The Internet On Dead Trees

Books and periodicals about the internet were a curious phenomenon—in no small part because they frequently pandered to the largest possible audience.

Are you in NYC, San Francisco, Chicago, Los Angeles or Washington DC? We do unconventional tours at the best museums in your city. It’s kind of like the tedium for museums. We don’t talk about the most famous paintings or the newest collection, we find the esoteric stories that make even the “boring art” amazing.

7,500

The number of copies of the book DOS for Dummies that International Data Group printed in its initial 1990 run. Despite low expectations, the book quickly became a massive success, setting the stage for a cottage industry of books that break down technical topics in simple terms, mostly in the computer space. By 1993, the series had sold 1.3 million copies on its own. Now there are 1,950 individual books in the series, covering a whole lot of things that have nothing to do with computing, and the books have sold upwards of 300 million titles. In the ’90s, the series inspired a whole lot of mass-market writing about technology, especially about the internet.

As I recently learned, you can actually buy Free $tuff From the Internet on Amazon. (yeah, that’s my thumb)

What I learned from buying a 23-year-old book on free online resources

Recently, I bought a book—quaint, I know—and I’m probably the only person to have purchased this book or anything like it in more than 20 years.

It’s a reference book, the kind that you can still pick up at Barnes and Noble today. But it’s best described as what you’d get if you combined a phone book, a Matthew Lesko free money guide, and the internet.

The book, titled Free $tuff From the Internet (Coriolis Group Books, 1994), promises to help you find free content online. And, crucially, it focuses less on the web, which is still quite young, than on many of the alternative protocols of the era. The book is a bit tongue-in-cheek, to be fair, but some of the language and descriptions, surrounded by clip-art or screenshots of internet resources, are a little much.

“A revolution in communication is raging around the world, and it’s called the Internet,” author Patrick Vincent explains in the book’s preface. “And whether you realize it or not, you are now on your way to being the latest foot soldier in this latter-day Information Crusade. Welcome to the Internet.”

Conceptually, this book from the get-go speaks to the excitement that the internet generates as an online resource. But, curiously, it was less focused on its value as a real-time tool, and more focused on the idea that it existed as a means to an end. It’s the only thing separating you from more free stuff!

The book—which, much like a Matthew Lesko tome, leans heavily on publicly funded resources like universities or NASA—has a warning in it that it because of its printed nature, odds are very strong that individual links were in danger of going out of date. And, as it turns out … this is not a misleading statement.

Case in point: This book links to FTP sites, telnet servers, and Gopher destinations, and I’ve tried many of them in an effort to figure out whether something, anything in this book works in the present day.

These FTP servers were often based at universities which have a vested interest in keeping information online for a long-term period—think the University of North Carolina, or Kansas State University. But despite this, I could not get most of these servers to load—they were long murdered by the World Wide Web. About half an hour of attempts to load any content whatsoever from these servers led to a whole lot of crying and wasted commands on my terminal screen.

Eventually, though, I hit (a little) paydirt. The first positive match I got for a working server, on page 137 out of a 460-page book, was for gatekeeper.dec.com, an FTP server created by Digital Equipment Corporation and now owned by Hewlett-Packard. But sadly, the resource that I was told I would find there, a recipe for escargot and chanterelle pizza, was no longer there—in fact, the whole recipe folder had been removed. I was only able to find said recipe by typing in a phrase in the book and searching for it in Google. My second positive server match led me to ftp.luth.se, where I was promised a download of Doom. (No dice, but fortunately, it’s not a hard program to find.)

Eventually, the book took me to page 147, where I found a link to a FTP server at MIT (rtfm.mit.edu, to be exact) that had a text file from a Usenet server—a list of MUD servers, to be exact—to find something in this 22-year-old book that was still on the internet in its original form.

That is not a great track record, and honestly, it makes me worry about the state of the internet years or decades from now. Will the links still work?

That’s the big lesson I take from this book: It’s the digital equivalent of walking into a city with a map printed in 1940 and trying to see if things still line up. And honestly, very little—if anything—does.

It’s like we built a new city on top of an old one.

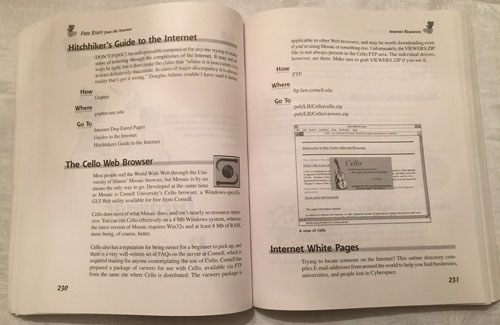

This book gives a shout-out to the Cello web browser, which is pretty cool.

Five interesting facts about the internet you probably weren’t aware of that this book on free internet stuff helpfully points out

- It was possible to get on a text-based version of the internet for free in many areas, using only a modem and a phone line. An entire section of Free $tuff From the Internet offers up a lengthy list of free-nets, grassroots phone systems that essentially allowed for free access to text-based online resources. These networks, often tied to universities or municipalities, couldn’t compete with the internet of today, but are a great reminder that this place wasn’t always so corporate.

- The graphical internet wasn’t necessarily natural at first. Near the tail end of Free $tuff, Vincent spends a lot of time discussing the implications of the then-new NCSA Mosaic (which, unlike nearly everything else in this book, still has links that work!) The chapter, titled “The Tightwad’s Guide to Mosaic,” gets surprisingly technical, given the largely non-technical nature of the book, with much attention focused on the need of acquiring a SLIP or PPP account, setting up a TCP/IP stack, and editing INI files to make sure that everything in Mosaic works. These days, this stuff just works, but back then, it was an ordeal to get everything working the first time.

