Consumer Conflict

From literary advocacy to union battles to communism claims, the origin story of the organization that publishes Consumer Reports kind of has it all.

Editor’s note: We have a few new faces tonight on the email list—in large part because our prior piece, on 3Dfx, drew the highest single day of traffic in our history. Whoot! Anyway, hey guys! Make yourselves at home.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

A copy of Your Money’s Worth, a pivotal book in the consumer movement. (via Rare and Out-of-Print Trading and Financial Books)

The standards nerds who formed the basis of the consumer rights’ movement

The thing about watching a video from a guy like iTwe4kz is that you’re watching, really, for his opinion, which is likely to be loud, brash, opinionated, and not entirely impartial. That’s not a knock on him. That’s just the way YouTube works—we watch videos for the opinions shared.

But the problem, of course, is that biases swing in all directions, and in a world where you’re getting marketing at every single second. A lot of people read this in their inboxes. And a lot of the messages surrounding it are often promotional or marketing in nature.

And the problem, over the years, has gotten worse. How do you rein it all in?

It was just this sort of problem that inspired authors Stuart Chase and Frederick J. Schlink, who wrote a book titled Your Money’s Worth: A Study in the Waste of the Consumer’s Dollar, in 1927.

The authors were well-positioned to write such a book. Schlink spent years working in various standards bodies, including the United States Bureau of Standards and the American Standards Association (now the American National Standards Institute).

Chase, meanwhile, was an economist with ties to both the Federal Trade Commission and a union-services group called the Labor Bureau. He was also a figure in the Technical Alliance, a group of engineers that pushed for rational solutions to removing waste from the capitalist system. (The latter organization, a figurehead for a technocracy movement, gained currency during the Great Depression, but ultimately faded from view.)

These two men, basically standards nerds who in a way saw commerce as almost a form of engineering, saw the issues raised by the large amount of marketing that consumers were getting constantly bombarded with and aimed for a way to solve the problem: By objectively testing products based on incredibly rigorous standards.

From a passage in the first chapter of the book, which can be read in full on the Library of Congress website:

For the expenditure of about a million dollars, it would be possible to take every current type of motor car made, over a standardized 10,000-mile road test under controlled conditions. (One million dollars is roughly the equivalent of Mr. Ford’s output every two hours.) At the close of the experiment, the figures for each make could be published in parallel columns, without comment. Just the cold figures—so many miles per gallon of gas and oil, so many failures of one kind or another per 1,000 miles, so much braking ability from a given speed, so much accelerating capacity, so much tire wear, and so on. Would this help you in choosing your next car? Not if you were buying primarily to make an impression on the neighbors. But if you really wanted to get back of the advertising, the high-powered salesman, and the dandy little jiggers on the dashboard, and find out what was the best car for your needs and for your money—it would help tremendously. As the motor car becomes increasingly a utility and decreasingly an emblem of swank, the help to the main body of purchasers would be untold. In the end such a list would set up standards of performing excellence, and force persistently inferior types off the market altogether. For the million-dollar outlay—in a three billion dollar a year industry—who shall say what savings in hundreds of millions would be repaid to the American people?

Your Money’s Worth spoke about the dangers of quackery, the importance of standards, and the ways that people trying to make a quick buck misrepresent themselves. The duo goes through a laundry list of people trying to screw the 1920s public out of their money.

“We believe that the foregoing evidence indicates only too clearly that there are significant groups of products, in which the production of sound goods, accurately described, and sold at a fair price, has not been the dominating motive of those in control of the process,” the authors write in a chapter on companies that misrepresent themselves. “We have seen that in the case of refrigerators, soap and cleansing agents, textiles, furs, weighing scales, paints, heating and cooking devices, varnishes, even loaves of bread, there exists an enormous burden of adulteration, bad workmanship, misrepresentation, sharp practice, and even downright bodily danger, which falls back upon the consumer. And who shall say how much is preventable if the consumer could be armed with the findings of impartial analysis and test?”

(Perhaps those who spent their hard-earned money on Kanoa headphones should read this book.)

The book was a mainstream success, of course, and was a selection in the Book of the Month Club, ensuring it had a mainstream audience.

