What a Wonderful World

Staffed by former Atari employees and with a big hit on its hands, Worlds of Wonder tried to ride Teddy Ruxpin to the promised land. They failed, fast.

“Having a lot of toys is not what Worlds of Wonder is about. What children gain from our toys is social value. Lazer Tag teaches them to play with each other, and Teddy Ruxpin teaches bravery and friendship.”

— Worlds of Wonder Founder Donald Kingsborough, in a 1987 Fortune article, discussing his philosophy around the toys his firm sold, including Lazer Tag, the firm’s second-biggest hit and the inspiration for a Saturday morning cartoon. In other words, Kingsborough and his company was trying to sell high-priced toys that could offer significantly higher levels of fun and engagement than cheaper alternatives. (By the way, Kingsborough is still an active executive; he spent a few years at PayPal and is now the managing director of Capital One’s venture team. Not nearly as fun as toys.)

Teddy Ruxpin may have been the first toy ever designed to be a megahit

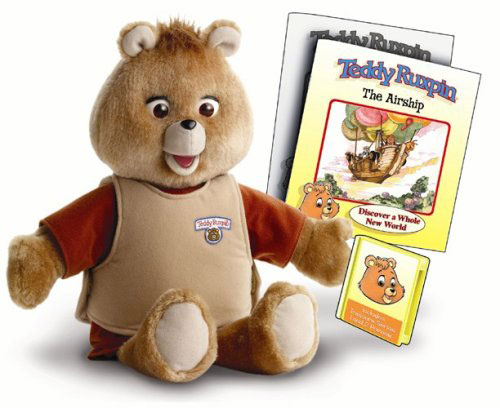

Have $70 in your pocket? That’s how much a Teddy Ruxpin doll generally cost at the time of its 1985 launch.

That cost, which would be a hard-to-swallow $156.55 today, was an immensely expensive price for a state-of-the-art toy. But tens of thousands of people paid around that much in its first month on the market, turning Worlds of Wonder into an overnight success story—one that initially didn’t have the benefit of a Saturday morning cartoon.

And the fact that Worlds of Wonder thought it could charge that much reflects two things: The product probably cost a lot to build on a per-unit basis (RKS Design, which helped formulate the talking bear, puts the cost at “under $20,“ but the fact that a design firm had its fingerprints on the product in the first place highlights that this was no ordinary toy), and it was also marketed a lot.

(It had a particularly well-considered advertising campaign that was done in a way that allowed the commercials to show up either during prime time or during cartoons—because the toy was as much for busy parents who didn’t have time to read to their kids as it was for those kids.)

But there may also be a third factor here: Teddy Ruxpin was just as much a product of Silicon Valley as it was of Ken Forsse, the puppeteer and former Disney employee who came up with the idea of Ruxpin and its creative backstory.

Part of the reason for this was the timing: 1985 was dead center in the period when video games were seen as a fad that had already passed. As a result, all these technical employees with knowledge of Silicon Valley needed something to do, so they looked at other parts of the toy aisle.

Before he started Worlds of Wonder, founder Donald Kingsborough had worked at Atari, as did many of his employees. And he wasn’t alone: His primary competitor in the talking toy space was Nolan Bushnell, Kingsborough’s old boss at Atari and a man who had experience with anthropomorphic characters as the founder of Chuck E. Cheese.

With Worlds of Wonder and Bushnell’s Axlon setting the way, it certainly felt like the start of a trend, even if it didn’t end up that way.

“Maybe ‘Toy Valley’ will become a reality here,” Kingsborough said in a 1985 interview with The New York Times.

Worlds of Wonder certainly knew the Apple-like moves. When Teddy Ruxpin became a hit, they did something that any good Silicon Valley company would do: They put their money into research and development.

(By the way, about that $70 price tag: It could have been a lot worse. According to Fortune, when the company first showed off the toy at a toy fair, it was a $150 prototype. They had to nickel and dime it into something that was at least somewhat reasonably priced.)

500

The number of Nintendo Entertainment System consoles that toy stores had to stock to get access to Worlds of Wonder’s other popular toys, according to Giant Bomb. Nintendo got around the nerves of toy stores throughout the country with this method, and within a year, the NES was enough of a hit that it could break off the deal with Worlds of Wonder. That was bad news for Worlds of Wonder.

