When Copyright Goes Copywrong

The rigid nature of copyright law during the early years of the film industry created a surprisingly robust cottage industry around public domain films.

Today's GIF features Al Lewis, a.k.a. Grandpa Munster, as he's shown in his 1980s-era public domain VHS film series.

Sponsored By … Nobody?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

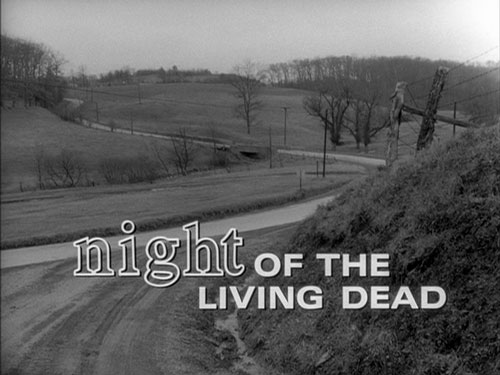

“Nobody noticed the copyright notice had come off. Three or four years into the film’s release, a lot of people noticed that the film had no copyright on it. And it remains, to this day, in public domain. It’s a technicality we argued for fifteen years.”

— George A. Romero, discussing the fate of his most famous film’s copyright in the book Night of the Living Dead: Behind the Scenes of the Most Terrifying Zombie Movie Ever. The copyright issue, created by the original wording of this section of the Copyright Act of 1909, is seen as a mixed blessing for the film. While it cost Romero and other creators a lot of money and led to attempts to remake or revamp the film to help protect its copyright in some way, it likely helped popularize the film’s vision of zombies within popular culture.

The lack of copyright notice on this screen put Night of the Living Dead in the public domain—not an uncommon mistake, as it turns out.

The copyright hiccups that befell George A. Romero and lots of other filmmakers

The Copyright Act of 1909 came before much of the film industry we have today, and it shows.

The law—which very specifically calls for works to include a variation of the word “copyright,” a date, and rights-holder for a work—is the root for a lot of the problems that the film industry faced with copyright during this early era.

These problems were largely solved with the Copyright Act of 1976, which added a section specifically to handle cases where situations of copyright notice omissions occurred.

“Unintentional omission of the notice and comparatively trivial errors in its form and position have caused forfeiture in a number of cases,” the U.S. Copyright Office noted in a guide to the 1976 law.

It didn’t help works created before 1978 of course, which meant Romero and his ilk were out of luck.

Another issue that has come to light over the years is the failure to renew copyright, which specifically affected works created between 1923 and 1963—a particularly fruitful era for the film industry. Prior to 1923, all works are in the public domain, meaning films like D.W. Griffith’s infamous 1915 epic The Birth of a Nation, for example, are fully in the pubic domain.

Thanks to the Copyright Renewal Act of 1992, all works created during or after 1964 are automatically renewed—that year being relevant because works created in 1964 were still in the original 28-year period of copyright at that time. But for works created prior to 1964, copyrights needed to be renewed manually—and quite often, they weren’t.

There are many examples of films that failed to do this, most notably 1946’s It’s a Wonderful Life, which fell out of copyright in 1974, slowly gaining its mainstream status thanks to incessant replays on television during the ’80s and ‘90s.

The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, the 1998 law named for the then-recently-deceased pop-star-turned-Congressman, expanded the life of copyrighted works even further, to 70 years after the death of their creator, or for as long as 120 years after creation in the case of corporate ownership. But works that didn’t get renewed before that point didn’t fall under that law.

However, legal cases have created some wiggle room for some works, most notably It’s a Wonderful Life, which benefited from a 1990 Supreme Court ruling that found that copyright holders had certain rights over elements of a film, like the story, even if the film itself wasn’t copyrighted. That helped Republic re-secure the rights to the film from copyright purgatory.

Good for the legacy of Jimmy Stewart, whose film Rear Window was the subject of Stewart v. Abend, the pivotal ruling for It’s a Wonderful Life. (George Romero was out of luck, however, because he never had an original claim to the film he created.)

Most recently, the U.S. Supreme Court, in 2012’s Golan vs. Holder, found that Congress can pass laws to renew copyright for works that had fallen into the public domain—something it did in 1994, in an effort to protect foreign works under the Berne Convention, a 1988 copyright treaty. So Congress, theoretically, could pull things out of the public domain if it so chose, though Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, in her opinion, suggested that a more aggressive approach taken by Congress wouldn’t pass the court’s muster.

To be fair, copyright law was broken in some obvious ways and needed to be fixed—and creators got punished as a result. But films unintentionally in the public domain created some nice side effects within popular culture.