This mainstream attention created an opportunity for the two men to help tackle the issues with testing and validation that were sorely lacking from the consumer space. In a 1928 interview with the New York Times, Chase noted that the book helped encourage the National Retail Dry Goods Association to create its own testing apparatus, at a cost of a 30th of a percent of the industry’s total gross output.

“Signs are multiplying that this country is definitely headed for an era of consumer buying governed by set standards or specifications,” Chase told the Times. “The manifold response to our book clearly indicates this.”

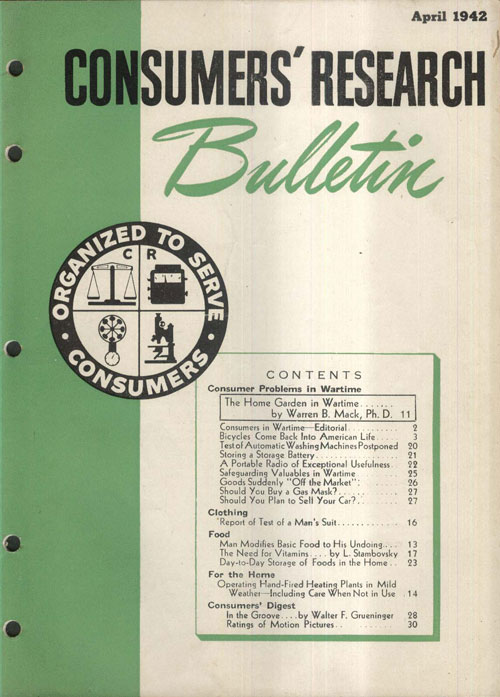

Consumers’ Research Bulletin, the publication of Consumers’ Research.

It did draw a ton of attention, and the book inspired local clubs around the country—consumers were inspired to act and share information about the products they buy. Chase and Schlink set up an organization called the Consumers Club. And in 1929, that organization became Consumers’ Research, a nonprofit organization that is still active today.

Schlink, who lived to the age of 103, actively led the organization for more than 40 years, complete with testing facilities, and it still exists today. (He is called the group’s driving force on its website.)

However, you may be forgiven for not knowing about it, because it was overshadowed by another organization that does the same thing: Consumers Union.

And there’s an important reason for that.

“Some forty or fifty thousand persons won’t so much as buy a box of dog biscuits unless F.J. gives his ‘O.K.’ … obviously they think most advertisers are dishonest, double-dealing shysters.”

— C.B. Larrabee, the publisher of the magazine Printers’ Ink, offering up a take (relayed via the 1999 book No Logo) on Consumers’ Research, which was known for rigorously testing product claims, which it published in its magazine, called Consumers’ Research Bulletin. According to Inger Stole’s 2010 book Advertising on Trial, Consumers’ Research published two separate versions of the magazine—one for general circulation, another for subscribers. The subscriber version, which often veered into more libelous territory, was sent out to readers who promised to sign pledges not to share the information in the magazine beyond their immediate household.

