The Game Genie Generation

For an unlicensed game accessory, the Game Genie sure casts a long shadow. It reshaped the games we already owned—and had a profound effect on copyright law.

“We didn’t have a license to create Nintendo games so we found a way of bypassing Nintendo’s lock-out chip and released games that way. We had an idea of placing a switch on the cartridge to add extra lives, weapons, and things like that. Then we made the mental leap of saying that if we could do this with our own games, then maybe we could build an interface for other people’s games too. It was a game that morphed into an industry.”

— David Darling, one of the founders of Codemasters, the British gaming company that first created the Game Genie in the late 1980s, discussing how the device came to be in a 2015 interview with the now-defunct GamesTM. Darling, who produced dozens of games over the years—most notably the Dizzy series—eventually licensed the idea to Galoob, a major American toy company that started selling the NES version of the device in mid-1990. They eventually turned the hacky device concept into a $140 million cottage industry. For creating the Game Genie and helping develop the British gaming industry, David Darling, along with his brother Richard, were made Commanders of the Order of the British Empire back in 2008. See, even the queen noticed!

The appeals court case that legalized the Game Genie was recently used to claim that Anthropic’s LLMs are fair use

The idea of a video game console like the Nintendo Entertainment System is that it’s a console, not a computer. In a perfect world, you’re not supposed to see the wires holding together the games.

But the Game Genie exposed them to the world, in batches of six or eight characters, and that made the device both dangerous to Nintendo and extremely appealing to your average eight-year-old.

Of course they were going to butt heads over it, and it feels like a situation that, one look at the legal battle between the two, has a lot of modern parallels. In fact, the legal battle between the two companies was recently cited in a landmark appeals court ruling involving the LLM provider Anthropic.

Yes, we live in a world where we can directly compare Claude siphoning the whole of human knowledge with the six- or eight-character codes you put into your NES in 1991.

The saga began in May 1990, when the device’s U.S. distributor, Lewis Galoob Toys, sued Nintendo, seeking declaratory relief against Nintendo, in hopes that a court could tell them the Game Genie was safe to sell. It was not clear if Galoob would win, and at first, they didn’t.

(It should be noted that another way this story has relevance to the modern day is via trade. See, while the Game Genie was temporarily banned in the U.S. because of the lawsuit, it had gone on sale in Canada, where a separate legal battle quickly fell out of Nintendo’s hands. If you knew someone going to Toronto, it was presumably easy to get one across the border. It wasn’t like this device was contraband.)

The early rounds of the case did not go Galoob’s way, with a preliminary injunction preventing the device from being sold. But like a quick-witted Micro Machines pitchman, Galoob ultimately got the last word in: The federal district court eventually favored Galoob’s stance, and when an appeals court decided to take the case on in 1992, it was bad for Nintendo.

In his decision, Joseph Jerome Farris found that slight modifications of a derivative work were allowed, as long as the original form of copyright was kept intact.

“The Game Genie merely enhances the audiovisual displays (or underlying data bytes) that originate in Nintendo game cartridges,“ the legal decision states. “The altered displays do not incorporate a portion of a copyrighted work in some concrete or permanent form.”

The ruling created a pliable standard for derivative works.

Very quickly, the ruling became an important one in the history of fair use. It also raised some legal precedent regarding whether Galoob could get money back for all those lost sales caused by the injunction. (Nintendo had to pay them damages!) Ever think, as a non-lawyer, that when a plaintiff or defendant loses a preliminary injunction, that’s a great sign they lost their case? Galoob is clear evidence that is not always the case.

Almost immediately, the ruling was cited in a separate case that pierced the armor of the Sega Genesis’ first-party developer arrangement. It was a significant win for fair use in relation to emerging technology.

But the ruling long outlived the relevance of its hardware. It is frequently cited both for its precedent related to bond damages for a victorious company that lost in preliminary rounds, as well as what it had to say about derivative copyright.

/uploads/Screenshot-From-2025-07-21-14-15-07.png)

Which is why, when the recent federal court ruling came about in Bartz v. Anthropic PBC, it cited Galoob. For those who haven’t closely kept an eye on the LLM case, the gist of the ruling was that Anthropic was found to be liable for stealing millions of books by downloading them online. However, had it gone to the trouble of buying those books, it would have been fair use as the use case was suitably transformative.

Essentially, it erred by not buying legal copies of every book it used to build Claude. (It did buy and digitize some copies, and the case makes it sure feel like, if you know anything about the Internet Archive lawsuit, the Internet Archive should have just built an LLM instead of a digital lending library.)

