We All Make Mistakes

If you make a mistake today, don't fret. Everyone else around you has made a bunch, too. Errors, in a lot of ways, give us our wrinkles as human beings.

"Broadly speaking, when humans do simple mechanical tasks, such as typing, they make undetected errors in about 0.5% of all actions. When they do more complex logical activities, such as writing programs, the error rate rises to about 5%. These are not hard and fast numbers, because how finely one defines reported 'action' will affect the error rate. However, the logical tasks used in these studies generally had about the same scope as the creation of a formula in a spreadsheet."

— University of Hawaii Professor Raymond R. Panko, discussing the commonality of errors made by humans in his 1998 paper What We Know About Spreadsheet Errors, which he most recently updated in 2008. Panko, an information technology management professor at the school's Shidler College of Business, runs a website dedicated to the nature of human error, complete with theories on the cognitive processes that lead us to make mistakes. "Corrections are appreciated," he writes on the front page of the site.

When mistakes accidentally end up in the dictionary

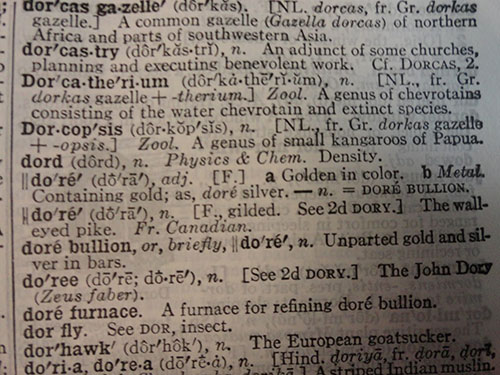

Bad news, Scrabble fans. If you ended up using "dord" in a recent round of the game, you need to hand back those points.

However, it should be noted that you probably should update your dictionary, stat. For five years, the unusual word, claimed to be a scientific term for density, was a part of Webster's New International Dictionary.

The reason that the word showed up in the dictionary is actually pretty entertaining. One day, Webster's chemistry editor Austin M. Patterson sent a note to the book's printers noting that the word density could be abbreviated as "D or d" when used in the context of physics or chemistry. The printers misunderstood what Patterson was trying to say, and … well, they invented a new word. Oops.

After the error was discovered in 1939, Philip Gove, the editor of Merriam Webster, revealed what happened.

"As soon as someone else entered the pronunciation," Gove wrote, "dord was given the slap on the back that sent breath into its being. Whether the etymologist ever got a chance to stifle it, there is no evidence. It simply has no etymology. Thereafter, only a proofreader had final opportunity at the word, but as the proof passed under his scrutiny he was at the moment not so alert and suspicious as usual."

The fun part about all this is that dord arguably should be in the dictionary—just not as a synonym for density. See, "dord" is actually the name of an ancient musical instrument in Ireland, a giant horn best compared to the modern didgeridoo. It dates back to the Bronze Age. (In case you think I'm BSing you, here's a video of a guy playing the instrument in his kitchen.)

Sounds like someone made a mistake.

$12.7M

The amount that an errant "s" on a liquidation notice cost the U.K. government, after Companies House, a federal agency, accidentally announced the liquidation of "Taylor & Sons," rather than "Taylor & Son." The former firm was admittedly struggling at the time, but was holding on. But the announcement actually turned into a self-fulfilling prophecy, leading to the firm's shutdown not long after, leading to the layoff of 250 employees. The owners of the company sued—and won.

(via Buzzfeed)

Why we're happier with things we do ourselves, even when we do them incorrectly

Ten to one, there's probably a piece of furniture in your house or apartment that feels a little loose. On the surface, it looks fine, but it's not fully put together … maybe a screw's missing, or you had an unexplained missing part after the fact.

It translates a lot of other places, as well. Say you paint something or put a lot of work into a weekend project. The result may not be technically good, but you personally appreciate the effort you put into it, and see it through the prism of the fact that you made it, and therefore, it's awesome.

