Honey, I Shrunk The Page

Microfiche (or microfilm, depending on how you roll) is a library mainstay, but its history is wild, according to this note I got from a carrier pigeon.

"To John Benjamin Dancer, a man of strong character and immense energy; alert and practical, a skilled craftsman and manipulator; sympathetic, ever ready to help the youthful searcher, inventor of microphotography, the National Microfilm Association is proud to present this posthumous Medal of Meritorious Service to the microfilm industry."

— The text on the Dancer Pioneer Medal, an award handed to E.C. Wilkie, the great-granddaughter of John Benjamin Dancer, in 1960. What did Dancer do that was worthy of such great praise? Easy: He invented microfilm, the process of shrinking a full-size photograph into a very small size. (By the way, just to clarify the terms, "microfilm" is usually distributed in roll form, like you would pull out of a 35mm camera, while "microfiche" is flat.) Dancer, whose father owned an optical goods firm, combined his family's chosen trade with the then-new daguerreotype process of photography, and started tinkering. Soon, he was able to shrink large objects by a ratio of 160 to 1. He also created an early example of photomicrography, the process of expanding an image of something small to a large size, when he created a six-inch daguerreotype of a flea. It took generations for Dancer to get his due for his groundbreaking work, but the award handed to his great-granddaughter played an important role in making up for that.

(via Luminous-Lint)

Microfilm's first innovation: Improving carrier pigeon efficiency

In 1859, two decades after Dancer created the microfilming process, Frenchman René Dagron improved upon, standardized and patented the concept. But like graphene in the modern age, the technology was a major innovation in need of a use case.

Dagron found one during the Franco-Prussian War, a period that necessitated the transfer of information from outside of Paris back in. Being that electronic telecommunications were still in their infancy at this point, carrier pigeons were in wide use, with such pigeons being dropped out of hot air balloons outside of the city, with the assumption that they would eventually fly back in.

Of course, there's only so much information that you can put on a sheet of paper that's light enough for a carrier pigeon to carry. This of course, was when the candle lit up over Dagron's head (because there weren't light bulbs back then).

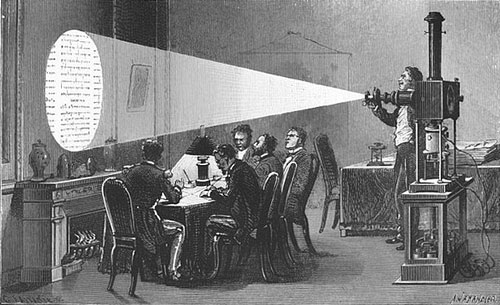

Dagron recommended to French Postmaster General Germaine Rampont-Lechin that they use his technique to create tiny microfilmed photographs of documents that needed to be sent into Paris, then put them inside tiny tubes attached to the carrier pigeon's wing. Since the images were visible with the use of a magic lantern—an early form of film projector—this allowed for the discrete distribution of messages to and from the battlefield.

The strategy nearly failed, however, when Dagron and his team were attempting to leave Paris by balloon. Their balloons were shot out of the sky, and his team was almost captured by Prussian forces, with their equipment lost in the shuffle. Eventually, though, they made it to the city of Tours, where a chemist, Charles Barreswil, had already attempted to send tiny photographs with the carrier pigeons. After a few technology-related hiccups, Dagron was able to make tiny prints that were so small (11mm by 6mm) that a single carrier pigeon could carry up to 20 sheets in his tiny tube. That was a massive upgrade from Barreswil's technique, which could only shrink images to 37mm by 23mm photographs.

The technique was successful—more than 150,000 tiny sheets of microfilm were brought into Paris using this technique—but Prussians realized what was happening and tried to take the birds down. The Times of London, in an 1870 report, explained exactly how:

It is said that the pigeon post is gone off, with sheets of photographed messages reduced to an invisible size, and which in Paris are to be magnified, written out, and transmitted to their addresses. They are limited to private affairs, politics and news of military operations being strictly excluded. But the Prussians, it is said, with their usual diabolical cunning and ingenuity, have set hawks and falcons flying round Paris to strike down the feathered messengers that bear under their wings healing for anxious souls.

Carrier pigeons did not have an easy job, apparently.

1906

The year that groundbreaking information scientist Paul Otlet first argued, with the help of his colleague Robert Goldschmidt, that microfiche should be used to archive old books and other documents, due to the fact it takes up a lot less space than actual books do. This pitch, which Otlet and Goldschmidt made in a paper titled Sur Une Forme Nouvelle Du Livre: Le Livre Microphotographique (the full document is at the link, but it's in French), did not immediately set the microfiche world ablaze, even after the duo showed off a Steve Jobs-style demo of the technique at the American Library Institute's annual meeting in 1913. But in the 1930s, publications such as The New York Times and libraries such as that at Harvard University began using the format as a way to preserve old newspapers.

Microfiche helps ensure that classic comic books don't lose their superpowers

These days, the internet has quickly usurped microfilm and microfiche as the researcher's tool of choice. For good reason! The internet puts way more stuff at your fingertips.

But there are some cases where microfiche arguably does a better job, and one of those cases involves classic comic books, which are well-represented on microfiche at some major research libraries. There are three reasons for this:

Low-quality source material. As you may or may not know, comic books were not originally published using the highest quality of paper or ink, and as a result, they have not aged well. Microfiche that's decades old, on the other hand, holds up pretty darn well.

