Sing Your Heart Out

From 8-Track to Laserdisc to CD+G to ISDN lines to YouTube, the different technologies that made karaoke possible. (Alcohol helps, too.)

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

“Inoue's own story is as inspiring to every anonymous worker as those of Eiji Toyoda or Akio Morita: after all, the man who helped make us all Sinatras cannot read a note of music, plays the keyboards only ineptly, he says, and has made next to nothing from his invention.”

— Pico Iyer, a contributor to Time, discussing the tale of Daisuke Inoue, the man from the suburbs of Osaka, Japan who came up with the idea of karaoke in the early 1970s. Inoue, famously, failed to patent his idea for music-making machines, allowing others to do so later on. Inoue, who explained his early experiences in launching karaoke in Topic magazine in 2005, noted that the hard part about making the concept happen was not so much the technology—certainly, it wasn’t easy, since he was using eight-track tapes in his original machine, the Juke 8—but the record labels, which were not organized in a way to make selling karaoke an easy process.

An eight-track karaoke player from Japan. (via Yahoo! Japan Blogs)

The thing not to be missed about karaoke in Japan: It was a home phenomenon, too

Around the time that small, tinny keyboards were taking the U.S. music market by storm, karaoke machines were basically doing exactly the same thing in Japan.

And while the technology has long been associated with bars and restaurants, it showed a surprising amount of influence on the home market in Japan. Despite being relatively new to the market in the early 1980s, home karaoke machines had impressive saturation: They sold 1.4 million units in 1983, according to the Los Angeles Times, and could be found in 13 percent of Japanese homes. And these machines weren’t cheap, either: A basic set cost $400 or so in the early ‘80s. According to the book Karaoke: The Global Phenomenon, Japanese spent more on karaoke equipment than Americans spent on gas appliances in the early 1980s.

(Hell, even the Famicom had a karaoke game. So too, did the Mega Drive.)

It’s understandable why this was the case. It had a lot of real advantages as both a form of entertainment and a way of making money. Not only did it benefit restaurants and bars, but it also created a cottage industry for vendors who would serve and service the machines, manufacturers who could design innovations around karaoke technology, and the music industry suddenly had a new way to generate a whole bunch of performance royalties.

A vintage home cassette karaoke machine from Japan. (Yahoo! Japan Auctions)

That said, the technology behind karaoke was a little rough at first—first sold in eight-track format, lyrics not included.

In the late 1970s, however, the first attempts at video took hold, and by the early 1980s, the Japanese company Pioneer had built its budding Laserdisc technology around the karaoke concept.

Our perception of music would never be the same.

65

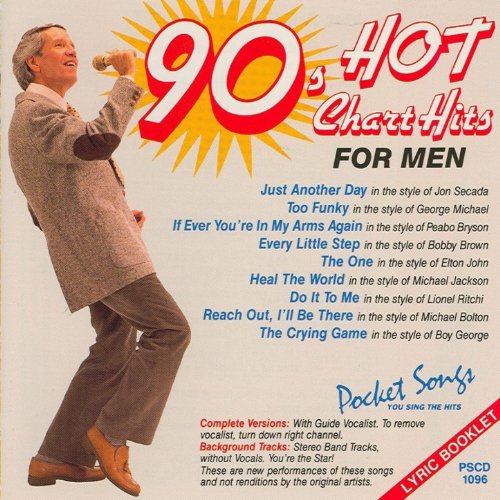

The number of manufacturers of karaoke equipment in the United States by May of 1992, according to Billboard. Among the largest companies were the ones that licensed the songs from the music industry, such as Pocket Songs and Sound Choice. Major technology companies, like Pioneer and JVC, were also big players in the karaoke industry during this era. There was not a karaoke industry in the United States a decade prior, but it was a big enough deal that the Summer Consumer Electronics Show that year had a dedicated event to highlight the karaoke industry. (And it was still growing in Japan, too—“karaoke boxes” alone were a $3.8 billion business in Japan in 1991, per the Billboard article.)

A LaserKaraoke machine. (leighklotz/Flickr)

How karaoke quietly pushed technology forward in the 1980s and 1990s

The karaoke format, of course, was good for bars, restaurants, and record labels in the ‘80s. But the real winners might have been the ones producing optical discs during this time.

With its LaserDisc format and Japanese roots, Pioneer was in a stronger position than most to take advantage of the growing interest in karaoke. The company launched a dedicated Laserdisc karaoke player in Japan in 1982, soon integrating digital sound, allowing it to overtake the country’s market in just a few years. Pioneer was well-suited to overtake this niche market for one specific reason: Its main competitors at the time, VHS and Betamax tapes, were linear in nature, but Laserdisc was chapter-based and random-access in nature, like a DVD. The result was that it could be used more akin to a jukebox in format, with a single disc holding more than two dozen songs.

Eventually, Pioneer brought LaserKaraoke to the U.S. in 1988. While the medium had shown signs of potential success, the company had to convince bars and restaurants to make a fairly expensive investment in technology that they might not necessarily use every night. In some ways, the approach was truly innovative—thanks in no small part to the jukebox-style format of the karaoke discs.

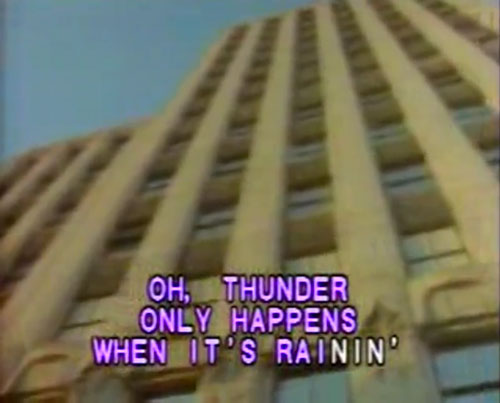

Dreams by Fleetwood Mac, in karaoke form.