Worlds of Wonder’s demise came about partly due to a police shooting

In 2014, a man named John Crawford III was walking around a Walmart location with an air rifle, raising concern among store-goers who called police. When they confronted the man, they believed the gun was real, shooting and killing the Ohio man and leading to ongoing protests. Crawford’s name is one of many that the Black Lives Matter movement has coalesced around.

It was a tragedy, and one where a police officer mistaking a toy gun for a real one played a factor. That led to an Ohio state representative, Alicia Reece, to introduce a bill that would require airsoft guns to have a brightly colored design that would differentiate it from a traditional gun.

Nearly 30 years earlier, a situation with many parallels to the Crawford shooting played a contributing role in the failure of Worlds of Wonder. It didn’t involve an airsoft gun, but a misunderstood game of Lazer Tag.

In Rancho Cucamonga, CA, deputies were called to investigate the scene at an elementary school after receiving a call that there were armed prowlers on the loose. The “prowlers”? A group of teens who thought it’d be fun to play Lazer Tag at night while wearing dark clothing.

One of those players, 19-year-old Leonard Falcon, jumped out in front of an officer and took a stance like he was about to fire. Problem is, Falcon had a plastic toy, but the officer had a real gun. The officer didn’t realize what he had done until after the incident—and received counseling after the fact. (He was not found liable in Falcon’s death.)

The two incidents, while having much in common, were each defined by their respective eras. In the Crawford incident, the police officers received much of the criticism from the public. But in the death of Leonard Falcon, much the blame was largely directed toward Worlds of Wonder.

The reason for this can be partly pinned to a movement that had a lot of steam in the late ’80s: The anti-war-toys movement.

In 1985, a massive campaign to stop the production and sale of war toys picked up an unusual amount of steam, with grassroots advocacy groups coming out against the likes of G.I. Joe. (Yes, this is a thing that actually happened. And yes, I need to write a full issue about it someday.)

Lazer Tag certainly doesn’t fit the definition of warfare in the modern day, but the game was lumped into the mix in part because it used gun-shaped devices and promoted the toys in a battle context, and in part because of the toymaker’s response to the shooting, which did them no favors.

Worlds of Wonder chose not to comment on Falcon’s shooting when it took place, and when called by Jerry Rubin, the Southern California coordinator for the National Stop War Toys Campaign, he said that he was “shocked by their insensitivity” to the incident.

“When I offered them Falcon’s family’s phone number, they said no,” Rubin told UPI in 1987. “The brutality and realism of offering these types of toy guns to children and teens is crazy and will only lead to more incidents like this.”

The shooting was believed to be a contributing factor to the demise of Worlds of Wonder, which first filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy just eight months later, and shut its doors for good in 1990.

So why did Tiger Electronics earn its golden parachute while Worlds of Wonder failed to even make it past its third Christmas without a bankruptcy?

There are a lot of factors at play, including the bad press of the story I highlighted above, along with some bad moves on the stock market that led to the company’s stock price being exposed to the market forces of Black Monday. (Also, accepting $92 million in debt, as WoW did, is a Bad Idea that will lead to litigation.)

But strangely, the biggest factor may have been too much innovation, too fast. The company’s decision to reinvest its Teddy Ruxpin money into new products meant that it had a lot of new products hitting the market all at once, but they weren’t big hits like Lazer Tag or the NES; nobody was buying them.

As a kid, I remember having one of WoW’s biggest duds, an unusual VHS-based video game console called the Action Max. The system used light guns, like Nintendo did, but the console basically had you shoot at the screen while a pre-decided video was already playing. It may have been the worst idea for a video game system I’ve ever tried, and that’s saying something because I’ve played the Virtual Boy before.

But Tiger had plenty of bad ideas like this (looking at you, R-Zone), and they never took down the company, because they could always rely on their LCD consoles.

Could it be that Worlds of Wonder simply needed to sell more crap? God, I hope not.

:format(jpeg)/2017/06/tedium090916.gif)

/2017/06/tedium090916.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)