You Spin Me Right Round, Baby

Before hard drives became the main way for us to back up our stuff, they were a key evolution for the business world. They were also huge and costly.

Today’s Tedium is sponsored by the cloud security service Nightfall. More from them in a second.

169

The number of patents Austrian inventor Gustav Tauschek sold to IBM in his lifetime. One of those inventions, an early form of disk storage called drum memory, involved using a spinning metal drum to access data on a magnetic cylinder. The storage technology, which directly inspired the later invention of the hard drive, was used by many early UNIX machines throughout the 1970s. Like later disk drives, drum memory relied on mechanical heads to read and write material onto the disk; unlike later disk drives, the heads were stationary, and did not access data at random but instead grabbed the data as the drum spun around. (Tauschek, by the way, was involved in some of the earliest attempts at optical character recognition with his reading machine, which dated to 1929.)

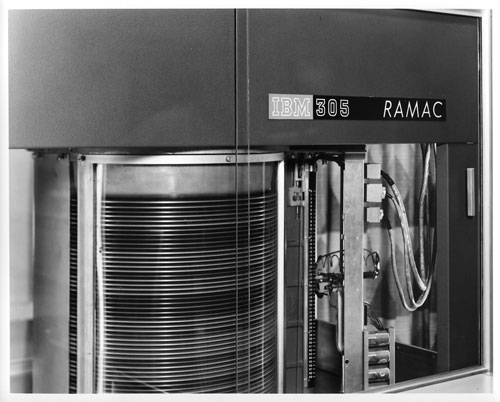

Those platters are friggin’ huge, aren’t they? (California Digital Library)

The philosophy behind the first hard disk, which was made by IBM, of course

If you were to explain to the public what a hard drive was with no prior frame of reference, where would you start? How would you highlight the benefits to the world?

That’s an odd, somewhat theoretical problem today, but in 1956, it was legitimately a challenging problem that IBM had to solve. At the time, “business machines” often meant storing information on punch cards and and typewritten pages, which meant that the file cabinet business was doing quite well back in the day.

The difference between a punch card and a hard drive is quite similar to the difference between the Dewey Decimal System and microfilm—one organizes content that’s completely physical while the other shrinks the scale enough that it allows for some degree of rethinking how we access the content. With a hard disk, it doesn’t have to necessarily be in order anymore. It adds a layer of separation between you and the information being displayed.

In many ways, the IBM 305 RAMAC (Random Access Method of Accounting and Control), which was initially built for the needs of accountants, represented this sort of abstraction. Designed at the behest of the U.S. Air Force, it was meant to provide faster, more efficient storage of information than magnetic drums.

“This has been a day of solid achievement,” the first message ever stored on a hard drive stated, according to a 2002 ComputerWorld article.

Upon its 1956 release, the mainframe machine was the first to allow for any form of hard disk storage, and while the 350 Disk Storage Unit was stored in a centralized place, it was not a tiny piece of technology, requiring very large spinning platters of around 24 inches in diameter—or twice the diameter of a full-size vinyl record. Per the company, a single platter could hold up to 5 million individual characters on a single disk—or, in other words, five megabytes.

Of course, IBM had to explain why an accounting team would actually want this, and they did so by comparing it to the paper-based ledger system originally used for bookkeeping, which was often quite cumbersome, could often lead to human errors. In a 1958 reference manual for the 305 RAMAC, the company described the benefits of an alternative approach called in-line processing. Explaining the approach using an example of a manufacturing company purchasing raw material, the company explained the benefits as such:

In the example just mentioned, the clerk changed the balances in the cash account and the raw material account. The next transaction could reflect the fact that some of the raw material had entered the manufacturing process, in which case the clerk would subtract this amount from the raw material account and add it to the material-in-process account.

However, it is more probable that the next transaction would affect entirely different accounts. Perhaps some of the finished products were sent to the wholesaler. This transaction would affect the inventory and accounts receivable balances.

Because the clerk has direct access to all of these accounts, he can complete the posting of each transaction before beginning the posting of the next. This accounting method is called in-line processing.

In-line processing has previously not been practical in automatic accounting systems because of the difficulty of reaching and changing single records in large files. However, with the introduction of the IBM 305 RAMAC which is built around a random-access disk storage unit that permits the storage of 5,000,000 characters of business facts (the equivalent of 62,500 80-column IBM cards), in-line processing is now a practical reality.

The platform, which relied on punch cards for both input and output, nonetheless allowed for a much more sophisticated form of storage than was previously possible.

A short promotional film about the RAMAC (which amusingly features the mainframe machine sitting next to standing water at one point) spoke to the same issues—featuring at one point an endless sea of filing cabinets—and described the development process, which revealed that research and development teams were directly inspired by both the properties of magnetic tape storage and the random scanning allowed by record players.

“But scanning tape to find a single fact takes time, unlike finding a place on a record,” the film explained.

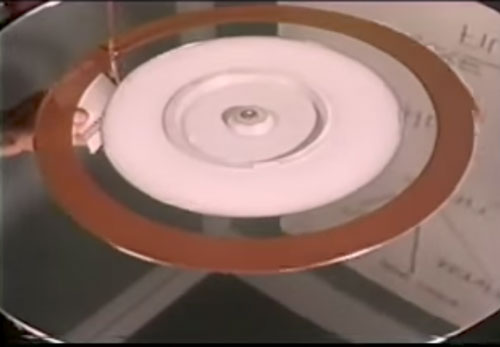

A RAMAC disc platter gets coated. (YouTube screenshot)

So IBM, essentially, combined the two concepts—using magnetic data storage and making it possible to access the data randomly, like a vinyl record. Pretty cool, huh?

