Cheese, American Style

Despite cheese existing long before the U.S. did, it has come to define American food culture globally—and not just because of American cheese. Why is that?

Editor’s note: This piece is an update/reframing of an older piece of mine regarding the word “America” and branding. I felt that the post hadn’t aged particularly well, minus the cheese part, so I wanted to take a second stab at slicing it up. The cheese part of that story was removed and given a sizable expansion here; the branding part of the old story still stands.

Sponsored By 1440

News Without Motives. 1440 is the daily newsletter helping 2M+ Americans stay informed—it’s news without motives, edited to be unbiased as humanly possible. The team at 1440 scours over 100+ sources so you don't have to. Culture, science, sports, politics, business, and everything in between—in a five-minute read each morning, 100% free. Subscribe here.

“There is one good reason why cheese in the American factories will never detract from the popularity of Cheddar, or Cheshire, or Stilton. The Americans can imitate English cheese admirably in appearance, but not in flavor. Our importations from America are consumed chiefly by those who do not consider any particular flavor essential.”

— An 1882 article from the The Pall Mall Gazette, a British newspaper, critiquing the qualities of American cheese compared to its U.K. equivalent. The article did note, however, that American cheesemakers did repeatedly work to improve their product over the years, “with all the customary energy of their race,” and were starting to catch up in at least one sense. The article makes the case that British dairy farmers, who were getting outclassed by their American counterparts in the marketplace on the sales front, should “club together” to take on the growing, factory-driven apparatus of American cheese.

The Canadian guy who invented the gooey stuff we call American Cheese

James L. Kraft may have spent his childhood as an Ontario farm boy on the wrong side of the U.S. border, but like Ted Cruz on a presidential campaign, his legacy is purely American.

By nature of his upbringing, he had already been exposed to the process of making cheese, and as he reached adulthood, he brought this knowledge to the other side of the border, first by spending time working in a nearby Buffalo dairy.

Soon enough, he found himself in Chicago, with a couple of bucks and a deep knowledge of cheese. Starting in 1903, Kraft began to offer a service to local grocery stores. Early in the morning, he went to the city’s main cheese market, tracked down the kinds of cheese grocers were likely to want, and then delivered it to stores in a horse-drawn wagon.

After doing this a while, he noticed something—specifically, how quickly the cheese would spoil in grocery stores. This was a significant problem for a number of reasons, the biggest of which was that this meant cheese didn’t hold up very well in warm climates. On top of this, cheese had other problems as well–many cheeses didn’t melt evenly and would essentially disintegrate when heated. That led Kraft to begin experimenting with cheese, in an effort to create something that lasted longer and was easier to use.

Meanwhile, a couple of guys in Switzerland were focused on the same problem. When experimenting with a local brand of cheese called Emmental, Walter Gerber and Fritz Stettler figured out that by using sodium citrate on the cheese while it was melting, the cheese molecules would stick together and hold up perfectly. (This YouTube clip explains why, if you’re curious.)

