Extreme Googling

It’s easy to forget given its size, but Google fundamentally changed our relationship with information. Two decades later, we’re still feeling the effects.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

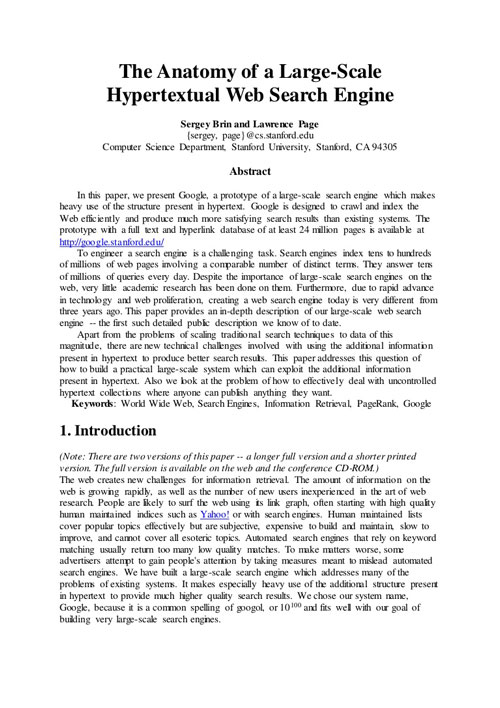

The academic paper that laid out Google’s grand ambitions

In retrospect, it’s hard to remember the search engines that Google replaced. Together, Sergey Brin and Larry Page defeated their competition so soundly and so effectively that competitors like Excite, Lycos, and AltaVista are blips in the internet’s long history, despite once being hugely important platforms.

The secret to this success is laid out in “The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine,” an academic paper Brin and Page wrote while PhD students at Stanford University.

In the paper’s introduction, they identified the larger problems plaguing search engines at the time:

The web creates new challenges for information retrieval. The amount of information on the web is growing rapidly, as well as the number of new users inexperienced in the art of web research. People are likely to surf the web using its link graph, often starting with high quality human maintained indices such as Yahoo! or with search engines. Human maintained lists cover popular topics effectively but are subjective, expensive to build and maintain, slow to improve, and cannot cover all esoteric topics. Automated search engines that rely on keyword matching usually return too many low quality matches. To make matters worse, some advertisers attempt to gain people’s attention by taking measures meant to mislead automated search engines.

The solution that the duo landed upon, the one laid out in great detail in the paper, was something called PageRank, which ranks webpages based on their overall importance in the web ecosystem, tying its results to objective rankings, not just to the ability to stuff a box full of links. The more folks link to you, the more prominent you get.

The idea was so good and so fundamental that it came to reshape the way the web worked.

(Of course, even with PageRank, there are still folks manipulating all those search terms to this day. Ask me about the people that want me to put backlinks on my old articles sometime.)

The only problem, honestly, was that the original name that the duo came up with, BackRub, was really bad. The replacement name, Google—a reference to googol, or the number 10 to the 100th power—was much better.

Larry Page and Sergey Brin, circa 2003. (Ehud Kenan/Flickr)

Page and Brin eventually left Stanford to follow the idea, building it in the rented garage of Susan Wojcicki, who later became an early Google employee, Brin’s onetime sister-in-law, and (currently) the CEO of YouTube, which Google owns to this day.

Soon enough, of course, Google would outgrow the garage, turn into a massive company, and take over our lives. PageRank was the algorithm that built the foundation of an information resource bigger than any physical library could hope to be.

The second that Google became a verb, it was clear that the company would be with us a long time, for good and for bad.

“I don’t think it’s on Viva Hate, man. We’ll have to look when I get home!”

— Musician David Rawlings, in an argument with alt-country icon Ryan Adams about the album on which the Morrissey song “Suedehead” first appeared. (The argument, famously, was captured on the first track of Adams’ best-regarded album, Heartbreaker.) Rawlings argues that the song first appeared on Bona Drag, a singles collection; Adams says it was on Viva Hate, Morrissey’s first solo album, while emphasizing that it’s also on Bona Drag, because it was a single. Adams is right (and owed $5 due to a friendly bet made during the argument), but neither can confirm it because they don’t have a smartphone or a computer nearby, and therefore no way to Google the information. (No record collection, either, to check. And Wikipedia didn’t exist back then.) The argument, one of the best parts of that album, is a throwback to the days in which people would have silly arguments about random trivia, without the ability to find things. Google would have stopped this argument, which is fun to listen to, from ever happening. But the world is better for the fact that Ryan Adams and David Rawlings couldn’t use Google in that moment.

