The Sauce-Packet Squeeze

How long do sauce packets last, and can you recycle these old Heinz Ketchup packs? We research condiment packaging so you don't have to.

"I don't know what I was thinking when they said 200 case. Oh, yes I remember—a box of neatly stacked packets. Instead I got a mailing bag stuffed with a pile of packets. I can only assume that I got 200. But the ketchup is good and fresh."

— Amazon user Lois Bennington, in a review of an Amazon delivery of a 200-pack case of single-serving Heinz ketchup. She wasn't impressed with the way that the ketchup was delivered to her. Yes, you can buy bulk packets of condiments from Amazon or other online outlets such as Food Service Direct and Heinz's own food service vendor. A suggestion for Ms. Bennington for next time: Go to your nearby food court and take a couple extra handfuls with you. It might save you some money on shipping, and it's probably what the seller did with the ketchup he or she delivered to you.

Five things you didn't know about ketchup packets

- The first Heinz ketchup packet didn't come about until 1968, getting beat to the market by soy sauce packets, which came about roughly a decade earlier.

- According to Marketplace, food companies are very particular about the size of their ketchup packets. Despite the fact that they generally can be made in larger sizes, the market has settled on nine-gram packets, despite the fact that nine grams is clearly not enough since we use like six of them in a single serving.

- Heinz sells a lot of these packets every single year—according to the company, that's around 11 billion or so every 365 days, or two for every person on the planet. At nine grams each, that's about 109,000 tons of ketchup. Heinz uses more tomatoes than any other company in the world.

- While Heinz is by far the largest producer of ketchup packets, they're far from the only one. And the largest fast-food chain, McDonald's, doesn't use them—although they used to supply 90 percent of McDonald's condiments. In fact, Mickey D's announced it was severing its ties with Heinz completely after the condiment company hired Burger King's former CEO as its new chief executive. (Fast food beefs run deep, apparently.)

- Ketchup packets are generally not very easy to recycle, because they're made of a combination of plastic and foil, and separating the materials is far more difficult than fusing them together. The juice maker Capri Sun, which makes its packaging in roughly the same way, has come under fire in recent months (including in Tedium) because its packs can't be recycled.

400

(Photo by Mike Mozart/Flickr)

So … how long can a condiment packet survive, anyway?

OK, let's go back to the pile of random condiments sitting in your fridge. Clearly they've probably been there for a while, perhaps dating to the Clinton administration or longer.

These devices of saucedom generally have very little in the way of useful information located on the package. No nutritional information, and generally no expiration dates. Which might make one wonder—do they last forever?

I'm here to tell you that, in most cases, they don't. Some types of condiments commonly found in packet form, like honey, salt, and sugar, don't really go bad for various reasons.

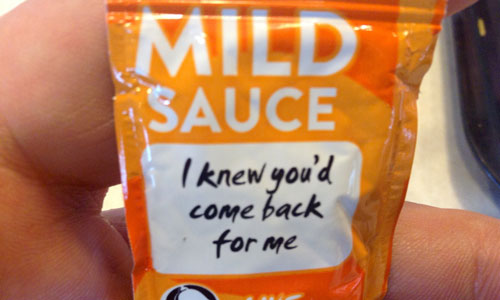

But those spare Taco Bell sauce packets that you've been using like Tabasco from another mother? Yes, they spoil. They lose their flavor over time, and those plasticky metal packets only go so far to protect the spicy flavor that's buried inside of the casing. Same with ketchup, mayo, mustard, BBQ sauce, or relish.

And believe it or not, they do actually have expiration dates generally listed—just not on the sauce packets themselves. Instead, they tend to have it on the boxes that the restaurants pull the hot sauce out of.

This issue that we're touching upon is actually a big topic of discussion in the survivalist space. It's understandable: If the world ends and you run out of sustenance elsewhere, that extra supply of Horsey sauce from Arby's is going to come in handy. But the result is a little disappointing from a results standpoint. A common story shared around survivalist forums is this one from WISN reporter Portia Young, who found that most sauces last less than a year. There's not a lot of meat there, and I'm linking to Wayback Machine link, so clearly this information is current and authoritative, but here's the list she acquired from Heinz:

- Ketchup: 7 months

- Chopped onions: 7 months

- Mayonnaise: 8 months

- Fat-free mayonnaise: 8 months

- Relish: 9 months

- Mild taco sauce: 9 months

- Hot taco sauce: 4 months

- Yellow mustard: 9 months

- BBQ sauce: 9 months

- Steak sauce: 9 months

- Tartar sauce: 8 months

- Horseradish sauce: 8 months

- Cocktail sauce: 9 months

- Tabasco sauce: 8 months

A slightly better piece of research on the issue comes from a site called the Outdoor Herbivore Blog, which puts expiration dates on the sauces and offers some guidelines as to what to expect when you're in the middle of nowhere and the only thing you have to eat is a packet of mayonnaise that you found inside the seat cushions of your 1989 Ford Taurus.

"Before consuming the condiment, inspect the packaging. If it appears puffy or is damaged, toss it. When you open the packet, inspect it. If it has an odd color, texture, flavor or odor, toss it," the site explains. "Condiments containing fats (mayo, butter) go rancid more quickly."

But on the other hand, certain types of packaging can ensure that you're getting a higher quality of extremely-dated condiment than you might elsewhere. Paper packaging might not cut the mustard, but that foil/plastic contraption that can't be recycled might actually come in handy in case of a zombie attack!

“The recession taught fast-food restaurants that you must run a much more efficient operation. You must run a tight ship, and you cannot get by being loosey-goosey and freewheeling with your condiment packets.”

— Sam Oches, editor of QSR, a fast food industry trade magazine, discussing with Slate the recent decision by some fast food locations to start putting hot sauces behind the counter, only handing one or two out at a time. The issue makes sense from a financial perspective, based on the saga we pointed out earlier about the guy with trash bags full of Taco Bell sauces just sitting in his car. Oches later told Slate contributor Ruth Graham, who wrote a whole story about restaurants putting sauces behind the counter, that there's an element of behavioral psychology at play. “Ultimately if you start to implement some of the change at the store level, where you switch the expectation from not getting to grab handfuls of condiment packets and have to go up to the counter to ask, in time people will forget,” he explained.

Now you may know that when you go to a sushi bar, you're not actually being given real wasabi, but rather colored mustard and horseradish. We can all live with a little deception in our lives.

But there's a much bigger deception hiding in your hospital-cafeteria sushi package: the soy sauce isn't actually soy sauce.

In an important work on the level of anything Ta-Nehisi Coates has written for the magazine, The Atlantic contributor Tanya Basu last year wrote a story about the history of the plastic soy sauce packet that, to put it modestly, is a tour-de-force in the world of condiment journalism.

The story pointed out a couple of unbelievable truisms about portable soy sauce: Howard Epstein, a Jewish man from the Bronx, played an important role in the creation of soy sauce packets; Epstein used his knowledge of producing freezer pops in deciding on the basic shape of the packets; and they came about essentially as a way to offer Chinese food on airplanes. Important stuff.

Thrillist, having seen the article, used the article's buzz to point out a disgusting, disappointing fact that you didn't notice: those soy sauce packets quite often don't include soy, but instead a reassuring ingredient called "hydrolyzed vegetable protein."

Everything we know about soy sauce is a lie.

:format(jpeg)/2018/01/rywfqohncf5xzadg17ld--1-.gif)

/2018/01/rywfqohncf5xzadg17ld--1-.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)