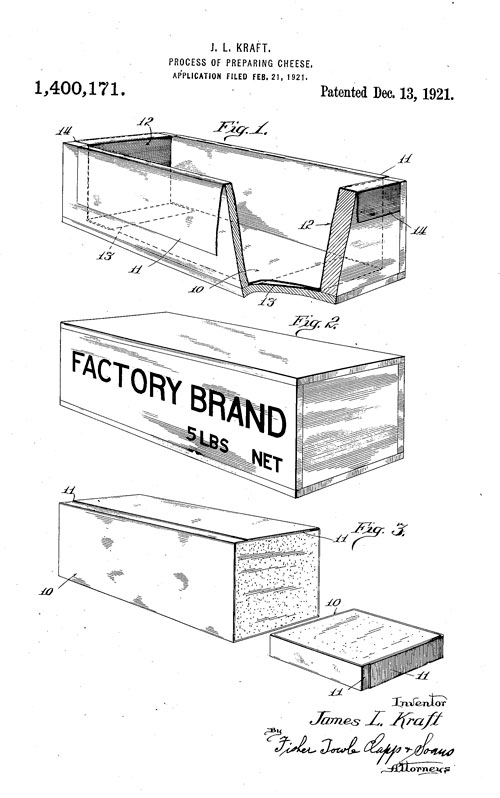

Five years later, Kraft was starting to patent some of his own strategies, which also focused on the idea of melting the cheese, but into a specific shape. His first such patent, filed in 1916, he filed his first such patent, for a variety of cheese that stores without quickly going bad, that melts without losing its general character.

“The chief object of the invention is to convert cheese of the Cheddar genus into such condition that it may be kept indefinitely without spoiling, under conditions which would ordinarily cause it to spoil, and to accomplish this result without substantially impairing the taste of the cheese,” Kraft stated in his initial patent claim.

A later patent filed by Kraft gave the processed product a vessel: a box,lined with metal foil, in which the cheese product was placed into while still in liquid form, and set aside to solidify. (The result had a lot in common with the modern form of an early Kraft company acquisition, Velveeta, though unlike that semi-liquid product, the final product was solid, like traditional cheese.)

The process of making American cheese, which was effectively pasteurization, broke some key rules in terms of what cheese was supposed to be (specifically, loaded with bacteria), but it was hard to argue with the results, or the sales. Culture: The Word on Cheese’s Grant Bradley put it as such:

The cheeses of yore, handcrafted in tiny batches on individual farms and later whipped up en masse in large factories, arrived at the local grocer in huge wheels (the most economical way of transporting them and keeping them fresh). James and the rest of the Kraft brothers, however, began to occupy an entirely new production paradigm. Their cheese wasn’t shaped into wheels and aged in a cave—it was a gloopy mass that was heated up, stirred in a cauldron, and removed of all bacteria. It could take on any shape.

It took a few decades for the resulting American cheese to take on its most famous form, as a sliced-up sandwich utility, wrapped up in individual packets. (Kraft’s brother, Norman, did much of the work on that front.) But we wouldn’t have reached that point without a Canadian dude who was obsessed with cheese.

Considering how much processed food we eat, American cheese may be the most American food of all.

I had to filter out “incident” to find this photo of string cheese on Flickr. (k.steudel/Flickr)

Five types of “American” cheese that aren’t American cheese

- Monterey Jack cheese: This California-based variety, with apparent Spanish and Mexican roots, came about under its current name due to the influence of a major land-owner in the Monterey, California, region in the mid-19th century, David Jack. There is some debate over whether Jacks came up with the cheese himself, or simply formulated the supply chain that led to its success. Whatever the case, he’s the one who earned the naming rights. (Regarding pepper jack, things get hazy, but it likely went to market between the late 1970s and early 1980s.

- Colby cheese: Befitting Wisconsin’s place on the modern cheese culture map, it only makes sense that the state is responsible for the wholesale creation of a popular type of cheese. In 1882, Joseph F. Steinwand came up with Colby in an effort to create a new variant of cheddar cheese. (He succeeded.) The cheese, which had more moisture than traditional cheddar, is named for the town it’s from, Colby, Wisconsin.

- Cream cheese: While there’s some evidence of predecessors in the history of cream cheese, the invention of cream cheese as we know it, according to Billy Penn, involves a New York dairy farmer and a smart marketer. Why “Philadelphia,” then? Easy. It was good for branding.

- String cheese: This processed take on mozzarella cheese was created by another Wisconsinite, Frank Baker, who noticed that by taking mozzarella and dipping it in brine, the cheese took on a string-like functionality. However, it wasn’t clear at first that the cheese would be sold in ultra-portable packages, according to a 2014 Atlantic piece. That came later.

- Baby Swiss cheese: Don’t let the name fool you—the cheese may have been inspired by Switzerland’s Emmental cheese, but it’s a wholly American invention, the product of a Swiss immigrant who built an empire in Ohio with his Guggisberg Cheese brand. Alfred Guggisberg’s invention, named because it looks like a miniature version of swiss cheese, first came about in the 1960s.

