New Verse, New Story

There was a certain type of song that seemed to keep cropping up in the mid-’90s. Here’s my attempt to figure out why that was.

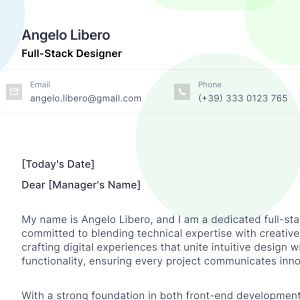

Sponsored By InterviewPal

Write Smarter Cover Letters: Tired of copy-pasting the same awkward intro? This tool helps you write tailored cover letters using AI, without sounding like it was written by one. Job hunt like it’s 2025. Click here to learn more.

/uploads/mmmmmmmmmmmm.jpg)

The elements that defined the ’90s story song

Story songs are nothing new, as anyone living in the ’60s and ’70s could tell you. Songs like Harry Chapin’s “Cat’s In The Cradle,” Don McLean’s “American Pie,” and Arlo Guthrie’s “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree” told winding, episodic, sometimes complex stories across numerous verses, and were often more about the plot than the chorus.

The ’90s had songs shaped like these, too. “Jeremy” by Pearl Jam is essentially that decade’s version of “Cat’s in the Cradle”—apologies to Ugly Kid Joe, whose own version of that song was charting around the same time as “Jeremy.” I’m sure you could go way back to the history of the ballad and find lots of examples of songs that fit this form.

But during the 1990s, an interesting variation of the song started to find its place on the pop charts: The tune that told multiple self-contained stories in the span of just a few minutes.

These stories largely don’t reference one another, and are mostly third-person in nature. They are episodic, and brought together not by a first-person protagonist, but by a single theme, often carried by the chorus.

The perfect example of this format came from Canadian folk-pop band Crash Test Dummies in 1993. In retrospect, “Mmm Mmm Mmm Mmm” is not a well-loved song. But its simple, memorable structure proved catnip to mainstream radio. Beyond the wordless chorus, it was essentially a three-act play in song form—telling the stories of three different school outcasts.

The first two had physical ailments—a boy who had white hair after being in a car accident, and a girl covered in birthmarks. The ailment the third faced, described as “worse than that”? He grew up in a hyper-religious household and went to a weird church. While not stated in the song, the lyrics explicitly describe a Pentecostal church: ”And when they went to their church/They shook and lurched all over the church floor.”

And fittingly, these situations lent themselves perfectly to a music video.

The video adds subtext to these stories—a pair of parents clearly upset about getting called out for their hyper-religious parenting style is a specific standout—but essentially, we are watching the plot of the song portrayed literally.

This kicked off a subtle trend of pop songs seemingly built with visual imagery in mind—a trend immediately exploited by one of the biggest girl groups of all time.

In the summer of 1995, TLC dominated the airwaves with the self-contained cautionary tales that make up “Waterfalls.” The song borrowed a lyric from a Paul McCartney tune of the same name but quickly superseded it in influence.

It wasn’t all cautionary tales, however. In the bridge/third verse, Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes uses the song’s subject as a way to address her personal problems at the time, which included an arson arrest after setting her boyfriend’s house on fire. She uses the moment to contextualize the song’s deeper message:

Who’s to blame for tooting ‘caine into your own vein?

What a shame, you shoot and aim for someone else’s brain

You claim the insane, and name this day in time

For falling prey to crime

I say the system got you victim to your own mind

Dreams are hopeless aspirations in hopes of coming true

Believe in yourself, the rest is up to me and you

Around the same time “Waterfalls” was blowing up, Live’s “Lightning Crashes” was having a moment of its own. A circle-of-life in which birth and death take place in different verses.

The song essentially deals with three generations of people—a mother giving birth, a new child, and an older woman dying in a nearby hospital bed. The third verse loops back to the first. It was easily the biggest hit of Live’s career, and helped cement the band as one of the era’s most popular—though singer Ed Kowalczyk often speaks of the song’s popular video creating misinterpretation around the song. (It probably doesn’t help that the video shows a young woman dying, when the song itself says old woman, as it makes it look like the woman died in childbirth.)