(Eli Francis/Pixabay)

Why Google Books may be Google’s greatest disappointment

Google Books is the greatest, most hobbled research tool on the entire internet. It’s full of potential that surfaces with the right keywords. But too often, those keywords surface roadblocks.

Many of the resources gathered by the service—which was built by literally scanning books, one by one, through a number of machines—are purposely hidden from the eyes of researchers due to copyright limitations. The resulting effect is called “snippet view,” a bastardized purgatory for information in which the creator isn’t known, can’t be easily found, or for which the copyright is in limbo. I’m not a fan of snippet view, though I’ve found ways to work around it in the past.

Part of the problem with Google’s original moonshot, launched as Google Print in 2004, is that the realities of commerce and law didn’t match those of the original ambition, which was explained as such upon its launch:

Google Print finds pretty much any kind of book you can imagine: fiction, non-fiction, reference, scholarly, textbooks, children’s books, scientific, medical, professional, educational, and other books of all descriptions. With the addition of books from our library partners, our book selection will continue to increase, and you’ll also be able to find out of print, rare and public domain books.

The project, which initially was limited to book jackets and excerpts, largely fulfilled the promise of adding public domain books, but the rare and out-of-print books proved a problem, in part because of concerns about copyright.

Those concerns eventually became subject of a lawsuit by the Authors Guild, a group that represents the legal interests of individual authors and wanted to ensure that authors got paid for that moonshot. Filed in late 2005, the suit became a long-running case that lingered in courtrooms for more than a decade, becoming a defining fight for a very modern form of information consumption. (A separate lawsuit, brought by the publishing industry and led by the Association of American Publishers, was settled in 2012.)

The guild was ultimately doing right by its members, but the case was messy; a settlement decided in 2008 was ultimately thrown out, but Google ultimately won its fight to scan millions of books in a series of court decisions that finally ended in 2015.

James Gleick, the president of the Authors Guild (and coincidentally, an inspiration for Jurassic Park’s resident chaos theorist, Ian Malcolm), wrote last year that the group’s lawsuit against Google was largely “misunderstood”—that they weren’t trying to ruin the service, but simply wanted creators to benefit from the use of their content as an artificial intelligence tool that ultimately made Google better. Per Gleick:

We authors, for our part, didn’t object to Google’s creating of a search index. In itself, search had obvious benefits for everyone, readers and writers alike. We objected to Google’s seizing without permission the full texts of copyrighted books for profit-making purposes not limited to indexing and never, in fact, fully disclosed. These books are enormously valuable to anyone working on algorithmic translation and machine learning.

The result of all this legal action, however, was that it stunted the ambition of the purest expression of Google’s sheer potential as a search engine. More than any other side project Google has ever taken on, Google Books has been the closest to its general ethos. Everything that Google has taken on since Google Books—Android, Google Glass, Google Docs, the transition to Alphabet—has moved away from the idea of Google simply being the world’s best search engine. The company has greatly expanded its mission in recent years, but while Google Books didn’t look like it at the time, it was the most on-brand thing Google has ever done. Not even Gmail is as pure a play on the company’s role as information organizer.

So now, all these books and magazines sit in purgatory, never to be seen unless you go to a library and actually open up the book yourself. One has to wonder if Google would be able to salvage the project by simply handing it to a library or nonprofit so they could finish the job that Google, as one of the world’s largest for-profit companies, can’t.

On the Google Books website, the company makes a simple case that the questions of copyright that led to the Authors Guild lawsuit fundamentally misunderstand the problem the website is trying to solve—rather than trying to devalue books, the company states, Google Books maximizes that value.

“Copyright law is supposed to ensure that authors and publishers have an incentive to create new work, not stop people from finding out that the work exists,” the website states. “By helping people find books, we believe we can increase the incentive to publish them. After all, if a book isn’t discovered, it won’t be bought.”

Certainly, folks deserve to get paid, but the cost to our collective knowledge is so severe, due to the gaps left behind due to the broken nature of our public domain. If Google Books is the ultimate moonshot, snippet view is what happens when the moonshot flies too close to the sun. There has to be a way to get beyond it.

2000

The year that Google launched its self-service advertising program, Google AdWords. The program, in its initial beta form, started with just 350 companies and ad agencies, but ultimately became the main driver of Google’s business. Notably, it started out as just a text-based advertising interface, bucking a trend at the time in favor of louder and more ambitious ads. The company would launch a version of the ad platform for individual websites, which is known today as Google AdSense, in 2003. (Google reportedly gives publishers slightly more than two-thirds of the revenue earned from AdSense ads.)