- The Rolling Stones may have been the first major band on the internet. In 1994, the band not only launched a website to promote its album Voodoo Lounge, it actually streamed a concert on the platform in November of that year, using an online provider named MBone for some reason. You can actually watch a video of the concert here.

- It was possible to buy stuff online before Amazon. While Amazon popularized the model of purchasing things, the online outpost CD Connection (which is still online today, albeit not in the telnet-based form highlighted in this book) made it possible to actually purchase CDs online as early as 1990.

- Newsletters were probably bigger, proportionally, than they are now. This book mentions the concept of spam, an important part of internet culture, rarely—if at all. But one thing it did highlight repeatedly were mailing lists (sometimes in newsletter form, sometimes in listserv form) for things like issues of Dilbert (A pre-pickup-artist Scott Adams actually ran the list!), or getting access to things like grant proposals, or access to local communities. It’s clear that email was a much more fundamental piece of the internet pie in the ’90s, especially compared to the modern day, where it’s still heavily used, but only one of many things fighting for your attention.

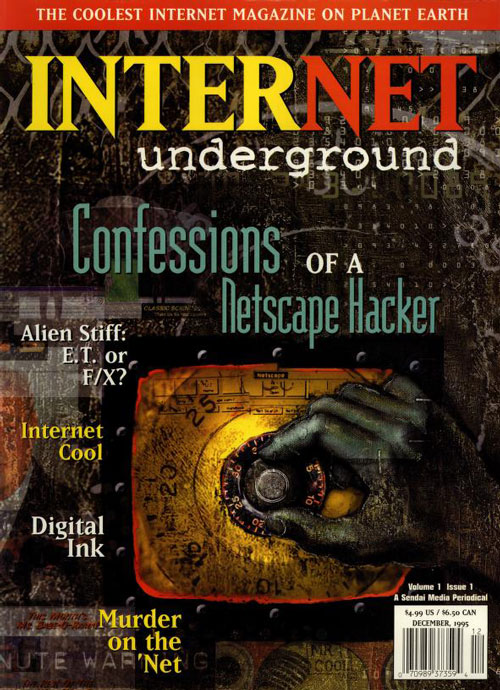

“Internet Underground was this celebration of this relatively lawless, boundless network of ideas we call the Internet. It assumed two things about its audience: 1) You were a fan [and] 2) you knew how to use it. Otherwise the magazine would haven’t have made much sense to you.”

— Rob Bernstein, the editor of Internet Underground magazine, discussing the nature of the magazine with The Kernel. The magazine, published by the same corporate parent as Electronic Gaming Monthly, was less a guide to the internet and more a dive into its culture—a rarity of its era, one that felt written for people in the know than those on the outside. Probably its best comparison point was Wired, but it felt a bit rougher around the edges, in a good way. The magazine was eventually retired and folded into Yahoo! Internet Life, which was pretty much the opposite of Internet Underground in every way. An online archive of the magazine still lingers, but a full print issue only found its way onto the Internet Archive relatively recently. (I recommend you read it, especially if you like the “grunge typography” stylings of graphic designer David Carson. It’s a trip.)

“The biggest problem is that there’s still a lot of dorks in computing,” Dan Gookin, the author of the original DOS for Dummies, told the Orlando Sentinel in 1993. “They’re the kind of people who were in chess club in high school—real bright but wound up in their self-centered little technical world, and they can’t communicate with other people.”

Now, Gookin has always been this salty—in a Dummies retrospective for Slate last year, he implied that the series’ publisher at the time, IDG, “would have wrapped that title around newsprint and it still would have sold.”

But something tells me that his point to the Sentinel in the ’90s, while sort of mean and dismissive of a whole segment of the population, is grounded in a degree of reality. The internet was not a welcoming place for strangers, of which huge chunks of the global population very much were. In early 1994, after Mosaic but before Netscape, while Adam Curry still owned MTV.com, New York Times writer Peter H. Lewis suggested that the internet seemed exciting, but that it was unwelcoming to newbies, who needed a guide to get around.

“First-time visitors may discover that finding the way around is an ordeal, especially if they do not speak the language,” he wrote.

Computer and internet reference books of the ’90s were very much that guide. They represented a kind of midpoint between sheer hucksterism and infotainment. Going back to Free $tuff From the Internet, I should point out that the structure of the book was this weird setup where every single resource got a full paragraph description, no matter how large or small it was. A link to a directory of Beatles photos on a random FTP server would get just as much text as a blurb about resources explaining the then-new North American Free Trade Agreement. Despite the fact that one probably needed more detail, it didn’t really get it.

This book, essentially, is the equivalent of one guy’s bookmark list in the days before Netscape popularized bookmarks on the internet.

Internet Underground: The coolest internet magazine on planet Earth. (via the Internet Archive)

I don’t think Patrick Vincent was trying to pad out the book by doing this. I do think that he was aiming for an audience that needed online training wheels, in comparison to Internet Underground magazine, which aimed for one that didn’t.

I loved Internet Underground magazine. I used to have every issue. That it was replaced by, essentially, the magazine version of Free $tuff From the Internet, is both depressing and fitting.

The fact of the matter is, the public needed a map in the early days of the internet. It took a while before people understood memes.

:format(jpeg)/2017/06/tedium062917.gif)

/2017/06/tedium062917.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)