If “Mmm Mmm Mmm Mmm” is the purest expression of the three-act play in pop song form, the second-purest perhaps came from Everlast. In 1998, the onetime House of Pain rapper became something of a hip-hop troubadour, offering his own take on a “Waterfalls”-like song with his solo hit “What It’s Like.” That tune is a classic walk-a-mile-in-their-shoes song, to the point where it literally says that line in the chorus.

It tells the story of three protagonists—a homeless man, a pregnant woman who chooses to get an abortion, and a drug dealer who dies in a fight. The music video visually displays these stories, but at the end of the video, it shows a group of people looking, outside-in, at a storefront.

What’s on the other side of the glass? A normal family that doesn’t have any of these problems. Not exactly a subtle metaphor.

If you wanted to stretch the definition somewhat you could find more interesting examples that fit the mold. The Offspring had multiple singles off its 1998 album Americana that played with this basic model. “Why Don’t You Get A Job,” explicitly evoking The Beatles’ “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” told separate stories—one of a guy, and one of a girl—with deadbeat partners.

And elsewhere on the album, the more serious “The Kids Aren’t Alright” attached numerous negative outcomes to a single street with the use of multiple individual life stories told over the span of a single verse. (Word of warning: The visual effects in the video are super-dated.)

The Flaming Lips’ “She Don’t Use Jelly,” while clearly absurdist and not a message song, fits this format well. And The Pharcyde’s “Passin’ Me By,” which predates “Mmm Mmm Mmm Mmm” by a few months, is essentially a series of anecdotes about failed school crushes, with a first-person take on this general lyrical structure. And while not exactly built around standalone verses, Eminem’s “Stan” clearly gets a lot out of its vignette-driven structure.

Why this specific form, and why is it largely contained to this specific era? My feeling is that they were, in one way or another, intentionally or not, built specifically with a music video in mind.

Does this format exist just because of music videos? That kind of the thought that was racking my brain.

11

The number of separate self-contained stories in the Alanis Morissette song “Ironic.” For those keeping track, that’s three in the first verse, one in the second verse, four in the third verse, and three more in the chorus. Turns out, you can tell a story, start to finish, in a single lyric—though admittedly some might argue a story that short might be an anecdote.

Your periodic reminder that Prince was decades ahead of everyone else, based on the fact that every major artist now releases videos like this.

Five more examples of the standalone verse format that aren’t from the ’90s

- “Penny Lane,” The Beatles: When I brought this topic up on Bluesky a few weeks ago, many people thought of “Eleanor Rigby” as a key example of this song format. But looking at the structure, “Penny Lane” is a better fit, as it takes a tour through the Liverpool street near where Paul McCartney grew up, vignettes aplenty. And yes, there’s a video.

- “Walk on the Wild Side,” Lou Reed: This is a surprisingly pure example of this format. Reed, in describing the various characters from Andy Warhol’s Factory scene like Candy Darling and Joe Dallesandro, paints a broader picture by zooming in on the characters.

- “Slip Slidin’ Away,” Paul Simon: Simon’s writing style actually seems to default to the standalone verse format sometimes. (See “You Can Call Me Al” and other songs off of Graceland.) But this 1977 number, made up of vignettes with a man, woman, and a father and son, is probably his best example. The stories are only implicitly connected, but seem to tell the tale of a divorce and its impact.

- “Sign O’ the Times,” Prince: You can’t claim this fairly experimental Prince number was just shoving in stories for the verses just for the music video. See, the music video is essentially the 1987 version of a lyric video.

- “Ain’t No Rest For The Wicked,” Cage the Elephant: Over time this format has become somewhat less common in a traditional rock context, but it does still appear from time to time. Cage the Elephant’s 2009 breakout hit portrays the song’s protagonist walking down the street and being presented with ethically questionable situations. It only kind of recreates the lyrics in the music video.

/uploads/28715540128_82c188b9ee_c.jpg)

Thinking bigger picture about story songs: The secretly weird state of the first-person tune

Obviously, this lyrical format was not exactly limited to the mid-1990s. If you squint enough you can arguably see it in unexpected places. The surrealism of The Doors’ “Riders on the Storm” could feel like it’s made up of standalone verses, for example, though I would argue it isn’t.

