How The Cookie Crumbles

Why did Hydrox cookies lose out to Oreo despite being the first cookie to market? Long story short: The name seemed like a better idea 100 years ago.

An early Sunshine Biscuits ad for Hydrox, published in the Saturday Evening Post circa 1922. (via Google Books)

An English biscuit with a little sunshine—how Hydrox was born

In the 1870s, a Kansas man named Jacob Loose got his start in building out a food empire. Opening up a dry-goods business in Chetopa, Kansas, he slowly gained influence as an entrepreneur.

After quitting dry goods, he bought a biscuit and candy company in 1882, and with his brother Joseph, he would put together a company that, after a few name changes and the addition of a partner named John Wiles, would come to be known as the Loose-Wiles Biscuit Company.

Jacob Loose was prominent enough that he had a seat on the board of a budding conglomerate called the National Biscuit Company, which started in 1898 as an early attempt to consolidate resources. But by 1902, as Loose-Wiles was getting its footing, he had divested from the company entirely—that company, later known as Nabisco, would become Loose’s largest competitor.

One of Sunshine Biscuits’ many factories. (Thomas Hawk/Flickr)

Loose’s company built baking plants that were designed around windows, and those hard-to-miss plants gave the company’s products their name: Sunshine Biscuits, which decades later would give the company its name.

A few years after the launch of Sunshine Biscuits, the company came up with the biscuit sandwich it called Hydrox in 1908—four years before the Oreo. Like the sunlight that glimmered through its factories, the name was intended to speak to a basic purity of product.

The truth was a bit more complicated, however. Intended to imply hydrogen and oxygen—the two chemicals that make up water—the result has a more clinical, less roll-off-the-tongue convention to it, and instead evokes hydrogen peroxide, a chemical you probably don’t want to drink.

And it didn’t help that that there was an existing Hydrox Chemical Company on the market, one that sold hydrogen peroxide and was caught up in a trademark lawsuit at the time over the use of the word “hydrox”—a lawsuit that noted the term was used for coolers, for soda, even for brands of ice cream.

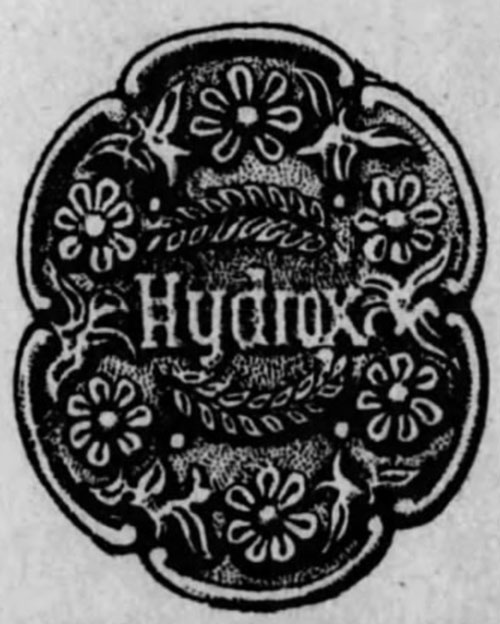

An early Hydrox cookie design. (via the Akron Evening Times)

Long story short, it was a weird name for a cookie. But the cookie’s design, which was initially sold with an exotic “English biscuit” twist, was pretty interesting for its era: With an industrial press from a mold, the cookie took on the look of a flower.

It felt like a game-changer, but it turned out to be a game-changer for Nabisco, under a completely different (and better) name. It was one of three cookies introduced by Nabisco on April 2, 1912, with the other two—the Mother Goose biscuit and the Veronese biscuit—being lost to history, but Oreo’s “two beautifully embossed chocolate-flavored wafers with a rich cream filling” living to the modern day.

But where did that leave Hydrox?

“The Oreo is a cookie that embraces contradictions. Not only is it dark on the outside and light on the inside, but it is lavishly ornate in its exterior design while being utterly simple within. In an even more fundamental fashion, however, the Oreo’s form leaps across stylistic boundaries.”

— Paul Golderberger, an architectural critic who once wrote for The New York Times, pondering the architecture of the Oreo in a 1986 article, in a way that clearly nobody else has ever pondered to this degree. Golderberger had some thoughts on the Hydrox, too. “The Hydrox’s ornamental pattern is at once cruder and more delicate than the Oreo’s; the ridges around the edge are longer and deeper, but the center comprises stamped-out flowers, a design more intricate than the Oreo pattern,” he stated. “Still, it is the Oreo that has become the icon.”