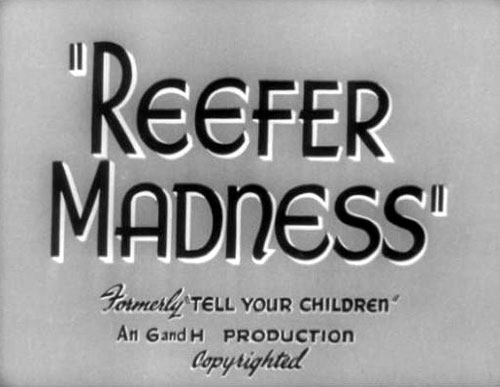

Simply saying your film was "Copyrighted" wasn't enough for the Copyright Act of 1909.

Five notable examples of films that accidentally fell into the U.S. public domain for various reasons

- Reefer Madness: The infamous 1930s anti-pot propaganda film just says “Copyrighted” on the title, which doesn’t really fit the rules of the Copyright Act of 1909.

- Charade: The Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn film, a big-budget Universal Pictures release, fell out of copyright immediately upon release because the title screen failed to actually use the word “copyright,” instead stating “MCMLXIII BY UNIVERSAL PICTURES COMPANY, INC. and STANLEY DONEN FILMS, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.”

- Santa Claus Conquers the Martians: This infamously not-very-good 1964 film, which I watch every single holiday season, does not include any copyright information with either the title or the ending—something I made a point of double-checking for you guys.

- The Terror: This 1963 Roger Corman film, which didn’t have any copyright info attached, relied on a series of uncredited directors, giving it a bit of a hodgepodge feel—something most assuredly not helped by the fact that Corman attempted to add new scenes to the film in the early ‘90s in an attempt to gain some semblance of copyright control.

- Three Stooges shorts: Most of the short slapstick films produced with Larry, Moe, and a rotating cast of third bananas fall under copyright, but four such films—Malice in the Palace, Disorder in the Court, Brideless Groom, and Sing a Song of Six Pants—were never renewed, meaning they’re more common than most of the other sketches.

1164

The purported copyright year of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, the popular 1964 Christmas special. (Specifically, it lists its date in Roman numerals as MCLXIV, rather than MCMLXIV.) Due to copyright law, there’s some belief that the film might be in the public domain due to the date error and the film falling under the Copyright Act of 1909, though other elements of the story, much as with It’s a Wonderful Life, have copyrightable elements.

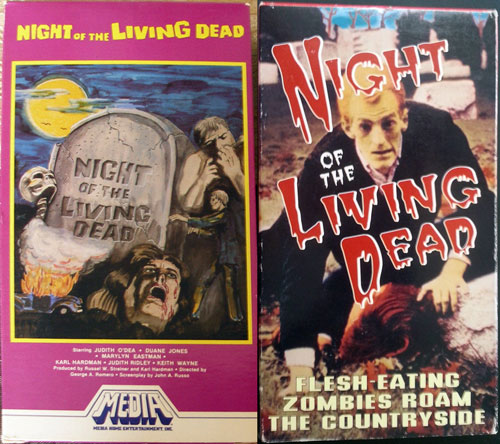

Two of the many Night of the Living Dead public-domain VHS releases. (via The VCR From Heck)

How manufacturers took advantage of copyright laws to help build out the video industry

In the early 1980s, major studios seemed to not be interested in playing ball with the home video market in any realistic way.

Some of the earliest attempts to price disc-based films hovered around $1 to $10, but those price levels quickly got thrown out the window.

When it came to VHS, out of concern for their bottom line, the studios tried selling new-release movies for $60 or more a pop, which both dampened demand for new releases and drove the creation of a video rental industry. Eventually, the film industry realized that it needed to make changes, first cutting the price of some high-profile films to $39.95, then famously putting a Diet Pepsi commercial on the VHS release of Top Gun, helping to bring the price of the tape down to a relatively reasonable $26.95.

But the confusion on how to price new releases created an opportunity for companies to come in and release older films on the cheap. And some of the oldest, cheapest films were, of course, the ones in the public domain.

In 1982, the Indiana video production firm Kartes Video Communications, along with a few other companies, hit on what turned out to be an important trend: The low cost public-domain movie. The company, which was founded in 1974, wasn’t the first to hit on the concept of releasing classic films on the budding VHS format (The Nostalgia Merchant, an early video distributor that released a mixture of public domain and acquired films, was among the first), but Kartes was perhaps the one that found the winning strategy: Price the films high, but not too high, and focus on creating a quality product.

“A lot of these films are in public domain,” founder Jim Kartes told The Indianapolis News in 1985. “Anybody can get an old print and start dubbing off copies. The trick is to get access to a good negative library and make clean sharp copies. I have the exclusive rights for seven years to one of the best libraries.”