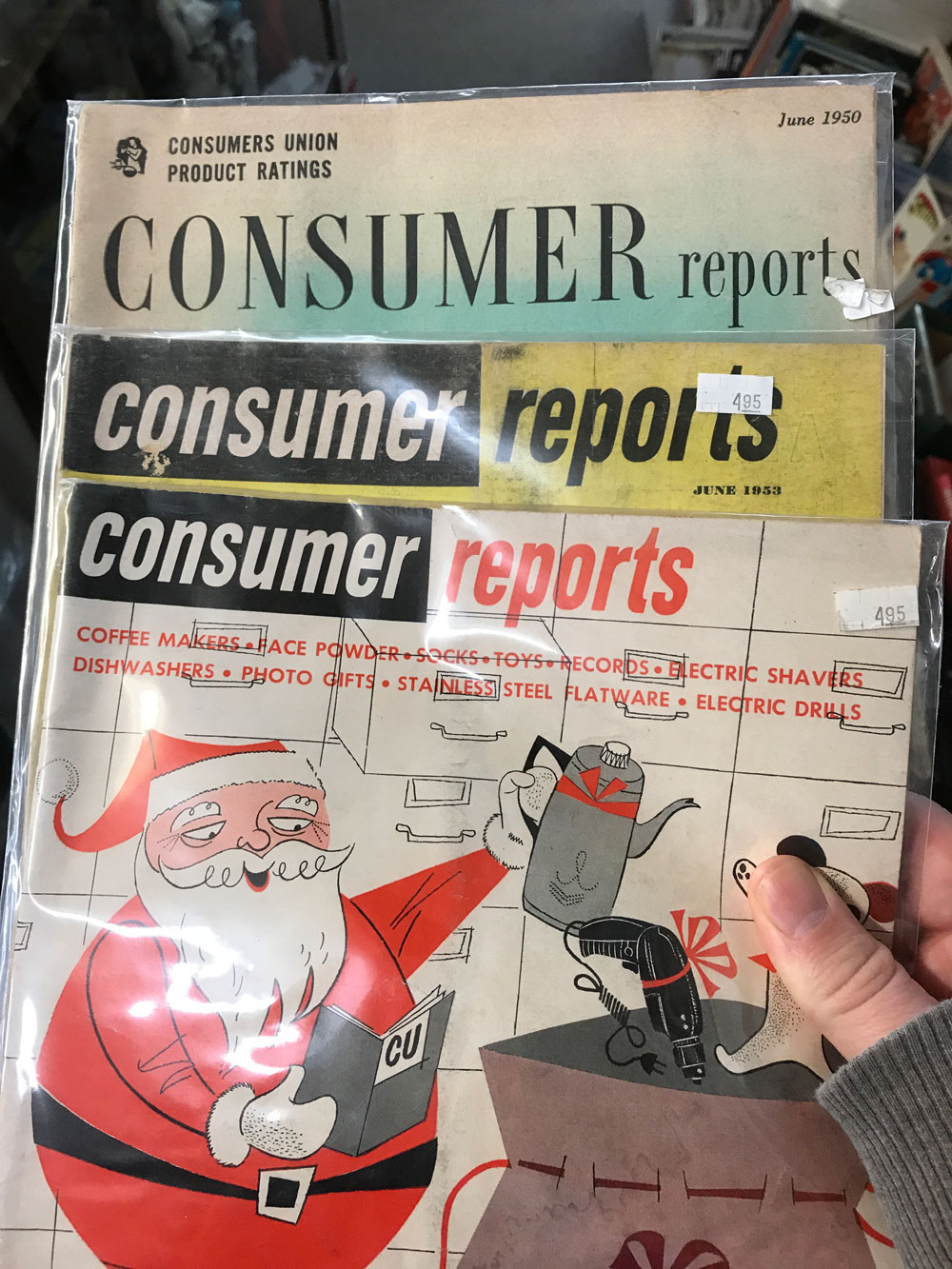

A few vintage Consumer Reports issues I picked up recently. The top one is nearly 70 years old. (photo by me)

The union battle that reshaped the way that consumer groups operate

It’s wild to think about the fact that Consumer Reports, the major magazine that offers fair, research-focused reviews of all sorts of consumer products, has consistently published for more than 80 years.

I was stunned recently when I was digging around an old comic book shop and purchased fairly pristine copies of the magazine, dating from the early 1950s, for about $5 a piece. The magazines look nothing like the glossy version that you’ll find today, but the lineage is clear.

That lineage, however, is more complicated than you might think it is. See, the reason why Consumer Reports exists is very messy, and points to a chasm in the consumer advocacy movement that cuts to the heart of what that movement is about.

The magazine, oddly enough, has its roots in a labor strike. In September 1935, concerned by what they considered unfair labor practices, 41 workers walked off the job at Consumers’ Research, which by this time had become part of the vanguard of the consumer-rights movement and was considered a bastion of liberalism at the time. But all was not well inside its doors.

Part of the problem, per Lawrence B. Glickman’s 2009 book Buying Power, A History of Consumer Activism in America, was that the organization actually followed a technocratic approach, one that focused on serving the consumer’s needs, but not really pushing past that point.

“While they claimed to champion the ‘consumer interest,’ technocratic individualists understood such an interest in rigidly circumscribed terms, as dues-paying members relying on experts like themselves to critique business practices and to highlight cost-effective, quality goods,” Glickman wrote in his book.

