When the Training Wheels Decide

Yeah, yeah, as Allen Iverson once put it, “We talking about practice!” But new tech can make athletes even more valuable during the game. It could even impact your job.

Sponsored By Tech Brew

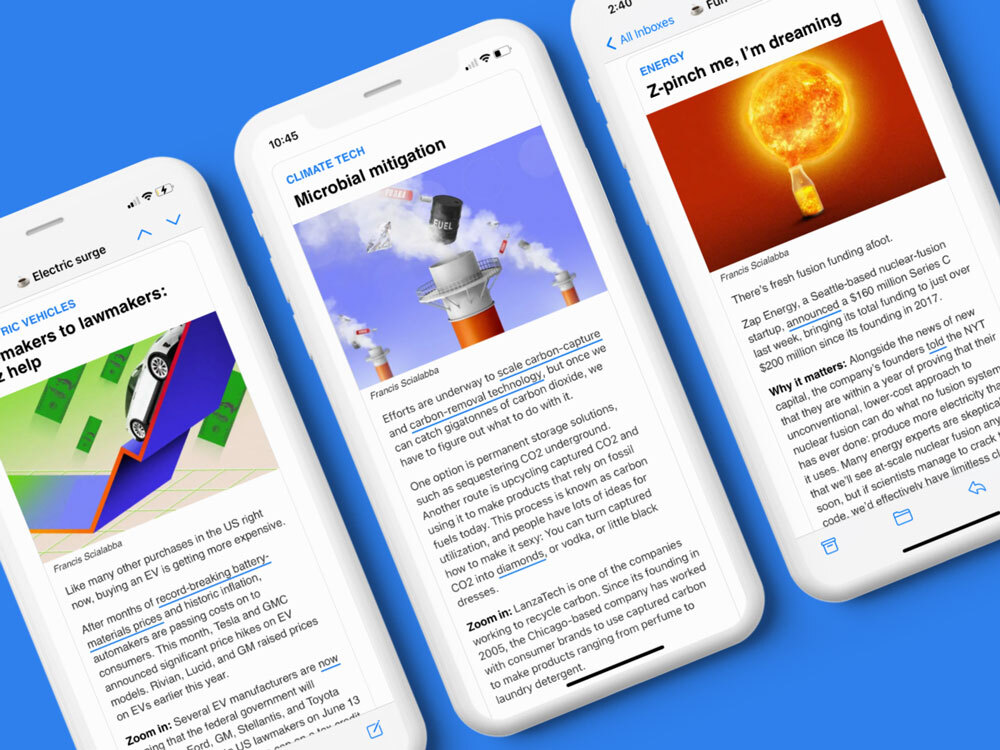

Tech news is confusing—so we changed that.

Join over 450K people reading Tech Brew—the 3-times-a-week free newsletter covering all updates from the intersection of technology and business. We provide free tech knowledge that’ll help you make more informed decisions.

[button]Subscribe For Free[/button]

24,368

Number of points scored by Allen Iverson over the course of his 14-year NBA career, the 27th highest total of any player all-time. This works out to 26.7 points per game, which places him 8th all-time in that category. Dubbed “The Answer” as a young player, Iverson was brash and cocky and nothing short of dazzling to watch on the court. Unfortunately, he might be better known for some things he said about practice.

The concept of training for sports is relatively new

On May 7th, 2002, All-Star Philadelphia 76er point guard Allen Iverson sat behind a microphone to give a press conference and said something that would become legendary.

“Practice? We talking about practice! And not a game!”

During his roughly 30 minute appearance, Iverson said the word “practice” 19 times in two minutes as he vented his frustrations over media questions about his work ethic. Some media, and even his own coach, claimed Iverson was drunk. Iverson flatly denies this. Iverson was in an emotional state for a couple of reasons. His team had been eliminated from the playoffs. More importantly, a year prior Iverson’s friend Rahsaan Langford was murdered and the trial of the killer had started just a few days before. One can be forgiven for not placing the highest priority on practice in the moment.

