It’s Not HBO, It’s UHF

The quickly forgotten phenomenon of scrambled television stations that ran over the air on UHF signals. Not everyone had cable TV at first.

P.S.: Can anyone figure out what’s going on here?

Sponsored By … Nobody?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

Wait, why would people want to buy TV on UHF? Didn’t they have cable?

As it turns out, cable television just wasn’t moving fast enough for the tastes of the big-city American public, and the early structure of the cable television industry was a big reason why.

The industry wasn’t controlled by a handful of companies like Charter and Comcast; it was the realm of a country full of startups, all of which had to lay wire in homes around the country. Home Box Office, or HBO, was awesome, but it just wasn’t an option in most homes for more than a decade after its 1972 creation.

A good comparison point here is the drawn-out process to get fiber-optic cable installed in cities and neighborhoods around the country. We’ve made progress on this front, but we’re still decades off from full coverage. (Hong Kong had better luck.) Verizon FiOS is great if your neighborhood has it, but the company is weirdly slow about expanding its reach; Google has essentially given up on its fiber dreams.

Cable was a highly factionalized industry, and people willing to take crazy risks, like Ted Turner, were richly rewarded in the long run. But, in the short term, most of the public was left out, even in major cities like New York, Los Angeles, and Washington.

And that created an opportunity for UHF (ultra high frequency), a type of television signal that was, for a number of years, ignored by the TV-watching public, despite the fact that it greatly expanded the number of options available via broadcast. In 1962, the federal government passed a law called the All-Channel Receiver Act that required new televisions to support UHF (ultra high frequency) signals, but even after that, UHF was treated as a second-class citizen on the television dial and it took some homes many years to upgrade to a set that could support the wider channel ranges.

Nonetheless, while it wasn’t perfect, UHF helped make room for public television stations, for locally-owned channels without any ties to a national network, for religious broadcasting, and for home-shopping services.

And for a time, UHF also made room for premium television.

1931

The first year that Zenith had experimented with pay television systems, later launching its Phonevision system in 1951. (That 1931 date is only around five years after John Logie Baird invented the television, by the way.) The Phonevision service, one of many small experiments of the early television era, attempted to scramble signals that would could be descrambled through ownership of a box. In its most notable run, it was active in the Hartford, Connecticut market from 1962 to 1969.

Isaac Blonder and Ben Tongue (via Blonder's website)

The inventors who set the stage for the pay-television movement of the 1970s

Perhaps the most pivotal figures in television history that you’ve never heard of are a duo of inventors named Isaac Blonder and Ben Tongue.

Between the two of them, they are responsible for dozens of basic broadcasting patents that helped to reshape the television dial in some important ways—including by stretching the reach of UHF signals. Founding a company called Blonder-Tongue Laboratories in 1950, the duo is responsible for creating many of the technologies that we take for granted today when watching the boob tube. Despite both having passed years ago, the company that bears their name still lives on today.

The inventors could even be described as a bit offbeat. In 1971, Blonder was taking his electronics equipment to Scotland in an effort to see if he could find the Loch Ness monster.

He never did find Nessie, but when he got back to the office, he helped discover something else just as elusive: A way to make UHF competitive with cable television, a goal that had fallen through Zenith’s fingers a few years earlier.

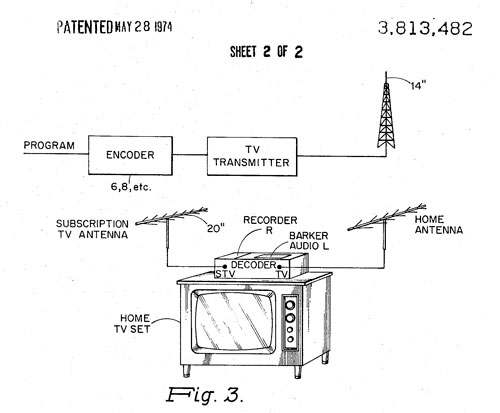

A drawing from Blonder's descrambler patent. (Google Patents)

In the 1950s, Blonder-Tongue had attempted to sell the Federal Communications Commission on a pay-TV service of its own called Bi-Tran, which would allow for two types of signals to run through the same channel—one free, and one pay, with the pay version made available through the use of a telephone line. Later, the duo came upon their own way of scrambling television signals, earning a patent for such a process in 1965. Another patent, filed in 1972 by Blonder and granted in 1974, described the use of a decoding device, or a descrambler, that homes could use to access premium television signals.

It was an impressive feat of engineering, and Blonder-Tongue’s work would soon find a place in cable systems around the country. But first, Blonder-Tongue would put its descrambling devices through their paces on UHF—on the Newark, New Jersey station WBTB-TV, channel 68.

From this perch, Blonder-Tongue launched a local television network that The New York Times would describe as “part‐free, part‐pay,” with decoders needed to watch shows during some parts of the day, and free television available at other times. Viewers were only charged while the decoder was on.

“Ultimately, the choice of programs will be entirely in the hands of the viewers,” Blonder said told the newspaper. “They will not pay for what they don't want to see, and they will not have thrust into their homes presentations they do not want to have.

The network soon flopped, however, going off the air just a few months after it was launched, with the subscription model soon dropped and not much to show for it other than the homegrown success of The Uncle Floyd Show, one of New Jersey’s iconic counterculture phenomena.

