Wiki-Fail

Looking with fresh eyes at the Wikitorial, the Los Angeles Times’ extremely misguided attempt to bring the wiki concept to the newspaper editorial page.

By the way, our promo with Letterjoy is still going on. More details here, or later in the piece. Thanks!

/uploads/0502_times.jpg)

Why the editorial page may have been the worst possible place to test a wiki-related idea

The thing to understand about any big-city editorial page is that people have strong opinions about editorial pages.

Unfairly or not, nearly every major hire that The New York Times has made for its editorial page in recent years, including Sarah Jeong, Bari Weiss, and Bret Stephens, has raised the ire of somebody.

James Bennet, the NYT’s editorial page editor, has received much criticism for his running of that page, though much of that criticism has died down in recent months, even if it occasionally resurfaces.

Fact is, no matter your opinion of any of these people, they by default have targets on their back because they’re on a particularly influential page, one that helps set the national political discussion.

Of course, they’re not alone in the arms race that is the editorial page. Political cartoonists, even well-regarded ones like Rob Rogers (formerly of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette), have run into an array of issues over the years. And letters to the editor can feel like a cesspool given the right environment and wrong story.

Despite its formal tone, editorial pages are places where ideology turns into a street fight. Much like the talk pages of prominent Wikipedia articles, as it turns out!

I have a little bit of experience with this, thanks to a job I had early in my career. In 2005, I was relatively fresh to journalism, and I would follow technology-related experiments closely—I even worked at one, a small-town South Carolina paper called Bluffton Today that, at its outset, gave everyone in the area their own free blog, if they so chose to post on one. And if you didn’t own a computer, we literally printed the blog posts placed on the website in the back of the paper, which we gave away for free to everyone in the community. It was a crazy little experiment—the first of many that I got to take part in as a journalist.

One thing that was fascinating about this paper was that it seemed, at times, to help accentuate the people with the strongest opinions in the local community. Their opinions somehow became louder thanks to the blog-style format.

I thought that the paper was amazing, and I still do, but given the roughly 14 years since I worked in that newsroom, I feel like the reaction that we sometimes saw from our more passionate readers was at times a microcosm of the arms race we see with modern political opinion online.

Another example of such opinion-minded experimentation was happening on the other coast, in the offices of the Los Angeles Times, in mid-2005.

Going back to the NYT and Bennet, say what you will about his work, but he’s already stayed in his role far longer than Michael Kinsley stayed in an equivalent role at the L.A. Times in 2004 and 2005.

Even though Bennet has stayed on for a few years at this point, their reigns as op-ed page leaders are pretty easy to compare: Bennet, whose brother literally just announced his presidential candidacy, came to the role after serving as editor-in-chief of The Atlantic during a time when the magazine significantly expanded its digital presence.

/uploads/0502_kinsley.jpg)

Like Bennet, Kinsley was a veteran of the magazine and digital publishing worlds, having edited Harper’s and The New Republic, and serving as Slate’s founding editor. Kinsley is also, of course, known for his time as one of the CNN show Crossfire’s flamethrowers, generally sharing the liberal point of view.

Kinsley left Slate and Crossfire in 2002, after announcing he had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, but returned to journalism in 2004 with the L.A. Times role.

By taking the helm of an editorial page at an iconic big-city media outlet, Kinsley found himself in a tough environment not unlike the one that Bennet has dealt with at the New York Times. Kinsley’s status as a liberal commentator on television came to haunt him as figures like Bill O’Reilly publicly criticized him. And he at times found himself caught in the middle of controversies similar to those Bennet has faced.

An example of this came in early 2005, when USC professor Susan Estrich, a feminist commentator, toughened up a campaign to get the newspaper to include more women on its editorial pages. Estrich had a fair point, but some of her emails to Kinsley, which leaked online because she also forwarded them to other journalists, jabbed pretty hard. From a 2005 L.A. Times article:

In a series of e-mails to Kinsley—some of them copied to journalists, who quickly posted them on the Internet—Estrich questioned Kinsley’s mental powers and judgment, predicting his days at the newspaper were “numbered.”

Referring to Kinsley’s Parkinson’s disease, she wrote that “people are beginning to think that your illness may have affected your brain, your judgment and your ability to do this job.”

As a result, Estrich’s already icy relationship with the newspaper’s op-ed operation has gone into a deep freeze. Kinsley has accused Estrich of “blackmail” and called her comments about his health “disgusting.”

So not exactly an easy job, but Kinsley likely knew that going in.

But one other place where Bennet and Kinsley have a lot in common is a willingness to experiment online with what an editorial page can be. Last year, Bennet’s paper put out an open editorial call for “visual op-eds,” and cited examples of tap-based essays and video games the newspaper had produced. And recently, the newspaper launched a special feature called “The Privacy Project,” a large structured special project around digital privacy. The NYT is one of the biggest papers in the world; it can get away with stuff like this.