While the device might have been intended for accountants and other business-specific uses, it quickly found other contexts. For example, the U.S. Coast Guard used RAMAC to help with search and rescue missions, and the 1960 Winter Olympics relied on a RAMAC 305 to help score and immediately tabulate the results of a contest—something that had previously taken hours to do.

Ford even used the mainframe’s storage power to do some primitive market research on a small town called Flora, Illinois. In 1960, the company fed detailed survey data on the town’s roughly 5,000 people into a RAMAC, along with (of course, their opinions on the company’s 1961 line of vehicles.

“Every available statistic on Flora and its citizens will be recorded in the RAMAC. To the best of my knowledge, never before has the introduction of a new car been studied with such searching thoroughness,” said George H. Brown, the manager, of Ford’s market research division, in a 1960 Arizona Republic article.

And that’s what they did with a five-megabyte hard disk in 1960.

Sponsored By Nightfall

Which Go regex engine is fastest?

At Nightfall we spend our days developing the best way to identify sensitive data in a wide variety of contexts. It is not just a simple regular expression, but it often starts out as one! Learn more about the process we use to build and optimize our platform with a deep dive comparison of regular expression engines in our preferred language, Go, here. Let Nightfall focus on keeping your data secure at scale so you can focus on building your core applications.

No, that’s not a motor: That’s a key component of a IBM 3380 hard disk. (Wikimedia Commons)

Five interesting facts about early hard disk drives

- The drives were insanely expensive. IBM’s mainframe business, in a lot of ways, was not designed for mere mortals, and likewise, the firm charged top dollar for RAMAC and later innovations. Upon its launch, it charged $3,200 per month just for companies to use those massive five-megabyte hard drives. And prices stayed very high for years after.

- Early platters were designed to be removable. Vintage hard disks, in many ways, don’t look a lot like the drives you’re used to these days. Instead, the devices were notable for allowing the use of removable disk packs, a strategy that was designed as something of a cost-saving measure during the 1960s, when hard disks were hugely expensive. The problem is that swapping disks on platforms like the IBM 1311 was difficult, because of the need to align the disk head.

- Early instability in hard disks kept alternatives around. The punch cards and tape drives were not just there for show. If there were issues with the disks, which required great care to even swap out, a whole lot of data could be lost in an instant. (Simply, there were a lot of moving parts and a lot of room for things to go wrong.) This helped set the stage for backup needs in the enterprise—something that magnetic tape is still used for today in some instances.

- An key innovation in hard drives was nicknamed after a gun. The “Winchester” drive, which IBM came up with as an internal name for its IBM 3340 drive, partly relied on a “fixed disk” system to hold the platters in place—a design decision that ultimately sped up the drives by allowing the drive heads to get extremely close to the platters, and redefined the industry. The drive, which was nicknamed for the Winchester .30-30 rifle cartridge, was to hold 30 megabytes of fixed data and 30 megabytes of replaceable data. (It actually used slightly larger disks in practice.) The Winchester drive is the basis for modern drive designs today.

- Larger capacity meant bigger sizes. Some early hard disks made by IBM, like the 1311, were about the size of a top-loading washing machine, and when the company hit the gigabyte barrier in 1980, they did so with a the 3380, a device roughly the size of a large refrigerator, and one that cost around $40,000. Just 20 years later, the company had released a device with quarter-sized disk platters that held the same amount of data for less than $500.

“Most recently 5¼-inch fixed-disk drives have become available. Seagate technology and Shugart were among the the first to ship these smallest Winchesters, which average about five to six megabytes in capacity. Because of its all size—the same size as a mini-floppy disk drive, the 5¼-inch fixed disk seems about to be widely incorporated into integrated desktop systems.”

— InfoWorld scribe Thom Hogan, discussing some of the earliest hard disk drives that were compatible with microcomputers in a May 25, 1981 article. The disks were incredibly expensive for their time, but proved hugely influential. Seagate’s work on its ST-506 drive became one of the PC industry’s earliest standards, though its impact would not be felt for a few years, as PC-based hard drives did not become common until the latter half of the ‘80s, in part because of the devices’ price. (IBM did not lead this part of the digital revolution, really; firms like Seagate and Western Digital hopped out front, and IBM eventually sold off its hard drive business.) Beyond being one of the earliest references to the ST-506, the article described at length large disk drives that often provided larger capacities in exchange for larger sizes. Drives as large as 14 inches wide were still relatively common during this time.

Over the years, the hard drive has seen a whole bunch of evolution, in part because of ever-shrinking technology and constant improvements. Fridge-sized machines gave way to hard drives the size of your finger; complex spinning disks kept getting faster and more sophisticated; and we learned how to say the word “defrag.”

Clearly, the hard drive is not the newest kid on the block anymore—in terms of its spot on the Hype Cycle, it’s long been on the “Plateau of Productivity,” with its use cases becoming less and less novel. But the drives, of course, are still getting smaller, more nimble, and cheaper.

In an era when flash memory and solid state drives are the hippest, newest technologies on the block, the hard drive feels a little old hat, even as it constantly becomes cheaper—you can buy a 1-terabyte hard drive, infinitely more than the enterprise could have imagined 60 years ago, for less than fifty bucks. It’s closer to the tape drive than it is solid state in some ways on the age front. But in some ways, it’s come full circle.

The hard disk started as an abstraction—a way of reconsidering the conceptual limits of what came before—and in the age of cloud computing, it’s the key element of another abstraction, one built around storage that’s far from home, accessible over wires, but ultimately comes from a hard drive in many cases.

Most technologies are lucky to be at the center of a single major abstraction of innovation. The hard drive is at the center of two.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal!

And thanks again to Nightfall for sponsoring.

:format(jpeg)/2017/05/tedium053017.gif)

/2017/05/tedium053017.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)