Scanning And Sorting

How the banking industry, with an assist from tech, turned an incredibly frustrating, manual process—sorting checks—into an excellent example of automation.

Editor’s note: Thanks to Kristen Gallerneaux, a curator of communication & information technology at The Henry Ford, for the idea for this one.

The Prepared is a newsletter for non-engineers who love engineering

In this week’s issue: Infographics, literally on parade, during 1913's Municipal Parade of New York City Employees. Subscribe for free here!

Today’s Tedium is sponsored by The Prepared.

“During my reign as a rip-off champion, not one out of a hundred tellers or private cashiers paid any attention to such numerals, and I’m convinced that only a handful of the people handling checks knew what the series of numbers signified.”

— Frank W. Abagnale, the subject of the biographical 2002 Steven Spielberg film Catch Me if You Can, describing in the book of the same name how humans failed to decipher the number-based system used by the checking system, especially after things went electronic in the 1960s. Abagnale was aware of the numbers and famously took advantage of them to defraud banks of millions of dollars—then, after he went to jail, he helped the banking industry improve its security.

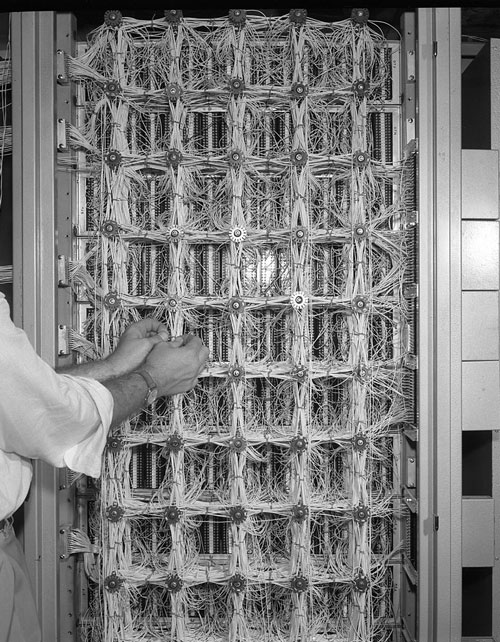

Ken Eldredge, who worked on the ERMA check-scanning project. He was given a patent for the invention of MICR, a key technology used for scanning checks even today. (via Internet Archive)

How physical check scanning pushed the computer industry forward

Back in 2017, I pointed out, sort of in passing, that an early innovator in optical character recognition was the banking industry.

That’s absolutely true—if you pick up a check today, it features the same variant of chunky font that was developed in the 1950s.

But what I didn’t really discuss in depth with that article was how the banking industry got into the check-scanning game. It’s worth diving into in no small part because it was one of the first major uses for computers by the business world and one that genuinely proved, in a useful way, that computers could beat humans at menial tasks.

Here was the problem: In the years after World War II, checks became hugely popular as a form of exchanging currency. The problem was, the banks themselves could not keep up with the sheer demand, and, as a 1993 article from IEEE Annals of the History of Computing explains, the job of processing checks was pretty terrible at the time:

In a 40-person branch, at least seven people were employed as full-time clerical workers. Most were young female bookkeepers between the ages of 18 and 24. Their monotonous work mainly consisted of sorting pieces of paper, running an adding machine, and bundling checks. Not surprisingly, considering the drudgery of the position and the age of the women, who traditionally left the banks upon marrying, the turnover rate was exceedingly high—in some areas reaching 100 percent turnover each year.

The challenge was such that some banks had to close their doors by 2 p.m. to even manage the high numbers of checks coming in.

This necessitated a new approach, and that approach took the form of Electronic Recording Machine, Accounting (ERMA), a project of the Stanford Research Institute (SRI), an official arm of the university meant to help jumpstart the local economy. (Not sure if you’re aware of Silicon Valley, but it worked.)

A computing project launched at the behest of Bank of America, the incredibly complex device was designed to not only read checks (not running into any issues with checks below $100 million in value), but to organize them in a way that was manageable for banks.

The project, which required a whole lot of coordination, along with the invention of multiple new technologies, came about starting in 1950, as Bank of America struggled with the sudden glut of checks, asking SRI to assess the issue.

The computerization of the banking industry came down to a chance meeting between SRI executive Dr. W.B. “Hoot” Gibson, who had a promotional event near Bank of America’s headquarters, and the banking giant’s senior vice president, S. Clark Beise.

“I told Beise that this was just a ‘shot in the dark,’ but that I thought Bank of America should be thinking about electronic applications,” Gibson said, according to the IEEE article. “He expressed some

concern about whether the bank would ever get what was really needed from IBM, Burroughs, and other such companies.”

And with that conversation, it was soon off to the races. SRI researchers, led by computer scientist Jerre Noe and engineer Tom Morrin, worked on the project for a number of years afterwards, having a version for testing available by 1956 and the device showing up in Bank of America locations by 1959. This was not a small project, and the team met with numerous other companies to build the peripherals this machine would ultimately need.

Not many wires at all. (Wikimedia Commons)

Being the first try—and coming before, y’know, microprocessors—the machine was insanely complex, and a 1955 SRI newsletter did not shy away from this fact.

“ERMA includes more than one million feet of wiring, 34,000 diodes, 8,000 vacuum tubes, and it weighs in the neighborhood of 25 tons. It uses 80 kilowatts of electricity broken down into six voltages and generates enough heat to warm three eight-room houses. An air-conditioning system cools it,” the article noted.

