Floppy Copy Classics

A few copy-protection schemes, of varying levels of success, you’ve possibly run into over the years. Don’t lose your code wheel.

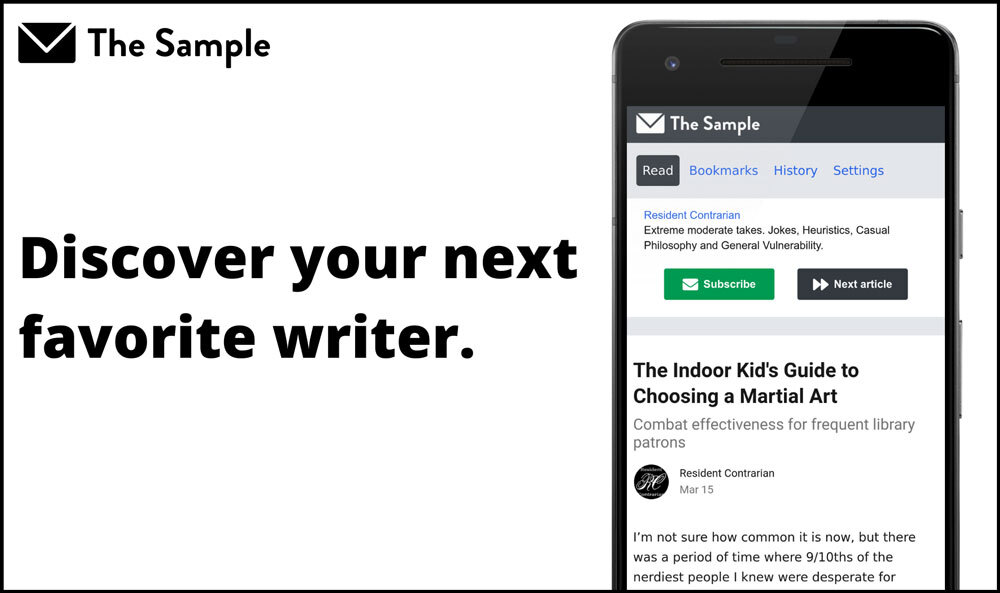

Find your next favorite newsletter with The Sample

Each morning, The Sample sends you one article from a random blog or newsletter that matches up with your interests. When you get one you like, you can subscribe to the writer with one click. Sign up over this way.

Today’s Tedium is sponsored by The Sample. (See yourself here?)

/uploads/msadv-trs80-disk.jpg)

1. Microsoft Adventure

Era: Late ’70s

Platform: TRS-80

So, this was the program that started it all, and fittingly, it was sold by Microsoft, one of the most famous companies for copy-protection schemes. As Adventure was one of the first games sold primarily on a floppy disk—rather than cassette tapes—it was a groundbreaking in more ways than one. As The Digital Antiquarian noted in 2016:

It accomplished this feat by taking advantage of the capabilities of the floppy disk, becoming in the process the first major game to be released on disk only, as opposed to the cassettes that still dominated the industry. And to keep those disks from being copied, normally a trivially easy thing to do in comparison to copying a cassette, Microsoft applied one of the earliest notable instances of physical copy protection to the disk, a development novel enough to attract considerable attention in its own right in the trade press. Byte magazine, for instance, declared the game “a gold mine for the enthusiast and a nightmare for the software pirate.”

Eventually, it was cracked by a teen from Australia named Nick Andrew, who managed to work through the sector magic that Microsoft had implemented to prevent copying. Andrew noted it was kind of like an additional game for him. “I spent around 4 days straight playing the game until I had solved it, then another 2-3 days straight working out its copy protection mechanism so that I could copy it,” he wrote.

Guess that’s one way to increase replayability.

/uploads/Lunar-Leeper.png)

2. Spiradisc

Era: Early-to-mid-’80s

Platform: Apple II

One of the more fascinating and successful attempts to prevent copying from the early era, the Spiradisc technique, developed by Mark Duchaineau during the era of the Apple II, essentially wrote the data onto the disk in a series of spiraling paths, with the goal to make it difficult for common disk copying schemes to make heads or tails of the scheme.

This copying technique is most famously mentioned in the book Hackers by Steven Levy, who noted that Duchaineau was able to convince major software publishers, like Sierra On-Line, to utilize the technique to publish their games.

Eventually, users figured it out—on his website, Andrew McFadden explains how he managed to get around the process as a teenager—but the technique held for longer than most of its kind.

Many similar attempts of differing complexity were used by a variety of companies throughout the 1980s and 1990s, but many of them were cracked fairly quickly, creating an arms race between software publishers and cracking crews of the era.

