eBook in another important way: In 2000, Gemstar, the maker of the VCR Plus+ and the then-owner of TV Guide, acquired both of their parent companies at the same time.

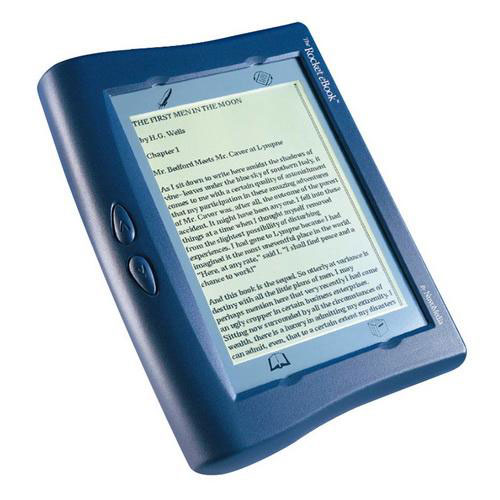

Sony Librie: Despite its failure with the Data Discman, Sony deserves special mention here, in that it released the first eInk-based electronic book in Japan back in 2004. This device, with a 600x800-resolution display, was able to get a lot of mileage out of four AAA batteries—10,000 pages, to be exact—and its design was actually fairly close to that of the original Kindle. But as with many things that Sony created during this era, its proprietary technology—specifically, the use of the Memory Stick and its internal DRM technology—did not help encourage broad uptake. Despite literally creating the first device in a notable market, Sony stopped selling eBooks five years ago.

“Maybe if you had something of this dimension and this weight and as easy to hold as this book. The screen would have to be easy to read, it wouldn't be able to suffer from heat and glare, and you could easily go back and forth from page to page. But I don't see that technology arriving any time soon.”

— Olafur Olafsson, a best-selling Icelandic author, explaining to The New York Times, in a 1994 article, what an electronic book would need for him to want to read it—he compared the desired size to that of his book Absolution. Olafsson, it should be noted, was the president and CEO of Sony Interactive Entertainment at the time and as a result had a direct influence over what Sony did on the eBook front. (Oh well, at least the current Time Warner executive had the PlayStation.)

![]()

Gyricon, the first electronic paper. It used grains of white and black microbeads. (Xerox PARC/Wayback Machine)

The evolution and modern limitations of electronic paper

The secret sauce of the modern eBook is digital ink, the display technology meant to make reading crisp and easy on the eyes. And like the eBook itself, it took a few tries to get electronic paper right.

The concept of came to life in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the same technology lab that brought us the graphical user interface and the laser printer—but the use case wouldn’t be clear to the tinkerers at Xerox PARC for decades.

The needs of one of Xerox’s most fundamental ideas, the Alto computer, inspired the creation of Gyricon, the first electronic paper technology. This material, which was developed after it was decided that the Alto’s monitor wasn’t bright enough, relied on the use of a set of tiny rotating beads that flipped sides with electric charges. The concept was the more promising of two display technologies worked on at the time, but it sat on the shelf for decades without a clear use, and with a corporate parent that showed little interest in anything but printers and copiers.

In an interview with The Future of Things, the technology’s inventor, Nick Sheridon, explained that he only figured out that there might be a market for a paper-like display technology in 1989, nearly 20 years after Gyricon technology was first created.

“I realized that most of the paper consumption was caused by a difference in comfort level between reading documents on paper and reading them on the CRT screen,” he told the outlet. “Any document over a half page in length was likely to be printed, subsequently read, and discarded within a day.”

He was correct that there was room for a paper-like display, but while Gyricon got a lot of attention from Xerox in the ‘90s and early 2000s, it was a competing idea that eventually became the norm for many eBook readers.

The idea for eInk didn’t come from Xerox; it came from MIT—specifically, students who had initially (and unknowingly) considered a solution very similar to Gyricon. But J.D. Albert, one of the founders of eInk, ended up improving on the idea in part because he struggled to replicate the Gyricon approach. According to a 2000 Wall Street Journal article, he wanted to make particles that were half-white, half-black, but instead made some all-white ones. His classmate, Barrett Comiskey, later took those all-white balls, mixed in some dark dye and liquid, and used the phenomenon of electrophoresis—effectively, using electric charges to affect the motion of particles within a fluid—to affect the display of particles on a screen.

An Amazon Kindle. (Duncan Toms/Flickr)

The resulting “page” was high-contrast, easily readable, and didn’t require constant electricity like a computer screen did. Soon, it would be the foundation for eInk, the company. The technology took a while to gestate, but soon became good enough for e-readers like the Kindle.

Of course, color was a lot harder to pull off using the technology they had created than it’s been with comparable LCD technology, and as a result, it took years for eInk to develop a color screen that showed up in an eReader. In fact, the company’s first try at it totally flopped. So did the competition’s. Color may be a “killer app” for digital ink someday, but it needs to be good enough to properly reproduce those colors first.

However, we’re getting closer to a good-looking variation on color eInk. Three-color eInk panels are relatively easy to find, and the company has a technology called Advanced Color ePaper in the works, which it’s pushing for digital signage rather than eBooks at the moment. A competitor, CLEARink, is aiming more directly at bibliophiles.

Other display technologies have surfaced over the years to give digital ink some competition—including “electrowetting,” another display technology Xerox PARC originally worked on in the 1970s, but none have managed to topple the approach taken by eInk—yet.

The electronic book had a lot it was going against before the release of the Kindle. It still does, really.

In ways unlike any other format, the physical book—spine and all—has seen defenders repeatedly come out of the woodwork over the years, and numerous studies put out since the release of the Kindle have given fodder to eBook skeptics who aren’t ready to give up trees just yet. Even in cases where the economic advantages seem obvious, like with college textbooks, the digital forms haven’t won out entirely yet.

Perhaps this skepticism has been a driving factor in the bounce-back of real books over digital ones—eBook sales reportedly fell nearly 20 percent in 2016 and another 10 percent in 2017. But on the other hand, it’s simply hard to ignore the fact that there wasn’t really much of a market at all before eInk-based readers finally came into their own, and importantly, Amazon (with the Kindle) and Barnes & Noble (with the Nook) created marketplaces that made digital content plentiful and easy to acquire.

When it comes down to it, it was that mixture of technology and content that proved so vital. Perhaps a Kindle or Kobo never will feel exactly like a book, but it got close enough for a large number of readers that the difference stopped mattering.

Perhaps we’ll never be rid of the world’s oldest content format. Maybe the Kindle is as close as we’ll get to digital books replacing physical copies. But it’s been an interesting read watching the tech world try.

:format(jpeg)/2018/04/tedium042618.gif)

/2018/04/tedium042618.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)