The problem wasn’t the idea, but the execution—Blonder-Tongue just wasn’t built to run a TV station. But just a couple years later, Channel 68 would become home to a pay-TV station that might not have been fully owned by Blonder-Tongue, but certainly relied on its descrambling technology.

And that channel, known as Wometco Home Theatre, wasn’t alone, either.

28

The number of hours that subscription television services were required to air unscrambled programming before 1982. The rule was rolled back by the Federal Communications Commission after the commission decided that the rules were limiting the growth of the model. “[Subscription television] should be given the opportunity to develop on an equal footing with conventional television since it can respond directly to the intensity of consumer preferences, and therefore serve the public interest,” the FCC said, according to Congressional documents.

Meet the premium channels that time forgot

Wometco, a company with a name only Tronc could love, was once an empire of a company. The Florida firm once owned one of the state’s largest movie theater chains and purchased a number of television stations around the country. It also owned the Miami Seaquarium, one of the first oceanariums in the country.

And in 1977, the company took the concept of Blonder-Tongue’s UHF pay-TV station and turned it into Wometco Home Theatre, the connective tissue that brought premium television to four of the five boroughs of New York City. (Can you believe Manhattan had cable decades before everyone else?)

If you lived in NYC and wanted to watch commercial free movies, sporting events, or … uh … after-hours stuff of the kind you might find on Cinemax today, it was the way to go. By 1979, it had nearly 40,000 subscribers, who were willing to pay $15 per month, plus installation and deposit fees, for access to a single over-the-air channel that aired premium movies at a time when cable television was rare and home video was even rarer.

And it wasn’t alone, either. A few other networks that operated using a similar model in the 1970s and 1980s:

ONTV: Perhaps the scrambled UHF network with the largest reach, ONTV operated in Chicago, Minneapolis, Detroit, Los Angeles, and numerous other cities. Its greatest claim to fame, however, might be the fact that in 1982, George Lucas agreed to let the channel air Star Wars in a special pay-per-view format—making it the first time the film aired on TV. At a time when VCRs were fairly uncommon and Hollywood movies on home video formats even less so, this was a Big Deal.

PRISM: This Philadelphia-based network, thanks in no small part to its close ties to Philly sports—it was run as a joint venture by the man who owned the Philadelphia Flyers and the company that owned the Spectrum sports arena—survived well into the 1990s, though it only spent a few years as a UHF-based service. (Side note: There was also a UHF-based service out of Chicago called Spectrum; no relation.)

SelecTV: One of the longer-running UHF-based satellite channels, SelecTV merged with ONTV in the mid-80s and stuck around in one form or another until around 1991. Three particular notable things about the service: The service produced a sketch comedy show called “Channel K”; it was at one point available unscrambled for satellite owners, though the gravy train eventually ran out; and in Los Angeles, the network would air films up for Oscar consideration so voters would be able to watch them from the comfort of home.

Z Channel: A special case needs to be made for Los Angeles’ Z Channel, which didn’t actually air over UHF but was very much in the spirit of the other channels. The network, which was affiliated with local cable provider Theta Cable, reached areas without cable access using a microwave technology called Multipoint Distribution Service. The channel, which was well regarded among film buffs for its eclectic film selections, is best known today for airing the near director’s cut of Heaven’s Gate, the Michael Cimino film that became an icon of overambition.

SuperTV: This local premium channel, based in Washington, DC, and nearby Baltimore, took advantage of the fact that the region had cable penetration of only around 10 percent in 1981. The upstart leveraged a geographical quirk; DC and Baltimore’s close proximity allowed it to offer many of its customers two kinds of programming for one price. It had some competition, however, in the form of Marquee Television Network, a microwave-based service that distributed HBO in the area, and SuperTV struggled to keep momentum in the market, never switching to a 24-hour schedule and shutting down entirely in 1986. (Side note: It was rumored at one point that the Russian embassy was messing with Marquee’s signal.)

1990

The year that Sky television launched in New Zealand. The service, which is better known as a satellite service today, initially launched using analog UHF signals instead of satellites, a signal that reached three-quarters of the country by 1997. (The service did require outdoor antennas, however.) The service offered major networks, such as CNN, Nickelodeon, and the Discovery Channel, all through scrambled UHF signals. The country didn’t get a satellite-based Sky offering until 1997, and the UHF signal was still active all the way until 2010.

The thing that’s really striking about the U.S.-based services, nearly all of which folded by the late ‘80s or early ‘90s, is that they were clearly waystations for cable or satellite television, offerings that were clearly better in every way and offered up far more options than any of these services could muster through traditional broadcast.

And the impression they left, in many ways, was minimal. (With the exception of Z Channel, of course, which benefited from its eclectic nature and proximity to Hollywood.)

If you didn’t grow up in a major metro area in the early ‘80s, odds are you probably didn’t even know about them at all, because FCC regulations were initially written in a way that discouraged pay TV stations to show up in markets that only had three stations otherwise.

The channels, based on their advertising, read sort of like alternate universe takes on pay cable channels. They were designed to show movies and sports, and they often heavily promoted the featured product, just like a free weekend of HBO.

But for cord cutters in the 1980s, these channels had nowhere to go. HBO and Showtime eventually made their names on original programming that was as high of caliber as the films each network aired.

The best SuperTV or ONTV could hope for? Fuzzy memories on the UHF dial—memories that would become even fuzzier after Fox became a thing.

:format(jpeg)/2018/04/tedium042418.gif)

/2018/04/tedium042418.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)