Whatever the cause, the Practice Rant became a sensation.

Rich Eisen, a pretty well known talking head, recounted the event in a 2021 interview with Stephen A Smith, another pretty well known talking head and friend of Iverson: “Well, I remember his practice rant … it happened just right around dinner time. Right around 5:30, 6 o’clock. Blew up the whole 6 o’clock eastern SportsCenter. That was the entirety of that SportsCenter.”

Skip Bayless, perhaps one of the most odious but influential figures in sports media, called Iverson’s press conference, “… either the most famous or infamous soliloquy ever delivered by a professional athlete.”

(As an example of his odiousness, by the way, Bayless once made waves, arguably his first foray into national prominence, by speculating on the sexuality of a Dallas football player in the 1990s.)

Fans and the media eventually came to view the ‘Practice Rant’ as reflective of Iverson’s combative, cocky, and uniquely charming personality. Unfortunately for Iverson, and to his stated regret, it is about as well remembered as anything he achieved on the court in his hall of fame career. Even Stephen A. Smith has said as much.

The questions of dedication that led to the Practice Rant are common themes for the people who talk about sports for a living. Less than total dedication is considered a cardinal sin. Which makes sense for the actual games that determine a team’s outcome. But if we’re talking practice, how much better do you realistically expect Allen Iverson to get? And when did practice become so important for athletes?

Surprisingly recently, it turns out. Sure, athletes have practiced their sports outside of competition since the creation of sports, but practice as a professional responsibility is a modern creation. Hall of Fame hockey coach Roger Neilson first introduced off season training to the NHL in the 1960s. Spring training has been a part of baseball nearly from its beginning in 1869 with northern teams traveling south to “sweat out the sins of winter in the warmth of the sun”. While teams trained before seasons began, the regular practice that Iverson was complaining about wasn’t as regular. During the season, competition tends to be regular enough to make additional strenuous practice potentially ruinous to an athlete’s health.

This kind of makes sense, as sports historians generally agree that sports developed to be practice for more practical activities like hunting or warfare. Spear throwing was the first documented competition. The only event at the first Olympics was a simple foot race. When leisure time increased enough for average people to make professional sports viable as an entertainment option, athletes were in a similar position as theater actors or musicians. Jazz drummer Buddy Rich, considered an all-time great at his instrument, notoriously never played away from the stage and a paying audience. Sure, they might need to rehearse, but the additional practice isn’t going to make them any better.

This might sound like the gripe of a guy in his mid-30s that is still salty about his parents dragging him to soccer practice. Fine, I accept that, but there really is a difference between elite level professionals and the rest of us. And yet, with significant advances in the technology used to train athletes, maybe the rest of us could train enough to achieve an elite level of performance. If only the rest of us could afford access to that technology.

$4,395

The cost for a BP3 Baseball Pitching Machine with Changeup, made by Jugs Sports. Invented by a former semi-pro baseball player in 1971, the Jugs machine, named after an old term for a curveball, would actually have a big impact in a completely different sport: football.

/uploads/JUGS-machine.jpg)

A look at the ridiculously expensive tech helping elite athletes redefine elite

Mike Piazza is a Hall of Fame baseball catcher. He also has the unusual distinction of getting to play professional baseball solely due to family connections. Piazza’s very wealthy father was friends with legendary manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers Tommy Lasorda. As a favor to the elder Piazza, Lasorda drafted Mike in the 62nd round of the 1988 MLB draft. He was the very last player selected.

Players selected that late in the MLB draft have a hard time making an active team roster, let alone going on to a 16-year Hall of Fame career. He also did it as a catcher, a position he hadn’t played before being drafted and, by all accounts, wasn’t especially good at. But Mike Piazza could hit the ball, and could so with tremendous power. As the son of a wealthy used car salesman, Piazza grew up with a batting cage in his backyard. He even received personal hitting instruction from Hall of Famer Ted Williams, one of the best hitters the sport has ever seen. And at the age of 11, his father even got him a Jugs machine.