From a practical standpoint, the SRI project helped pave the way for two main applications used in modern-day banking: Magnetic ink, which was paired with the fledgling OCR technology of the era to create magnetic-ink character recognition (MICR), and check-sorting machines, which took the most manual part of the process, paired it with character recognition, and made it possible to sort checks by machines.

This primitive amalgamation of machine with task became a key turning point for the banking industry, as it helped to set the stage for point-of-sale systems, for modern-day credit cards, and for all the crazy crap that’s coming down the pipeline next.

“In spite of our famous mass-production system, with its incredible speed and fertility, our use of human resources is still shockingly bad. Millions of people are doing only a fraction of what they are capable of doing. Modern mass-production techniques may be highly paid in dollars, but they are guilty of demands upon the human spirit as arrogant as the worst sweatshop of old.”

— A quote from Let Erma Do It: The Full Story of Automation, a 1956 book by David O. Woodbury. (He’s better known for, among other works, Atoms for Peace, a book that shares its name with a Thom Yorke supergroup.) The book expanded on the basic ideas of the ERMA project and suggested that numerous forms of automation would eventually overtake all parts of the work day—a prediction that turned out to be so right that the New York Times review of the book was titled “An Amazon Helps Out.” (Since I first wrote this, a friend of mine got a copy of this book in the Internet Archive.)

An IBM 3890 document processing machine, a common type of large check scanner. (Wikimedia Commons)

How we moved from a handful of huge check scanners to a bunch of small ones

While the Stanford Research Institute, now known as SRI International after splitting off from its namesake university in 1970, set the stage for the electronics to shape the checking industry, other companies would come to define the sector.

While SRI built the prototype, General Electric ultimately built the production machines, which replaced SRI’s tubes with transistors. The company’s heart was never in it, though, so the firm eventually sold off its computing interests.

MICR became an industry standard, however, after the American Bankers Association adopted the technology for the industry at large, making room for competitors like IBM to get into the space.

One of the most prominent and interesting of these competitors is Burroughs, which was a major computing firm during the 1960s and 1970s. The company, with roots as the Burroughs Adding Machine Company (and whose founder, I kid you not, was the grandfather of William S. Burroughs), eventually became one of the best known proponents of check-processing technology.

Case in point: The company eventually became Unisys after a merger, but when Unisys spun off its check-processing operations in 2009, the firm was called Burroughs Payment Systems.

Burroughs’ check-reading technology was particularly fast—a 1959 Detroit News article noted that its machine could handle 1,560 checks per minute, 50 percent faster than any competing machine on the market. It was a speed so fast that it directly inspired the design of the punch-card reader on one of its computers, the B5000.

And that was only the starting point—by the mid-1970s, further innovations, such as IBM’s Check Processing Control System, helped the banking industry process many, many more checks.

A 1977 Cincinnati Enquirer article on that city’s regional Federal Reserve Bank really highlights how advanced the check-scanning field really became. Using a Burroughs B4700 computer, the Federal Reserve was plowing through as many as 90 checks per second on five different sorting machines. The five machines could plow through 65,000 checks an hour, or half a million a night.

People were still involved in the process—37, to be exact—but clearly there’s no way this process could have been done overnight just two decades prior. This would have been the job of thousands of people.

A Burroughs SmartSource check-scanning machine, along the lines of what a teller or small business might use today. (via The Henry Ford)

These days, check processing, thanks in no small part to improved optical scanning technology and digital innovations along the lines of electronic funds transfer (EFT) and automated clearing house (ACH), has become much less centralized. If you walk into a bank, the teller is likely to scan the check using a machine behind the counter, rather than handing it off to be processed elsewhere.

A good way to think about this: What’s easier, scanning thousands of checks at once, or processing the check in an electronic form at the moment it’s pushed into an ATM?

Laws have further eased things as well, with 2004’s Check Clearing for the 21st Century Act making it possible for the creation of something called Remote Deposit Capture (RDC), which allows companies to process checks in their own offices using small machines, rather than giant ones. (If you’ve ever scanned a check using your phone, same idea.)

Businesses, rather than handing their checks to the bank, might instead use a small machine that scans the full check into a digital file, rather than handing it to the bank. Before its check-scanning arm was acquired in 2016 by Digital Check, that was the business Burroughs was in.

It took us 60 years, but we completely flipped the model from a handful of huge machines to millions of small ones.

It’s worth noting that all these changes to checking came with their good and bad.

A good example of this: You know how you can buy a gift card for, like, Starbucks or Whole Foods, and it’ll have a really cool design on it? Sometimes, they’ll even be die-cut.

It turns out that they used to do this with checks, and they had to stop doing that as a direct result of the changes to the checks, so that they would go through these machines. The checks could no longer be oversized, they had to have a certain shape, and they needed to have the magnetic ink code somewhere. It was a buzzkill for graphic designers, of course.

“Like buyers of Model T Fords, banks can have magnetic ink characters printed in any color they choose—as long as it is black,” New York Times reporter Albert L. Kraus explained in a 1960 article.

But what might have been a frustration for creative people ultimately was a shot in the arm for the banking industry. It solved a practical problem—so many checks that no amount of humans could read them—with an automated solution.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal!

And thanks again to The Prepared for sponsoring us these past few Wednesdays.

:format(jpeg)/2017/09/tedium083117.gif)

/2017/09/tedium083117.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)