A Google search box with the old logo. Since I'm here writing, can I just say that Google's old logo is something that fundamentally should not work but somehow does? It's a bad design that somehow transcends its badness. (Pixabay)

Five Google search tactics that you probably aren’t using, but should be

- Narrow by date. Google is a broad service, and a fairly deep one at that. But doing a simple search won’t always get you the best result. A good strategy for reining in its algorithm is to add a little date to the mix, particularly in regards to Google Books, so that you can get past the obvious results. The older, often, the better.

- Replace a specific site search with Google. Many websites have lame, not-useful search engines that simply don’t offer as good of results as Google does. So don’t use them! If you want to find the best results possible, use the “site” tag to narrow things down, i.e. “site:nytimes.com” or “site:disney.com”, so you can leverage Google’s search engine to get better results. Here’s an example of this kind of search from Tedium, regarding ranch dressing.

- Draw a different set of results by using incognito mode and a VPN. Google is well-known for targeting its searches to individual users, but sometimes that targeting creates a filter bubble of sorts, leading to results that it thinks you want to see. Which is sometimes great, but often can lead you to miss broader perspectives. So hop into your private browsing mode, or turn on a VPN, so that Google spits out different, more objective results. You might find something you missed the first time.

- Search by image. Google can search the attributes of an image and compare it to every other image it has indexed in its massive archive. You can literally drag an image into a search box and search against it, which may be the coolest thing Google can do to this very day. (Bing also deserves a mention here, as it recently added a feature allowing users to crop an image in real time and search against that.) Also worth trying: Simply paste the URL of an image into the Google search box to see what sites link to it. It’s worth keeping in mind that Google

- Vary your phrasing, repeatedly. The fact of the matter is, search terms are very competitive, and companies actively stuff keywords with the goal of showing up first, even if the information isn’t the best. This is something called search engine optimization, which actually predates Google but came into its own thanks to the quality of the company’s search results. As I’ve written in the past, the problem with Google is that we give up too early, rather than digging in deeper to find the best possible results. So don’t give up so quickly—if you’re not happy with a page of results, narrow down as much as you can. Quote phrases that seem relevant, and combine techniques and mediums. There’s a lot out there—and by not resting on the first result, you’re more likely to be happy with what you find.

2.8M

The number of links Google has been asked to remove from its search engine in the European Union as a result of a 2014 court ruling that’s popularly known as “right to be forgotten,” which allows people to request that links be removed from the service in the region. (Google has complied with 44 percent of such requests after review.) The European Union, spurred by France, is attempting to expand the reach of this measure to cover all Google results, whether inside the EU or not. Google is resisting, understandably.

I’m not a fan of the television showBabylon 5, but I can tell you that one of the show’s characters has a particularly relevant quote about information that sounds really good in the context of this discussion: “He who controls information controls the world.”

I can tell you this, of course, because of Google. Google is designed for making it easy to find quotes that sound good without any context around why they were said.

And Google definitely has some world-controlling powers at this point. It’s not the biggest company in the world—on Google’s 20th birthday last month, Amazon managed to upstage Alphabet by hitting a $1 trillion valuation for the first time—but its influence is perhaps more fundamental because it’s reliant on the broad spread of information, rather than the simple sale of goods.

There are lots of flaws in the way Google works. It has the ability to crush businesses, both internally and externally. As I’ve written in the past, Google is a wholesale murderer of ideas, having dropped many projects out of a lack of commercial viability or a lack of interest. The latest one, a plan to ditch Google Inbox, is like a puncture to the lung.

It’s had mixed results with its diversions; Google Maps is perhaps the company’s second-smartest idea, after Google itself, but there’s no soft-focus way to make Google+ look like a good use of the company’s resources in retrospect. They killed Google Reader, a good product with a culturally valuable fanbase, in favor of the social network version of “fetch.”

And some of the company’s endeavors, such as its AMP project to build faster mobile websites, have proven to be controversial, to say the least.

But on balance, the world is better for Google’s existence. There are folks out there that are pushing Google to be even better from the outside, such as the company’s former design ethicist Tristan Harris (who founded one of my all-time favorite startups, Apture), and competitors who are pushing against Google’s flaws, like DuckDuckGo.

But more fundamentally, looking just at the search engine that started it all and ignoring all the other bullshit that came with it, Google found success because did something that other search engines weren’t doing: It didn’t limit the problem of internet search to the internet, but approached it as a problem of general discovery. Google wouldn’t have started scanning all those books if it saw its mission as being limited in scope, like so many of its competitors did.

Perhaps we’ve lost something culturally by having all this information at our fingertips—maybe we lose out on Ryan Adams and David Rawlings debating about Morrissey at the beginning of a classic record. But on balance, the gain we’ve gotten from that is worth appreciating.

Thanks Google, even considering all your flaws.

:format(jpeg)/2018/10/tedium100218.gif)

/2018/10/tedium100218.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)