3. Lenslock

Era: Mid-’80s

Platform: ZX Spectrum, among others

One effective way to get people to stop copying? Putting a bunch of gibberish on a screen while shipping the only way to read it in the box. The LensLock was a tiny plastic lens that you put on top of your monitor in a very specific way to decipher what, exactly it said. It was a total pain to use because of its overall complexity; it required careful holding and positioning into the right spot to make the gibberish at all readable.

In a 1986 article in The Guide to Computer Living, this device was described as the worst copy protection scheme on the market—one so bad that the game Elite, which originally shipped with the device, quickly ditched it.

“Muscle cramps, eyestrain, confusion, and a severe case of rage preceded every game of Elite because the LensLock device was so cheaply made that most of the time you couldn’t tell what the second screen said even if the whole shebang was adjusted correctly,” the magazine said.

The YouTuber Modern Vintage Gamer, who has covered numerous copy protection schemes over the years and is a source I’d recommend if you’d like to further dig into this general topic, highlighted the rage the device created in a clip from last year. Fortunately there’s a decoder available today, for Windows, if you need it.

/uploads/VHS-Tapes.jpg)

4. Analog Protection System (Macrovision)

Era: Mid-’80s-Early-2000s

Platform: VHS, DVD

In the home video market, one major copying challenge that could emerge was the rise of setups where people could record films directly from other films, a process called duplication. All you needed was an additional VCR—and this likely slowed the uptake of commercial content on the VHS format (at least the non-public-domain kind).

One way that entertainment companies got around this was through an analog protection system that was undetectable in normal watching but significantly degraded the quality on copies. The best known of these systems, called Macrovision, essentially worked in the mushy middle ground between a valid signal that a TV might display and one that a VCR would pick up as legitimate. By screwing with the vertical blanking interval in the analog signal, it messed with the brightness on the final image and largely made the final result unwatchable.

While not totally unique—a 1986 Billboard article noted that the technology was similar to a technique that Sony had developed in the late ’70s—it was successful enough as to be widely used on most commercial VHS releases in the ’80s and ’90s, and even some DVD releases.

In a great irony of ironies, the company that started Macrovision later became known as Tivo, a company that found success with the exact opposite approach—making it easier to copy content for personal use—though today the firm is known as Xperi.

/uploads/Tunnels-of-Armageddon.jpg)

5. Looking up random phrases in the booklet, or using a code wheel

Era: ’80s-’90s

Platform: Various PC formats, more rarely in console games

One of the more effective copy protection techniques of its era didn’t even necessarily require cracking or additional coding, but instead required users to leverage something in the box from which they purchased the game.

MobyGames lists at least 211 separate games for different platforms used this technique, which obviously lost currency as the internet age began to pick up. Some of the best-known titles to use this tactic included Battle Chess, various King’s Quest games, and the original WarCraft.

A variant on this was the code wheel, which required users to decipher a code using an included paper device for decoding.

While obviously nowhere near enough to stop copy protection, it did help to slow it down to some degree, explaining why the technique was so widely used.

There is at least one known case of this kind of copy protection being used on a console game—StarTropics, the NES game, packaged a physical letter with the game that must be dipped into water to reveal a code that is required to complete the game. It’s widely believed that the technique was intended to discourage rentals of the game.

/uploads/DAT.jpg)

6. Serial Copy Management System

Era: Late ’80s-’90s

Platform: Digital audio tape, MiniDisc, CD-ROM

For a time, this was the music industry’s firewall for securing content, but it proved to be ineffective in the end and hugely controversial in some circles. SCMS, announced in the late ’80s, came about as an effort to appease the

Recording Industry Association of America, which had taken steps to discourage the uptake of the Digital Audio Tape in the broader market because of its ability to make perfect copies of digital recordings.

The SCMS initiative, effectively a digital hold on copying using digital devices, was combined with political pressure put on by the RIAA, which managed to get the security technique implemented into emerging mediums like DAT, the CD-R, and the MiniDisc thanks to a mandate in the Audio Home Recording Act of 1992. The effort to force SCMS likely sank the potential of the DAT format in the U.S.

The problem, as you might have noticed, is that the SCMS did not account for the rise of the MP3 or other computer-based audio, which meant that the whole idea was completely undermined the the end of the decade.

(If you want to learn more about DAT, I recommend this Twitter thread, but be sure to look quickly before Elon Musk takes it down!)

/uploads/GD-ROM-example.jpg)

7. Sega GD-ROM

Era: Late-’90s, early 2000s

Platform: Sega Dreamcast

When is a CD-ROM not quite a CD-ROM? How about DVDs—when is a DVD not quite a DVD? The answer to this question, of course, is when they’re being modified to only work with specific video game consoles.