Certainly, Laserdiscs had the capacity to be perfect for karaoke, but the challenge was the sheer size of the library the technology had to support. A 1991 review of a LaserKaraoke machine in Popular Electronics should sound familiar to anyone in the U.S. who has performed karaoke in the last 25 years:

Although the video portions of the karaoke discs tend to have some relevance to the lyrics and spirit of the song, they'll seem amateurish to anyone who was raised on MTV—and some are downright funny. For instance, Steppenwolf's "Born to be Wild"—the "theme song" from Easy Rider—replaces the 1960's hippie/druggie bikers Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda with a 1990's yuppie photojournalist who travels with his camcorder from continent to continent on his motorcycle. Oh well, the disc producers know that the video is just background for the real star—the karaoke singer.

The problem, as The Outline pointed out last year, was budgetary—while Pioneer had more money for film production than its many competitors, the budgets (around $6,000 a pop) were minuscule compared to traditional music videos. (The Internet Archive, of course, has a giant collection of ‘em.)

In his book Shooting Movies Without Shooting Yourself in the Foot: Becoming a Cinematographer, author Jack Anderson noted the challenges this created for filmmakers.

“Everything had to be done as simply and cheaply as possible in the least amount of time,” he wrote. “At the same time, the result was expected to be very dynamic, very visual and entertaining. Sure.”

(On the other hand, as Brian Raftery’s Don’t Stop Believin’: How Karaoke Conquered the World and Changed My Life notes, it was a much larger budget than for most karaoke content, which looks like this. Plus, as the discs sold for $150 each, the margins were huge.)

Laserdisc, as a format, had a reputation for being a cinephile’s dream, its add-ons playing no small role in that. But ultimately, most people experienced it in a non-cinephile format—at a karaoke bar, probably with some awkward interpersonal dynamics going on.

In a lot of ways, the format’s weaknesses (particularly its cumbersome size) left open opportunities for competitors to appear over time.

A karaoke disc, for men. In the words of the immortal Jon Secada: I … I don't want to say it.

First up was CD+G, a variation of the traditional CD format that took advantage of unused portions of the traditional CD to offer a visual layer. Some musical acts, like the synth-pop band Information Society, actually used CD+G for their records, and the format was supported by video game consoles like the Sega CD and Philips CD-i but it quickly became the domain of karaoke. The format, which could only display low-resolution graphics was much more limited, of course, than LaserDisc, but it was probably a fair tradeoff.

Eventually, a couple of stronger competitors showed themselves: The Video CD, a less-expensive variation on the LaserDisc, appeared in 1993. And in the Japanese market, the videogame developer Taito (previously best-known for Arkanoid) had created a method for distributing karaoke songs through an ISDN phone line, making it possible to have larger libraries than ever before.

And while DVDs eventually appeared, greatly improving quality, it turned out that the idea of cloud-accessible karaoke proved the real disruptor in the country that first created the concept. Sure, it wasn’t as good at first—it relied on pre-programmed MIDI at a time that LaserDisc could pump out actual music that was produced in a studio—but quality, as it turned out, wasn’t the main factor.

“Online karaoke could be considered a ‘destructive technology’ for existing karaoke,” noted IP Friends Connections, a publication of the Japanese patent office. “Before online karaoke emerged, the main focus of technical innovation in the karaoke equipment industry was improving the quality of music played and creating videos to accompany the songs. MIDI was inferior in quality to the existing karaoke, but far superior in updating the latest tracks and convenience.”

Soon enough, the internet would do this to basically every other industry.

3.1M

The current number of subscribers to Sing King Karaoke, a YouTube channel whose claim to fame is that it produces instrumental karaoke tracks, many of recent hit songs. (As of this writing, 24 of the channel’s songs have more than 10 million views.) The team’s production process, according to TubeFilter, involves a number of studios and multiple tracks being worked on at once. “We are very conscious of our instrumental quality being the best it can possibly be, so we always prioritise sound over speed,” the creators wrote.

Now, the weird thing is that karaoke may not have the level of buzz it did during its 1980s and 1990s peak (Carpool Karaoke aside), it is still generating innovations in the business world.

That’s despite the fact that smartphones can do literally everything a karaoke machine could do in 1992. In fact, smartphones are actually inspiring some of the newest twists.

The latest and most interesting one comes from China. In recent years, the miniKTV, a phone-booth-sized kiosk, has made self-service karaoke possible. While you’re out and about at the mall, having just filled up on Kenny Rogers Roasters, you can walk into one of these booths, belt out a few tunes, and upload the results to WeChat or a similar service—or even record your own album, on the fly. Basically, it’s a karaoke recording booth, and it’s driving a ton of investment interest in China at the moment.

"The development of mini-KTV meets the demands of young people in current society, who live fast and fun lives and are eager to make good use of their spare time," business analyst Liu Dingding told the Global Times last month.

The mall-karaoke trend goes against the public performance concept that generally drives karaoke technology forward, but the folks doing it don’t seem to mind all that much.

“No matter how good or bad I sing, nobody can judge me, and I can just have my moment,” noted Li Rui, a miniKTV fan from Changchun, to Xinhua.

The karaoke bar, by nature, is supposed to be a no-judging zone. But hey, if the privacy of a random mall kiosk will cull the best possible performance out of you, then by all means.

Sing your heart out.

:format(jpeg)/2017/08/tedium081017--2-.gif)

/2017/08/tedium081017--2-.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)