But during the ’90s, this verse structure felt kind of like a meme for whatever reason, sort of that decade’s version of the millennial whoop. By that time we were used to musicians talking about themselves in many songs, so it was interesting to hear a character portrait like Jewel’s “Who Will Save Your Soul” on the radio.

But I guess that my bigger question is really—why did this song type seem to blow up in the mid-1990s? I reached out to a pal of mine, Chris Dalla Riva of “The Death of the Key Change” fame, for his thoughts. He suggested thinking about this from a bigger picture—which is that songs based on the individual singing might be the cosmic aberration, not the other way around.

“For literally centuries, songs weren’t associated with specific people because they weren’t recorded,” he explained. “When a song would get popular in the 1700s, it was spread by multiple performers simultaneously. Because of that, many popular folk songs were story songs. The composer, if there were one, was very foreign to the listener.”

There are many examples of what Chris is talking about here—most notably the broadside ballad, a form of lyrical or poetic ballad, dating to the 16th century. These ballads were effectively shared widely on cheap paper and then performed by randos at any nearby pub. Not exactly a prime environment for the next Bruce Springsteen to appear.

There’s a whole history about it that I won’t dive into in too much depth here—Atlas Obscura has us covered—but the basic idea is that we couldn’t associate these songs with any one person. And that put the pressure on the song, not the singer, to sell the message.

But the rise of recorded music suddenly meant that we could make that association, and as music increasingly became an artistic form, the songwriting began to look inward. In the span of a decade, music went from highly polished to highly individualistic. It suddenly mattered who sang and performed the songs.

For whatever reason, we rolled back pretty heavily to story-driven songs in the 1990s, many driven by social commentary and vignettes. And probably music videos, too.

“These songs in the 1990s stand out because they seem to harken back to something much older, something not focused on the ‘I, me, mine’ of it all,” Dalla Riva says. “Because we love to interpret everything as being inspired by the artist’s life, these songs stand apart for the distance the artist seems to have from the narrative.”

To be clear, we didn’t entirely take the musical gaze off our navels during the ’90s, a period that gave us Midwest emo, perhaps the most navel-gazey music of all. But if all these pop stars or prospective pop stars were writing songs specifically knowing that the lyrics would make for a good music video, it’s a nice happy accident—one that we should do again.

Given that Taylor Swift bought her masters back this week for, presumably, a sum of money more than the GDP of many nations, it’s worth considering her relationship with songs that weren’t really about her.

Her whole thing is writing about herself, so it doesn’t happen very often. But tellingly, the best example might have been on one of the first songs she released after her masters battle with Scooter Braun bled into the public eye.

“The Last Great American Dynasty,” the third track on her 2020 record Folklore, tells the story of Rebekah Harkness, a prominent philanthropist who became one of the wealthiest people in the U.S. after her second husband, William Hale Harkness, died prematurely. William, also known as Bill, was an heir to the Standard Oil empire, and Harkness, just shy of 40, was now in a position of unusual wealth.

Why does Swift care about this old-school socialite? Well, she bought one of Harkness’ Rhode Island homes in 2013, and Harkness had a reputation in the local community as being a rebellious outsider who bought her way into a ritzy seaside town. So, she wanted to draw the parallel between Harkness’ public perception and her own.

Swift is known for her solid inner monologue, but there’s something beautiful about her singing about someone else for an entire song and pointing out that many of the complaints about this other person could be applied to her. She has the F-you money to ignore the haters, just like Harkness did.

Swift is coming at this from a wildly different perspective than many of those ’90s artists were. Nowadays, parasocial relationships put the focus much more on the artist and the story they’ve built around themselves, rather than an individual song. Compare that to the music industry of the ’90s—where the song often mattered most, where most people probably weren’t even aware that Crash Test Dummies had more than one song on the Hot 100. The way that band, the furthest thing from Taylor Swift I can think of, had to sell themselves was with their message, and yes, their videos.

If this is what she does when she turns the lens onto someone else, she should do it more often.

--

Thanks to everyone who chipped in on my Bluesky thread a while back when I asked about this song format, as well as to Chris Dalla Riva, who had a ton of smart thoughts on this topic!

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal! And thanks again to InterviewPal for sponsoring.

:format(jpeg)/uploads/tedium053125_updated.gif)

/uploads/tedium053125_updated.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)