This was a technique that Sega and Nintendo each tried, to different degrees of success, around the turn of the 21st century.

Sega’s attempt, called the GD-ROM, was essentially a more-tightly-packed CD-ROM based format that could hold a gigabyte of data, and the copy protection used relied on a mixture of the format’s proprietary nature and a mechanism that required part of the boot sequence to run from the disc itself. However, one of the format’s more obscure features, a multimedia CD-ROM format called MIL-CD, eventually opened the door to simply burning the disc and downscaling samples to fit on the smaller size—a problem that was worsened when a SDK for the Dreamcast was stolen, revealing a security-though-obscurity approach that was then broken, hastening the Dreamcast’s demise.

/uploads/GameCube.jpg)

8. GameCube Game Disc

Era: Early 2000s

Platform: Nintendo GameCube

Meanwhile, the Nintendo GameCube had slightly more luck with its proprietary optical format.

The platform, which relied on miniaturized variants of a traditional DVD optical disc, largely was able to avoid the fate of the GD-ROM format because of multiple modifications to the format, including the use of a “burst cutting area” that was used as a unique identifier for the discs. Datel, the makers of the Action Replay, found a way around this issue, but for the most part, users who wanted to use homebrew discs instead found themselves having to rely on mod chips or, later, SD cards to boot their games.

/uploads/HDCP.jpg)

9. Digital Transmission Content Protection (DTCP)/High-bandwidth Digital Content Protection (HDCP)

Era: 2000s-Present

Platform: Television, DVDs, displays

These similar but separate techniques, used by television sets in particular, essentially are used to ensure the encryption of data as it travels along a specific path, so it can’t get intercepted in the middle.

In some rare cases, you may see errors when playing video content through an HDMI cable, for example, because of an HDCP error—essentially a false positive that can occur when streaming content.

Both technologies are widely used, with HDCP likely more common for people to run into in everyday use. HDCP’s security functionality has somewhat declined in value since its launch, in part because of the fact that its master key leaked more than a decade ago, limiting a key part of its primary capabilities.

Also, one has to wonder if the techniques are so common today as to render their encryption value useless? After all, when was the last time you had to break into the middle of an HDMI stream?

10. Cactus Data Shield/Extended Copy Protection

Era: 2000s

Platform: Audio CDs

One of many attempts to put the genie back in the digital bottle by the music industry, Cactus Data Shield, developed by the Israeli company Midbar at the behest of EMI and BMG, is designed to discourage the copying of files onto a disc through a mixture of audio corruption and a complex structure that makes the disc complex to copy. (For one thing it has a data session that includes low-quality audio, rather than the high-quality stuff CD players get.)

This format proved hugely controversial when it was shown that the discs did not play in a number of normal players—something a bunch of German consumers learned the hard way. The copy protection efforts were eventually discarded by EMI entirely in the mid-2000s.

A similar approach is Sony’s Extended Copy Protection, which you might remember well if you grew up in the mid-2000s because it was at the source of a major security scandal, as the copy protection scheme installed a rootkit on users’ computers. The response to that was enough that it stopped the copy-protection efforts by the music industry dead in their tracks for a few years.

Check out the clip from VWestlife above for more background on this phenomenon.

These days, copy protection is very much still around, despite controversy about it, and has become something of a moot point in many cases as the value of content has declined as a whole.

One of the most effective forms of copy protection, in the end, has proven to be the idea of activation—that is, phoning home to a server when you use a program—hugely popular applications such as Adobe’s Creative Cloud do it, as do many modern PC games. (Much to the chagrin of Steam Deck owners.) Because of activation, you have to constantly pay for content to continue to have access to it, and while it hasn’t necessarily killed piracy, it has done a lot to dampen some of its effects.

But even there, the technique has found its limits. Around the time of the Xbox One’s release, Microsoft had attempted to change its model to favor always-on internet access and digital downloads, while limiting the resale of physical games. But fan complaints about this change led Microsoft to change its approach, and to this day you can buy physical games if you want them.

There are ideological reasons to disagree with copy protection, and none of what I said here discourages you from disagreeing with it. I recommend checking out the work of Cory Doctorow if you need a starting point. That said, the best copy protection, the one you’re likely to live with, will always be the least intrusive—if it makes your life easier and gives you additional choice, you’ll live with it.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal!

Are you a Mastodon user? Be sure to give Ernie a follow!

And thanks to The Sample for giving us a push this time. Be sure to subscribe to get an AI-driven newsletter in your inbox.

:format(jpeg)/uploads/tedium111622.gif)

/uploads/tedium111622.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)