In 2005, Kinsley was equally willing to take risks, and that willingness came most prominently in the form of the Wikitorial, which may perhaps be the most ambitious, if misguided, efforts to introduce user-generated content to journalism in history.

It lasted 48 hours.

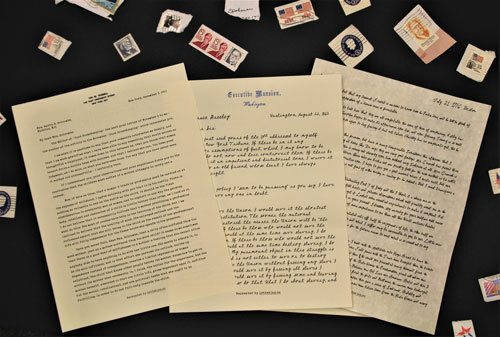

Get history (snail) mailed to your door

Have you ever wanted to receive a letter in the mail from George S. Patton, Florence Nightingale, or Frederick Douglass? Letterjoy will mail you one curated letter from history every week. We recreate the experience of originally receiving the letter, from the letterhead to the signature, and mail it to your door on fine stationery with a real stamp.

Every month focuses on a new topic, from Civil War Innovation to Presidents & The Press, and each letter approaches that topic from a new angle. Alongside each letter is a “postscript” filled with historical information from our researchers, to put the letter in its proper historical context.

Our memberships make great Mother’s Day and Father’s Day gifts, but they also make great gifts to yourself and your family. To learn more about the Letterjoy experience, visit Letterjoy.co.

(By the way: This month’s $10-and-up Tedium patrons will receive a one month personal trial of Letterjoy as a benefit of their patronage. Want a trial of your own? Sign up on the Tedium Patreon page by May 6—and make sure your address is filled out!)

“Simple courtesy demands that if you add content here, you add it from that perspective. Please have courtesy for others and understand that even if people do not agree with you, they have a right to a voice.”

— A line at the top of the LATWiki’s entry for “Counterpoint to War and Consequences,” a portion of a Wikitorial the newspaper published in June of 2005. The endeavor, published using the same kind of backend software that Wikipedia uses, was intended to allow users to add commentary and counterpoints to the essay, with the idea that an alternative point of view could be forged together by the crowd, much like a Wikipedia article. (The original essay, in non-Wikitorial form, is still online today. The Wikitorial didn’t last so long.)

/uploads/0502_wikitorial.jpg)

The experimentation that led to the Wikitorial, and the vandalism that immediately killed it

“It may be a complete mess but it’s going to be interesting to try. Wikitorials may be one of those things that within six months will be standard. It’s the ultimate in reader participation.”

In the middle of 2005, Michael Kinsley wanted to reboot what an editorial page could be. Given the job of supervising the opinion and editorial pages, he started taking bold steps to reinvent things, including introducing more reader-generated content and pushing away from the traditional form of the editorial page.

Kinsley was right—it was messy, and not just because the newspaper was doing something so experimental. He did it while completely reshuffling the staffing of the section, transferring some staff, laying off others, and offloading some of the paper’s editorials to freelancers. Kinsley wanted nothing less than to rethink what a modern newspaper opinion section could be.

And nowhere was this as risky, or as buzzwordy, as the Wikitorial.

At the time the Wikitorial surfaced, user-generated content was a major fad in journalism, along the lines of the much-ballyhooed “pivot to video” from a few years back, or the then-contemporary “hyperlocal news.”

During this era, social networks like MySpace and Facebook were still in their infancy, and the blogosphere was perhaps at its peak. In a couple of years, social networks would eat up most of the innovation conversation, but in 2005, other parts of internet culture were getting more attention—like the wiki.

The wiki was truly worth writing home about, and then letting someone else edit after the fact. I, of course, covered last year how Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger came up with their idea to organize information in a wiki format from the roots of an R-rated network of webrings called Bomis. By 2005, though, this history was already forgotten: The wiki was a big thing, with Wikipedia clearly navigating its path to success.

There were plenty of critics of the concept, such as Andrew Orlowski of The Register, and they picked up after it surfaced that journalist John Seigenthaler had a line on his Wikipedia entry that incorrectly implied he was involved in the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy.

In late 2005, Orlowski reported that Wales had been killed in a story he reported straight—because that’s what his Wikipedia page said at the time, and clearly it must be accurate!

And Orlowski and similar critics were given plenty of fodder when Michael Kinsley’s editorial department landed on the Wikitorial, an attempt at allowing user-generated commentary in a similar way.

/uploads/0502_wales.jpg)

The editorial department had an essay on the Iraq war, as well as a plan for making it work—and support from Wales, who offered volunteer help to the endeavor and came up with the idea of “forking” the editorial to allow for alternate responses.

“I’m proposing this page as an alternative to what is otherwise inevitable, which is extensive editing of the original to make it neutral … which would be fine for Wikipedia, but would not be an editorial,” Wales explained of his plan.

But as it does on Wikipedia itself sometimes, the internet’s sense of anarchy soon showed itself.