Maybe Mike Piazza’s reputation as the child of a wealthy baseball fanatic hurt his initial chances of being scouted. Vince Piazza had attempted to purchase an MLB franchise several times. Mike received no offers to play college baseball and wasn’t considered by anyone but the Dodgers. He certainly had talent and family connections. Did early access to advanced tech help transform Mike Piazza into a Hall of Famer? His dad certainly thought so.

An excellent overview of Piazza’s early life with Cigar Aficionado, includes this fascinating tidbit:

“When I got to be 11 he said, ‘Do you really want to do this seriously?’ I said ‘Yeah.’ He said, ‘If you do, you have to practice.’ So that is when he got me the cage, and the JUGS machine, with an automatic feeder. The machine was rigged so that pitches came out every six seconds.” The machine spit out hard stuff, but inexplicably floated up the occasional knuckler. “Eventually we added a roof on it,” Piazza says, “and a heater.” The contraption was so enormous that it attracted a zoning inspector, who asked what it was. “It’s my son’s ticket to the big leagues,” Vince snapped.

Jugs machines and other types are now common tools for baseball players at all ages, but more readily available at the professional and college levels than youth organizations. Unless a parent of means tends to the obsessive, and of course that never happens.

Oddly enough, Jugs Sports owner Butch Paulson (whose dad invented the machine for him to use) kind of downplayed his company’s product when discussing its effect in a 2016 interview with ESPN, “Those guys are gifted athletes; they work so hard to become the players they are. But obviously the machine has given them a tool to develop their skills to where they are. Yeah, I guess we take a tiny bit of credit.”

ESPN took a different view, with writer Greg Garber headlining his article, “Jugs Effect: the machine that changed football”. Jugs machines are now mandatory for elite wide receivers and cornerbacks, with ESPN noting the effect has “trickled down” into college programs and some high schools. The company has also sent 100 machines to Australia for use in Aussie Rules Football.

While expensive, Jugs machines aren’t especially high-tech, or even complicated. Also, it’s a proper development tool. You can evaluate a player’s performance. For example, here’s Odell Beckham Jr being absolutely ridiculous:

As training tools involve more direct technology, they shift from pure player development, like with the Jugs machine, to player evaluation, like with radar guns. An interesting aside fact, one of the first radar guns modified for use in baseball was made by John Paulson, inventor of the Jugs machine.

Radar guns have been used in professional baseball going back to the early 1970s but the tech was limited. At this time, radar guns weren’t especially accurate, often having a margin of error around 3 mph. Early adopters of the technology saw radar guns “as most valuable for making sure there was a big enough differential between a pitcher’s fastball and his changeup… as a useful tool to help determine whether a pitcher was tiring.”

This would change. By 2014, veteran baseball scout Art Stewart told Bleacher Report, “I think any old-time scout would tell you that we’re caught in an age of just asking, ‘How hard does the guy throw?’”

That Bleacher Report article, titled “The Radar Gun Revolution”, notes that baseball has a divided opinion on the reliance on raw readings like velocity in evaluating players. One pitcher pointed to a former teammate, Koji Uehara, as someone who didn’t throw the ball with a lot of velocity but still managed to achieve a low ERA. Uehara is now retired, and his career ERA of 2.66 is nothing short of excellent.

Data-based collection tools are incredibly appealing to the people who evaluate athletes. The annual fawning of measurables during the NFL Combine, where prospective draft picks are weighed, measured, and asked to perform feats of strength, agility, and speed, is quite disturbing without context. New measurables are gaining traction in evaluations, especially of quarterbacks, with things like the Wonderlich intelligence test, and, of course, the velocity of passes.