A Hydrox ad, circa 1957. (Classic Film/Flickr)

Why Hydrox was the first brand to go in the middle of all the mergers

Hydrox as a brand never really thrived in comparison to Oreo, even if the slightly-more-bitter cookie had its partisans.

Certainly the legacy of the Sunshine Biscuits factories didn’t lose its luster quite so quickly, and Jacob Loose died a rich man. (Two words: Cheez-It.) But Hydrox, once a hit in its own right, couldn’t compete with the larger brand’s more effective marketing.

That’s not to say that Hydrox didn’t have natural advantages. For example, while Nabisco was stuck spending money on a costly transformation to remove the lard from the cream in its cookies, Hydrox cookies were already kosher, which for decades gave them an advantage in the market.

The problem, when it comes down to it, may have been the name. When Keebler took ownership of the Sunshine Foods brands in the late ’90s, most people thought Hydrox was the Johnny-come-lately, when it was really Oreo that had entered the market second. And the name proved such a huge turnoff that Hydrox only had 4.2 percent of the sales of Oreo in 1998—just $16 million compared to Oreo’s $374 million takeaway.

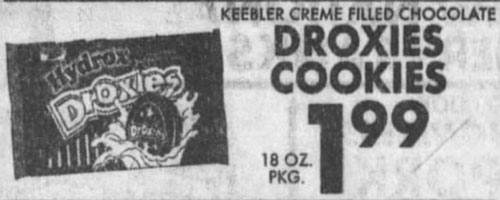

Keebler realized this was a problem and quickly attempted to rename the cookies Droxies, a sort of softening of the name to discourage people from thinking of chemicals.

A rare example of the “Hydrox Droxies” transitional packaging, used when Keebler was switching between the two brands. (via the Press and Sun-Bulletin)

“Not only does it cue back to ‘Hydrox,’ but it’s a fun, whimsical name that really works with the Keebler imagery.” Keebler marketing director for cookies Carolyn Burns explained to Fortune in 1999.

But the shift wasn’t enough; in 2001, Kellogg’s had bought the Keebler brand, putting Hydrox under yet another corporate owner, and by 2003, it had stopped selling Hydrox altogether—sans a brief reprieve in 2008 after enough consumers complained that it briefly changed its mind.

“This is a dark time in cookie history,” one Hydrox partisan, Gary Nadeau, wrote, according to the Wall Street Journal. “And for those of you who say, ‘Get over it, it’s only a cookie,’ you have not lived until you have tasted a Hydrox.”

Cheez-It sales continue unabated—complete with the tiny Sunshine logo, a reminder of a history of giant factories with glass windows.

1998

The year that many Nabisco products went kosher for the first time, including Oreos. The change was symbolic from a cultural standpoint, as it had taken a basic piece of Americana and made it available to a section of the U.S. public for the first time. “No, we don’t have a Jewish president yet, but something almost equally astounding has transpired, a telltale sign that Jews have finally made it,” Rabbi Joshua Hammerman wrote of the news in a 1998 New York Times Magazine article. “After eighty-five years in the gentile larder, Oreos have gone Kosher.” (He was more mixed on the cultural implications.) This put Hydrox at a big disadvantage.

Of course, nothing can stop a businessman with a plan and knowledge of the inner-workings of the trademark world.

And that’s why Hydrox cookies were able to make a comeback in 2015, whether Kellogg’s actually wanted them to or not. Ellia Kassoff, a Jewish kid who grew up on the kosher cookies, had gained some knowledge on how to gain access to a trademark that was sitting unused, and as a result, he was able to pick up Hydrox for his own company, Leaf Brands—itself a dormant brand that Kassoff had revived.

“You’d be surprised how many companies are hoarding trademarks,” Kassoff told The Consumerist in 2014. “In other words, to be blunt, they lie to the Trademark Office.”

He figured out that, since Kellogg’s admitted it wasn’t interested in doing anything with the cookie brand, he legally had the right to cancel the trademark and re-use it. He had to do all the hard work of reformulating the snack, but once he had figured that out, it was off to the races.

Some modern-day Hydrox cookies. (via the brand’s Facebook page)

However he did it, it’s now possible to buy Hydrox cookies once again in stores, no matter the name or the lingering arguments about brand authenticity.

Not only are the cookies kosher these days, but they’re made with real sugar and without GMOs. And even if they’ll always be the second banana compared to Oreo, they have a spot in the grocery store again.

No gimmicks here.

:format(jpeg)/2017/05/tedium050917.gif)

/2017/05/tedium050917.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)