Anyone who has been on the internet for longer than 30 minutes knew what would eventually happen to the wikified “War and Consequences” editorial: Digital vandals, seeing an opportunity for dissonance, would see this pure thing that was getting a lot of attention, and that they could add to, and they made some unwelcome changes.

At first, it was profanity. But soon, as it got attention, it got worse.

Michael Newman, the L.A. Times’ deputy editorial page editor and the journalist who came up with the Wikitorial idea, literally found himself faced with a choice: Continue to remove the stream of profanities, or get some much-needed sleep.

“We were taking stuff down as soon as it went up and staving them off,” Newman told The New York Times. “Finally, we had to go to bed.”

This turned out to be a mistake. Someone was repeatedly replacing the editorial with a famous “shock photo,” despite the efforts of the newspaper to revert it to the original piece. (If you were into internet culture in 2005, you probably know which shock photo it was.) People, of course, noticed.

“Someone called the newsroom a little bit before 4 a.m. and said there’s something bad on your Web site, and so we just took the whole site down,” Newman continued.

At 4:30 a.m. in the morning on a Sunday—at a time when, in a prior era, a paperboy might just be waking up to start his route—the website’s general manager, Rob Barrett, made the call to take down the interactive feature completely. By 5 a.m., it was offline entirely.

Newman pinned the blame on one specific site: Slashdot. “Slashdot has a tech-savvy audience that, to be kind, is mischievous and to be not so kind, is malicious.”

(Slashdot’s Rob Malda got a laugh out of it, writing: “Apparently Michael Newman thinks that all half a million daily Slashdot readers are malicious, although I personally would guess more like a 60:40 split myself grin.”)

Whoever was to blame, the endeavor proved a major embarrassment for the L.A. Times, which initially promised a second stab at the Wikitorial, but it never came to be. It’s clear what the solution was here: Allow moderators to approve changes, rather than simply letting the edits go directly onto the site. But apparently that small concession wasn’t enough to save the experiment.

Three months after the Wikitorial came and went, Michael Kinsley was out, with his attempts to modernize the editorial section having been pushed off to the side. It wasn’t a departure under perfect circumstances, with Kinsley taking a dig at then-publisher Jeffrey M. Johnson on the way out.

“For whatever reason,” Kinsley wrote at the time, “Jeff isn’t merely uninterested in any future contribution I might make, but actively wants me gone.”

Kinsley, who still occasionally writes for the newspaper, pushed forth a number of radical experiments beyond the Wikitorial, but for all his attempts to breathe new life into the opinion pages, his efforts may have been ahead of their time—or, perhaps, a harbinger of what the internet was about to do to the public discourse.

It’s weird how a solid 14 years of perspective has changed my views on this kind of user-generated content.

In 2005, at the ripe age of 24, I thought the Wikitorial idea was awesome, because it was so willfully risky! If it had worked, it would have become a new way for the public to engage with the news. (But only if!)

Most of my journalistic peers, if I remember right, didn’t agree. But I had a reason for my unique viewpoint: At the time that it was published, I was days away from starting at a newspaper that made user-generated content a major component of its whole model. The Wikitorial was in my wheelhouse.

/uploads/0502_bluffton.jpg)

Bluffton Today, which adeptly combined the trends of hyperlocal news and user generated content, quite fortunately never had a moment where everything completely went off the rails like the Wikitorial did. But there were days where the website got so toxic that we had to take a step back and let things cool off a while—something that we can’t really do with our modern social networks.

I lasted in my role there about as long as Michael Kinsley lasted in his, a little over 14 months. My reasons for leaving were different—I was not forced out, but I was restless and missed living in a city. (I have a number of friends from that time that worked at this amazing little paper.) The paper, sadly, suffered during the recession, and while it exists today, some of its more experimental features—such as giving the paper away for free to everyone in the community—didn’t stick around.

Steve Yelvington, the media exec and journalistic tinkerer who helped formulate the idea, noted on its tenth anniversary that the grand experiment, which received lots of attention upon its launch, lost ground to social media.

“Facebook has conquered the community conversation,” he wrote. (I imagine Nextdoor is probably also doing some direct damage at this point as well.)

Given some time and distance away from this period where I found myself working in a journalistic Petri dish—and with the insight that 14 years has offered up—I can look at what we did, including my small part of that, and say that it was way more successful than the Wikitorial.

But, beyond my coworkers, I remember those moments of tension on the site the most, and I think the digital discourse has gone further in that direction, thanks in no small part to social media. I imagine it was the same feeling the poor L.A. Times editor who made the call to shut down the Wikitorial server felt when finding out about the kind of “user-generated content” that was actually getting generated by users.

It’s not a good feeling. And it’s, increasingly, defining what digital discourse looks like.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal! And if you’re interested in trying out Letterjoy, sign up on our Patreon page by Monday!

:format(jpeg)/uploads/tedium050219.gif)

/uploads/tedium050219.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)