“That the accused is a commercial entity is indicative, not dispositive,” the Anthropic ruling states. “That the accused stands to benefit is likewise indicative. But what matters most is whether the format change exploits anything the Copyright Act reserves to the copyright owner. Anthropic already had purchased permanent library copies (print ones). It did not create new copies to share or sell outside.”

This, per the ruling, parallels the way that Galoob hinged on the fact that the Game Genie was fair use because no additional copies of the cartridge were created by using the device. (The Anthropic case uses the phrase “nifty converter” to describe the Game Genie, which I’ll allow.)

“As a result, Anthropic’s format-change from print library copies to digital library copies was transformative under fair use factor one,” the ruling continued.

It’s a weird connection, but it’s one that absolutely makes sense. You may not love LLMs or love that this was one of the things that a key copyright case involving LLMs hinged on. But the Game Genie, as a device that transformed an existing work, is certainly what you want to point to if you’re trying to defend the existence of something like Claude.

Sponsored By Jack & Jill

Jack & Jill—The world's first AI recruiters

The job search is broken. Endless forms, ghosting recruiters, and spammy pitches aren’t just annoying—they’re a waste of time.

Jack & Jill fix that. They’re AI recruiters—not chatbots, not job boards. Real AI agents that screen roles, interview candidates, and match people with companies.

Jack helps candidates:

- Speak with him once

- Get matched to top jobs

- Skip the noise

Jill helps companies:

- Source and screen talent

- Shortlist only the best

- Offers intros to the best candidates

No cover letters. No ghosting. No agency fluff. Just real matches, fast.

Thousands of people are already getting hired through Jack & Jill.

Let AI do the boring parts—so humans can make better decisions.

Are you looking for the perfect job or the best candidates? Speak to Jack & Jill.

$15M

The amount Nintendo ended up having to pay Galoob for a year of lost sales due to their copyright infringement lawsuit against the company, according to a 1994 ruling on the case which found that the company lost this amount—or more—due to the fact that they couldn't sell the device at the height of the NES’ success. "While it is true that Galoob did not likely lose exactly 1.6 million sales of the Game Genie, it is reasonably certain it lost at least that amount," the 1994 Ninth Circuit ruling stated.

In case you want an explanation of how Game Genie codes actually function on a technical level, I recommend this relatively recent clip from Modern Vintage Gamer.

Five of the Game Genie's many unusual quirks

- On the NES, the Game Genie gave an already quirky horizontal cartridge-loading mechanism a little extra trouble. The silicon on the device bent the console's pins, which eventually meant that if you used it too much, your console wouldn't work without it.

- The Game Boy version of the device was freaking huge, with a ton of extra plastic. And because the device stopped being made around the mid-1990s, that meant no newer versions came out, making it downright impractical to use with any Game Boy besides the original. It does work, as this dude using a Game Genie on a Gameboy Advance SP proves.

- The Super Nintendo version didn't work with games that had built-in performance-enhancing chips inside the cartridges, at least at first. Sucks if you're a Starfox fan.

- Unlike Nintendo, Sega backed the Game Genie, making Galoob an official licensee of the company. Sega, however, required the Genesis version of the Game Genie not to be compatible with games that had built-in save functions, such as Shining Force.

- On the Sega Game Gear, if you typed in the code "DEAD," the screen would bounce. Because honestly, why not?

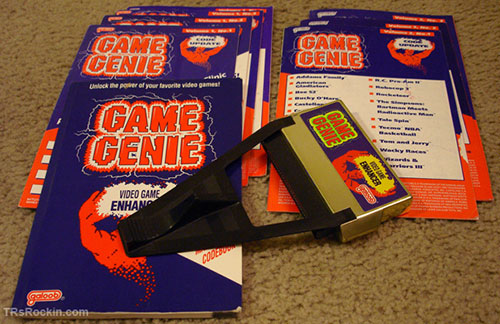

The Game Genie and its many manuals, some of which were sent to customers as supplements.

Gaming culture benefited deeply from the Game Genie precedent

One could imagine that the people working on modern gadgets now were playing video games with Game Genies in the early ’90s. And they likely found something inspiring about how easy it was to go off-script.

It made it possible to remix games, to poke at details and see how broken the resulting game would be. Galoob gave you a book with codes that they verified to work.