Kartes was far from alone with his dubbing machines, which were pushing out as many as 250,000 copies per month at the time of the article—including films like It’s a Wonderful Life.

And other experimenters were out there as well. Hal Roach Studios, a firm whose namesake founder was responsible for some major early-Hollywood franchises (most notably Laurel and Hardy), also got into the public domain game around this time—though Roach’s twist was that he was pushing to colorize old black and white films—including It’s a Wonderful Life, which the firm was ironically able to copyright in color form.

Some video producers aimed high; others aimed low. But they were often working from the same collections of old movies, cartoons, and shorts.

Night of the Living Dead was well-represented among public domain replicators, of course. As the public-domain-film-themed Tumblr site The VCR from Heck pointed out a few years ago, Romero’s iconic film has been released by public domain VHS and DVD distributors numerous times over the past 40 years, with numerous takes on box art, cheap intros, and even multiple attempts at colorization.

There are so many versions of Night of the Living Dead, of varying quality and approach, that you could literally become a collector of just this one film and never hit the bottom.

Speaking of things hitting bottom, it was very much a race to the bottom for public domain films on VHS—which often varied wildly in quality and quickly gained a low-rent reputation.

Public domain films as a result, are often copies of copies of copies—fuzzy and faded, whether you’re watching old Three Stooges episodes, Plan 9 from Outer Space, or The Little Shop of Horrors. Don’t expect HD quality, let alone 4k.

These days, sites like the Internet Archive and even YouTube have taken the place of these bulk film dubbers.

But it’s worth arguing that these public domain video sellers helped create a market that more thoughtful copyright owners have come to take advantage of.

The badly dubbed films helped make room for the big-budget releases.

1987

The year that former Al Lewis, a.k.a. Grandpa Munster, first opened up his restaurant Grampa’s Bella Gente in Greenwich Village. (The odd spelling of “grampa” was intentional, by the way, so as to avoid trademark issues.) In her 2015 book I Married a Munster!: My Life With “Grandpa” Al Lewis, A Memoir, his wife Karen notes that Lewis leveraged the attention that his culinary adventure afforded him to move into a number of other fields—including a show on TBS and a series of VHS videos built around public domain films, all based on the “Grampa” theme. Here’s a sample of Lewis’ public-domain work.

Public domain films, whether or not they’re any good, can create a culture of sorts around their existence—something clearly on display with both the VHS releases of the ‘80s and Mystery Science Theater 3000, a show that has created a whole secondary world around terrible, often public domain, films.

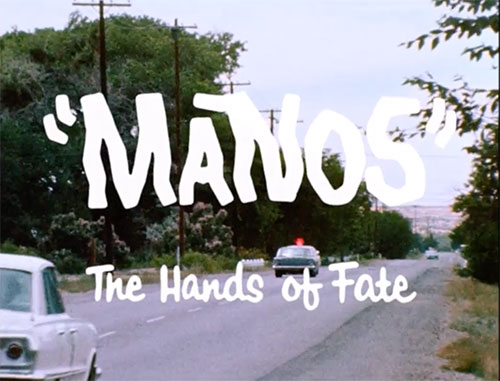

See anything missing here?

One of the most famous MST3K public domain revivals, a movie called Manos: the Hands of Fate, has thrived culturally as a result of this status. Even if the film itself is an unintentionally hilarious mess, it’s worth more now than it was 51 years ago, released just two years before Night of the Living Dead.

But there has been a debate in recent years around the film’s copyright status. Joe Warren, the son of the film’s director Hal Warren, is currently trying to make the case that the film was never in the public domain, despite the film not having the necessary copyright notices—much like Romero’s film.

His evidence? A copyright for the screenplay—which on its own may not be enough to protect the film.

As Playboy reported in 2015, the film’s ownership has become complicated, particularly after movie fan Ben Solovey went to the trouble of launching a crowdfunding campaign to do a full restoration on a print of the film he discovered. (The restoration came out on Blu-ray in 2015, and is eligible for copyright.)

Currently, Warren is fighting to trademark the name of a movie that was released 51 years ago, while Solovey is raising a legal defense fund to fight against this belated rights grab on GoFundMe.

Why fight? Per an update on the crowdfunding site: “Free access to creative works in the public domain can enrich us all in ways that we might not expect,” Solovey writes.

Maybe its copyright status was a happy accident, one created by a law that never anticipated accidents.

But all this copyright confusion did create something important of value—made all the more obvious in the digital era.

We should do everything we can to protect it.

:format(jpeg)/2017/10/tedium102417.gif)

/2017/10/tedium102417.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)