High cost of original copies. Old comic books are incredibly valuable, and as a result are out of financial reach for most people. And that includes libraries as well. The library at my alma mater, Michigan State University, has a comic book collection with more than 80,000 entries. But it is no longer purchasing original copies due to "the fragility and great expense of most of these items." Instead, it's buying microfilm, which can be recreated at will.

General snobbishness. The New York Public Library has a wide collection of comic books on microfilm, but the reason much of that collection has been archived in that form wasn't out of a desire to protect it, but because comics were once deemed unfit for a library. "Unfortunately, as with other genres of popular literature such as science fiction, comic books were often considered unworthy of addition to research library collections," the NYPL website states. "The original NYPL Research Libraries policy was to collect representative samples of comic books and microfilm them. Emphasis was not placed on keeping original material."

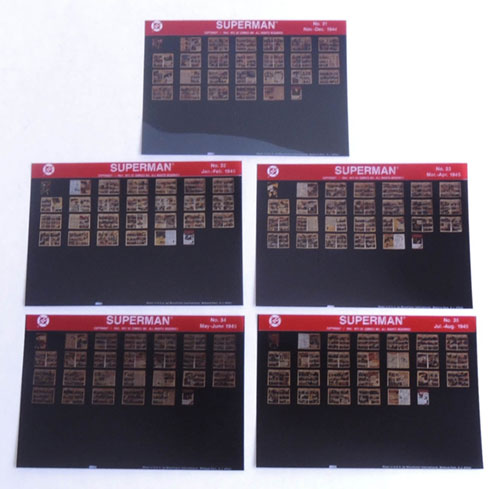

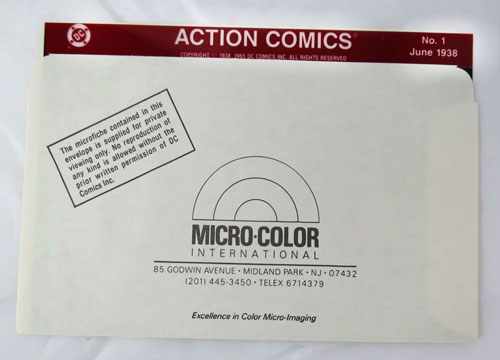

And it isn't just libraries getting into this game. In the '90s, a company called MicroColour started printing old, full-color copies of vintage comic books on microfiche, while also selling a compact microfiche reader. The idea was to make decades-old comic books available to the average consumer at a tiny fraction of the cost of the actual book.

While classics like Superman and Batman are no longer for sale on the site (although some can be found on eBay), the company still does sell classics like Archie Comics and Fiction House's Planet Comics anthology series.

(Why microfiche in the '90s? According to a 1997 article about the phenomenon, MicroColour founder Ara Hourdajian said the comic book makers were opposed to making digital versions of their pages at the time.)

Considering that comic books gave microfiche a little extra life, it makes sense, then, that there's a comic book about Eugene B. Power. Power is the guy who founded University Microfilms International (UMI), the company that brought microfiche to libraries around the country, in 1938. (Power's company is still going strong, by the way; you may not know UMI, but if you've stepped in a library sometime in the last decade, you've most assuredly heard of ProQuest, which makes some of the most widely used library research technologies.)

$4,150

The current price on Amazon for the USB 3.0-enabled Micro-Image Capture 8, which can scan in microfilm pages and digitize them with ease. The device is pretty much the top of the line in terms of microfiche readers these days, though not to be outdone, ST Imaging's ST ViewScan III is capable of sending scanned microfilm images to a Dropbox or Google Drive folder, as well as doing color microfilm scans. I have no clue how much the ViewScan costs, though. As I learned recently when researching printers for shirt tags, the best way to tell when something is expensive is when you're required to email them to get them to tell you the price.

Microfiche isn't perfect. Compared to the scrolling you do on your phone, it has a clunky interface that requires a lot of scrolling before you can reach the exact page you're looking for.

To get an idea of these interface weaknesses, check out this clip of Chevy Chase using a microfiche projector in the 1985 film Fletch.

There are other problems, too. It doesn't capture the level of detail of a high resolution photo you might see online. It does text justice, but you can't say the same for photographs, which are often grayscale at best.

And the projectors themselves that you might remember from your library days, which generally predicted the basic shape and format of desktop computers, are hard to find, let alone purchase. You can generally find them new at MicroFilmWorld, but the prices are a pretty great reminder that when a product has a very specialized use case, you'll likely be paying a specialized price. (You'll have better luck on eBay.)

But here's the secret with microfilm that will ensure its existence for generations to come; it's designed to last for hundreds of years, far longer than any hard drive or CD-ROM ever will.

In a couple hundred years, when people are trying to write the history books about our culture, they're probably going to run into a lot of 404 errors—as I did when I was trying to find the link in the previous paragraph.

But you know what they'll be able to read crystal-clear, without any issues? Microfilm and microfiche—just as Paul Otlet, John Benjamin Dancer, René Dagron, and a bunch of other film experimenters realized back in the day.

(Of course, our future historians probably won't have the right equipment, anyway.)

:format(jpeg)/2018/01/k1oi9ppnlfbdq57kfmk5.gif)

/2018/01/k1oi9ppnlfbdq57kfmk5.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)