Those codes did a lot. It suggested that that these things we experience didn't have to be used only one way. Mario didn't necessarily have to jump in one direction—in fact, he could jump backwards, live unlimited lives, and have all the firepower one could ever need. This was crazy talk, the stuff of fantasies!

But it was the off-label uses of the Game Genie that made it interesting. It was like taking random drugs and seeing what they did, except (instead of making you sick or drowsy, or worse) the only damage it would actually create is that it would bend the pins on your NES so it didn’t work as well later on.

As an ten-year-old, I would spend hours putting in random codes, or modifying existing codes in the book, to see what it would spit out at me. Sometimes the codes would create utter gibberish on screen; other times, they would offer powers that you would never be able to find in the regular game.

I know of at least one popular YouTuber, gruz, who focuses on these off-label concoctions. He has a whole playlist of these things. The one above shows him playing a version of Super Mario Bros. with the code SIAGEO, which makes all enemies throw hammers and jump around like Hammer Bros., even fire flowers.

(One imagines you could have a pretty good career on Twitch just putting random Game Genie codes in random NES games just to see what happens.)

The fact that the Game Genie came along at this particular time, when the Nintendo Entertainment System and Sega Genesis libraries mostly consisted of relatively simple games, was part of the appeal. It was the best possible evidence that the technology around us, like words and art before, is brittle and malleable. That other people's creativity can be changed.

At the time the Game Genie came out, remix culture was all the rage. Paul’s Boutique had been out for a year, and “U Can’t Touch This” (which essentially put one guy’s extremely repetitive raps wholesale over another dude’s song) was dominating the airwaves. Meanwhile, you couldn’t walk outside without seeing dozens of knock-off Bart Simpson T-shirts.

Original creators, like Nintendo, didn’t like this because it jeopardized their control over the end product. But the culture seemed happy to want the final product to morph in whatever way they could think of.

In a lot of ways, the ability to type in codes to tinker with the way that a game worked was akin to being a grease monkey or HAM radio operator in an earlier generation. Once you figured out there were these codes that could change, and that the little booklet was only the starting point for what was possible, suddenly a ton of opportunities arose.

When HTML, PHP, and JavaScript became the lingua franca of the internet a decade later, a lot of those coders probably cut their coding-mindset teeth not on BASIC, but on Game Genie codes. The Game Genie even helped inspire a fairly strong glitch-gaming culture that persists to this day.

While other devices could do what the Game Genie did—the later GameShark eventually took its crown as the cheat device to beat—it was the Game Genie that regular people remember, because it represented a shift in how we thought about tech.

Now, we remix everything, whether a company wants us to or not. It’s just how we’re built.

In a way, it’s kind of fitting that I get to cite a case like Bartz v. Anthropic PBC in a story about the Game Genie, because it’s clear that LLMs kind of represent a modern version of the sort of weird hackery that we used to do around Game Genie codes.

The idea that you can make weird photos, or have Claude or OpenAI recite to you bawdy poetry, or attempt to build you a theoretical web server for you based in the long-dead QBasic programming language, scratches the same sort of itch. On the surface, it seems like they work very differently—after all, generative AI’s whole pitch is that it can sell you ideas made from whole cloth. (It’s a lot more controversial than using a Game Genie ever was, that said.)

But the Anthropic lawsuit lays bare the truth: This information all came from somewhere. The difference is that you didn’t buy all those books and remix them into something useful. Anthropic did. (Well, at least, some of them.)

These days, Nintendo has found new ways to limit the upside for using devices it doesn’t like. The Switch 2 reportedly does not follow USB-C specifications, blocking hardware it has not explicitly approved, and the company actually blocks users from online access if they share games in an unauthorized way. (The EU is not going to like that first one.)

Codemasters and Galoob felt the brunt of this back in the day—the Game Genie developer was arguably the best unlicensed NES developer, and their best game was based on a Galoob product. But despite Codemasters’ obvious skill and the sheer joy that a Dizzy game gives me, they were locked out of traditional avenues, all because it built the Game Genie.

So, Nintendo doesn’t play fair, and 35 years later, not much has changed there. But in 1990, the company took a harsh stance—and lost a big one. And the way it lost that one reflected the culture it was in. The difference between then and now is that we have a lot of alternatives in case we decide that Nintendo’s version of hardball isn’t the game we want to play.

The Game Genie is the culture I want to see.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal! And thanks to Jack & Jill for sponsoring this one!

:format(jpeg)/uploads/tedium072125-1.gif)

/uploads/tedium072125-1.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)