So far, I’ve been American centric in my focus. There are Jugs machines made specifically for soccer (global football) and cricket. And the velocity of shots or bowls have been common metrics in both games for a while now, though not as long as baseball. However, the data analytics transforming American sports has been slower to gain traction with popular international sports. Cricket didn’t start using radar guns until 1999. And soccer has been oddly resistant to deep statistical analysis.

One former head of analytics for FC Barcelona, one of the wealthiest sports franchises in the world, told 538, “The fundamental question that everyone wants to solve is, ‘How do we model the state of the game at any time, and what can we get from that about future reward?’“

In other words, despite vast resources and data, no one is quite sure why one team wins. So far, the only reliable data point is the score.

Elite athletes across sports are now facing significant improvements in training, development, and evaluation. To achieve at elite levels of athletic competition, dedicated training and practice is required. Even if you don’t want to especially talk about it. But these tools and methods are becoming so ubiquitous as to threaten to break out of modern sports and into mainstream employment.

$69,500

Starting price for Batbox, a fully immersive baseball hitting simulator made by Strikezon, a branch of Golfzon Newdin Group, the biggest indoor entertainment company in the world. While billed primarily as an arcade amusement, Batbox is also explicitly marketed for high-end training. The company told regional outlet D Magazine they were “in final discussions” with the Kansas City Royals to replace three pitching machines with Batbox simulators for the 2023 season.

VR came in handy for baseball players during the pandemic.

Who gets access and when is about to get even more important

Every job requires some type of training. Hell, most household tasks involve a good bit of it. Aspirational professions, the ones rewarded with prestige or wealth or celebrity, certainly do. While Jugs machines, radar guns, and deflection walls can be expensive, sometimes prohibitively so, such tools are within reach of many dedicated athletes in wealthy countries. The next generation simulators utilizing multi HD displays and slow motion capture cameras won’t be.

Professional teams, like the Dallas Cowboys and Tampa Bay Rays, started using VR simulators as early as 2015. In football, players and coaches have been using headsets to supplement game tape analysis. Players have said, “When you’re just watching film, you don’t get the sound, you don’t get that real-life feel of the game. With this, I can see what the structure is.” Baseball is primed to take the technology further, already allowing hitters to practice their swings with less physical stress while giving them the option of practicing against specific pitchers and pitches.

VR and super immersive simulators are still niche technologies in sports training, but they are indicators of the simulation revolution coming for larger employment. A wide variety of professions, usually pretty cool ones like pilot, race car driver, or neurosurgeon, have long relied on simulators before allowing new trainees access to expensive vehicles or vital organs. Yet, this technology is coming for more mundane industries.

In 2021, Bank of America announced a VR training program to help its associates learn skills as simple as handling service calls and opening a checking account. German rail operator DB Schenker began training forklift operators in VR in 2019 with the aim of reducing training time while giving trainees the chance to simulate their future working conditions.

Last year, Siemens partnered with VinciVR to certify 12 union workers in Massachusetts as the first VR trained offshore wind turbine technicians in the world.

There’s clearly interest in VR as a training tool and companies are exploring the space, but so far, applications have largely been limited to fields where training in real world environments is too dangerous or too cumbersome. Plus, whatever Bank of America is doing. What’s next—mandatory VR training to work at a fast casual dining chain? Too late—that first happened in 2017.

The purpose of this piece was not to say that VR is going to change everything. Maybe it will. Maybe the impact will be more muted. (My money is on that outcome.) The point isn’t even that training is important for success or that talent needs to be nurtured to achieve greatness. Or that rich kids have advantages.

Underlying this cataclysmic shift in how people are trained is the fact that those with the means, either recognized talent or financial resources, will gain access to developmental tools that will later be used as evaluation tools for a larger applicant pool.

What I mean is that the kid who grew up with a batting cage at home is a lot more likely to become a Hall of Famer. And a whole lot of industries are about to get batting cages.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal!

And thanks to Tech Brew for sponsoring.

:format(jpeg)/uploads/tedium032923.gif)

/uploads/tedium032923.gif)

/uploads/andrew_egan.jpg)