This created a division internally—between those who saw the role of a consumer organization as one focused on offering a service to the public, and one focused on advocating for the consumer’s rights, politically. Mix in a labor conflict like the six-month strike that went down at Consumers’ Research—which was based around issues such as over wages, turnover, the rural location of the organization’s facilities, and Schlink’s top-down leadership style—and suddenly you have enough tinder for a full-on schism.

The strike, which was at times violent, created an opportunity to assess the ideological differences in the consumer movement. While the strikers were ultimately vindicated by the National Labor Relations Board in 1936, Consumers’ Research ultimately chose to ignore the ruling, and by the time the strike ended, many striking workers were inspired to launch a separate organization, Consumers Union, the publisher of Consumer Reports. (Today, Consumers Union is now known as Consumer Reports after a 2012 name change.)

Consumers’ Research had issues with the products being sold to consumers, but ultimately supported the capitalist ends behind those products, and chose not to take a more activist approach, which represented the root of the union complaints. But Consumers Union, the offshoot group created by onetime CR board member Arthur Kallet and Amherst College economics professor Colston Warne, had no problems with going full activist and using their vantage point as a perch for launching a larger political movement.

“The economic system will be in perpetual ill balance under the present system,” Warne said in a 1937 speech critical of the Roosevelt administration, according to the New York Times. “Future crises are inevitable unless some drastic economic reorganization is effected.”

The problem, as it turned out, was that Schlink and others affiliated with Consumers’ Research believed that the founders of Consumers Union had gone full communist. And that belief deeply infected the strike itself and the early years of Consumers Union’s existence.

This belief was particularly carried through by J.B. Matthews, a Consumers’ Research executive who Glickman characterized as taking a “journey from the far left to the extreme right,” a move that in the long run saw him becoming the head of research for the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

In an interview with the defunct publication Stay Free, Advertising on Trial author Inger Stole noted that the grudge created by the union battle ultimately had an effect on how far Consumers’ Union would go with its activism, as the communism attacks especially stung. Consumers’ Research, which lost its place in the conversation to Consumers Union, did not help to dissuade the communist attacks, and Stole implies that Schlink’s jealousy over the issue may have been a root cause.

The result was that Consumer Reports, which started as a much more politically minded endeavor, was softened into something much more mainstream and practical in the end.

“I think they got tired of being attacked. It happens to even the most courageous. To focus on product testing and Consumer Reports was politically safe and made economic sense,” Stole said in the interview.

“All the technical information in the world will not give enough food or enough clothes to the textile worker’s family living on $11 a week.”

— A passage from the first editorial that ran in Consumer Reports, an essay intended to differentiate Consumers Union’s work from that of Consumers’ Research. In the end, while Consumers Union does much in the way of activism—most recently speaking up against the Equifax breach and the recent changes at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau—its approach isn’t quite as hard-edged as it was out of the gate. That’s not to knock it, just to state fact. It certainly could be worse: In recent years, Consumers’ Research has gained a reputation for “astroturfing,” particularly on behalf of the tobacco industry; the Center for Media and Democracy’s SourceWatch notes that the group “has ties to the tobacco industry and has published a number of misleading reports by industry-funded apologists.” (That’s pretty far from where it started.)

The modern version of Consumer Reports, which needs no introduction, is a treasure of a modern, mainstream publication. It’s one of the most important magazines on the shelves, and one that goes to great extremes to test things. While Consumers’ Research may have had the idea of running the giant testing lab, it was ultimately Consumer Reports that followed through.

A magazine after my own heart.

Among the things it tests include mattresses, including those of the hipster variety, so of course I’m smitten.

And the company is not afraid to go toe-to-toe with some of the world’s largest and most prominent companies. In 2010 it ingratiated itself with the tech world by taking on the iPhone 4 in the middle of Antennagate, leading to a rare situation where Steve Jobs had to throw out a public mea culpa.

And the company isn’t afraid to take on buzzy names like Tesla if they think it’s necessary.

But the wild thing is this. This magazine, and the organization that runs it, has this wild origin story that most people are totally unaware of. Considering the attacks and the battles that Consumer Reports went through in its earliest years, it must be no skin off their nose to have to deal with an angry tweet from Elon Musk. They’ve already falsely been called communists, so how much worse can things get?

Maybe iTwe4kz should work for them as a product reviewer.

:format(jpeg)/2018/02/tedium021518.gif)

/2018/02/tedium021518.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)