Turns out, there's actually a term for this phenomenon. It's called the IKEA Effect, a form of cognitive bias that has gained a bit of currency over the past few years. The idea was first brought about by a trio of professors—Harvard's Michael I. Norton, Tulane's Daniel Mochon, and Duke's Dan Ariely—who published their findings in the Journal of Consumer Psychology in 2012.

The abstract of the research paper nails the basic issue at hand:

In a series of studies in which consumers assembled IKEA boxes, folded origami, and built sets of Legos, we demonstrate and investigate the boundary conditions for what we term the—"IKEA effect"—the increase in valuation of self-made products. Participants saw their amateurish creations—of both utilitarian and hedonic products—as similar in value to the creations of experts, and expected others to share their opinions. Our account suggests that labor leads to increased valuation only when labor results in successful completion of tasks; thus when participants built and then destroyed their creations, or failed to complete them, the IKEA effect dissipated.

The result is that we like and may even defend the final result of what we were working on, despite the inherent flaws and inconsistencies we may be baking into the process along the way.

So, if you're making a poster and don't really have any experience with design for example, you may not be aware of what kerning is and why it's a beneficial part of designing something reliant on typography. But a designer? They can spot it from a while away, and they realize that (in their line of work, at least) it's an error.

If that designer goes up to the person who made the poster and tells them, hey, your kerning looks janky, they might get upset with you, even though the result is technically an "error" or a "mistake." Because, ultimately, when it's our work, we appreciate the final result more.

In a TEDx talk Ariely gave, he admitted that "mistakes" ultimately gave the IKEA pieces he built their charm.

"I can't say I enjoy those pieces. I can't say I enjoy the process," he told the audience. "But when I finish it, I seem to like those IKEA pieces of furniture more than I like other ones."

"Literally for hundreds of years, we have been promising readers when we make an error we correct it. That's how it works with newspapers. … Then all of a sudden because it's easy to scrub something away, we are abandoning what we've been doing for hundreds of years. It's really shameful. It seems to make journalists and editors forget this standard that we've had for such a long time."

— Craig Silverman, the founder of the news blog Regret the Error, which is now owned by the Poynter Institute, speaking about the importance of correcting errors in a 2010 interview with the American Copy Editors Society. Silverman, who now works as an editor for BuzzFeed, has become something of a key figure on the importance of corrections, something he believes is getting more important in the viral news era.

As I think I've said before, my favorite movie is The Room. It probably always will be. It's perfection on celluloid.

But the thing that makes it perfect is that the fact that it is so raggedly, horribly, awkwardly human—the work of Tommy Wiseau, a man impossibly out of his depth as a filmmaker, actor, and writer. And as a result, it's full of errors, large and small—more than a lot of films of its ilk.

The IMDB page is, as a result, one of the funniest pages on the site, because it shows the depths of the film's failings.

At one point, Wiseau's character, Johnny, makes a claim that when he first got to San Francisco, that he couldn't cash a check because it was from out-of-state—which, as the IMDB page notes, is something that you can, in fact, do, and something Johnny should know, because he works at a bank.

There were other major plotting errors (dialogue in a pivotal early scene makes reference to nonexistent candles and music), along with problems with the set (characters on the second floor have to first climb up stairs before going down a spiral staircase), continuity in filming (watch this YouTube clip), and problems with the casting (there's a "Barista #2" listed in the credits, despite the fact that there is no "Barista #1"). The movie is perhaps littered with more errors than any other movie of its ilk, cult audience or not.

But without those errors all over the place, the film would not have any of the ramshackle charm that makes it worth going back to.

Don't tell your grammar school teacher this, but errors are the spice of life. Well, at least in some contexts.

:format(jpeg)/2018/01/heqmpwtqcyrxvvau705j.gif)

/2018/01/heqmpwtqcyrxvvau705j.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)