An example of a refrigerated warehouse at Springfield Underground. (Handout photo)

The underground lair where Kraft stores its cheeses before selling them

For more than 55 years, Kraft Foods has been doing something kind of weird and kind of interesting—the kind of weird and interesting that causes one to do a double take when they learn about it.

Here’s the deal: For decades, the company has been the largest tenant of an underground mine, which they basically use to store food, especially cheeses, for long periods of time. The company, which has a large cheese processing facility in Springfield, Missouri, has long been willing to spend a whole lot of money to keep its cheese pristine, along with other products that the conglomerate is known for.

Which is where Springfield Underground comes into play. The mining site, which was first cracked open in 1946, soon became known not just for its limestone, but for its immense storage space that was a side effect of a whole lot of underground digging. In 1960, the company mining the land took advantage of the fact that it was mining underground to build out controlled cave environments for different business use cases. Kraft signed on board in 1962, and it got the facility hopping almost immediately. A 1963 Springfield Leader and Press article described the cave as “one of the biggest storage warehouses in the Midwest.” Here’s what Kraft’s part of said facility was like:

Another portion of the cave, containing 110,000 square feet, is under lease to Kraft Foods Co., and is jammed virtually to the doors and rafters with raw cheese collected from plants throughout the middle west. It’s a particularly busy operation, with railroad cars and trucks moving in new supplies each day and with aged cheese being moved to the Kraft plant on South Glenstone for processing.

Since then, Kraft has expanded its use of the facility, and at times uses as much as 750,000 square feet of space—or about 13 football fields worth of storage.

In 2015 comments to the Springfield News-Leader, Kraft spokeswoman Joyce Handel explained that the warehouse—kept at a constantly chill 36 degrees, below the mine’s standard temperature of 62 degrees—is both a shipping hub and a storage site.

“All of our Springfield plant’s refrigerated products go to the Springfield Underground for storage and are picked up for distribution there,” Hodel explained to the newspaper. “Some products from other Kraft plants come to the Underground and are then combined with Kraft Springfield products to form full loads of shipments to go to customers in the middle part of the country.”

Now, Kraft isn’t alone in putting its stuff in the cave—the facility attracts a variety of tenants interested in needs like data centers or long-term storage, along with some tourists—but the multinational food company was the trailblazer of the concept of working in a hollowed-out limestone cave.

But the concept of storing cheese in caves? Not new, of course—lots of cheese-makers do it, even small ones. But Kraft just works at a different scale than everyone else.

Last year, the federal government had to bail out the cheese industry. It wasn’t a large bailout, but one that did cost a little bit of money.

Here’s what happened: Last year, the federal government made two separate $20 million purchases of surplus cheese—one in August, one in October—because the country was at a record level of cheese oversupply. To explain what happened: Cheese production hit a major surge at a time when exports dropped like a rock.

(The government cheese went to charity, by the way, which is great: Cheese and charity don’t always get to work together.)

“While our analysis predicts the market will improve for these hardworking men and women, reducing the surplus can give them extra reassurance while also filling demand at food banks and other organizations that help our nation’s families in need,” then-USDA Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack announced.

But as NPR reported at the time, the USDA’s million-with-an-m purchases of cheese didn’t mean very much when the cheese industry was dealing with a billion-with-a-b cheese surplus; as of last July, 1.3 billion pounds of cheese were just hanging around in caves or storage rooms, just waiting to be used.

It’s a deeply ironic thing in a way: It feels like cheese is everywhere, a gooey reminder of our ever-lingering melting pot. It surrounds our foods, making them just a little bit more flavorful, a little less healthy.

But as it turns out: Often, the cheese stands alone.

:format(jpeg)/2017/07/tedium070417--1-.gif)

/2017/07/tedium070417--1-.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)