No Vacancy

Hotels are bastions of consistency, especially when it comes to the amenities. But with Airbnb out there, is hotel psychology losing its grip on travelers?

“In the United States, toothpaste falls under a more rigorous set of regulations than shampoo or soaps; it’s treated like a drug. As such, it must be produced according to the government’s rules for ‘good manufacturing practice,’ which can increase the cost by 30 percent or more.”

— Slate writer Daniel Engber, discussing one theory why you’re unlikely to find toothpaste in hotel rooms, despite the fact that other main toiletries like soap and shampoo are handed out like it’s no big thing. But Engber notes that this theory is not accepted across the board—one longtime hotel-industry worker that spoke to him argued that this wasn’t the case, but rather that it’s not enough of a status symbol to be worthwhile for hotels.

Why hotels were perfect vessels for introducing wireless access

Hotels were one of the first places where many people ran into WiFi in public, and it shows. When you stumble into a hotel network and log in, you might run into confusing, ugly login screens with limitations and regulations on how you can use that dangerous connection to the internet they’re arming you with.

To this day, hotels have a mixed relationship with wireless internet access. Only within the last couple of years have luxury chains generally made wireless access available for free, and at times, some of those chains have been the target of some not-great headlines due to the way they regulate that access.

In this context, it may be hard to remember that hotels were at one point front-running innovators in the wireless space, launching the underlying networks years before you’d run into them anywhere else. While most of us were still using dial-up modems to get online, major hotel chains were serving up ethernet-level speeds, first through actual cables and later through wireless networks.

They had a good reason to get out front on this trend: Their guests are often road warriors, the kind of people that went to conventions and needed to remind the home base that they were still on the grid even if they weren’t in the office physically. And as a result, they had laptops, cell phones, and personal digital assistants years before everyone else.

In other words, hotels were the perfect audience for WiFi. Now, there were early examples of WiFi in the public square, most notably Carnegie Mellon University’s Wireless Andrew network, which was active as early as 1993.

But as far as normal people getting on the internet without any wires, that didn’t happen until the turn of the century, really.

The rise and fall of the first hotel wireless company (and how Steve Jobs sold WiFi with a hula hoop)

Perhaps the first key moment in WiFi’s takeover came about in 1998. That was the year that Hilton scored a deal with to bring wireless access to some of its hotel locations.

The company worked with a firm called MobileStar, which was launched with the goal of taking wireless internet mainstream. The hotel giant’s agreement wasn’t completely unique—another competing firm, Suite Technology Systems Network (STSN), came about around the same time and later helped Marriott get online, while a third firm, Wayport, worked with a number of other hotels. (Wayport, now owned by AT&T, famously got McDonald’s on the internet.)

But MobileStar was able to strike so early that the industry didn’t even have the branding for WiFi down yet. (That didn’t come until 1999, thanks to the help of a branding company.)

“We think making wireless computer communications possible will create a huge demand in a very short time. We’re calling it ’The Portable Internet,’” MobileStar CEO Mark Goode said at the time the deal was announced.

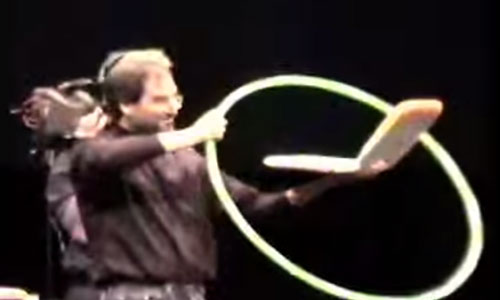

At first, the awkwardly named “Portable Internet” was mostly made up of computers with add-on PC cards. But in 1999, the concept had a public coming-out moment, when Steve Jobs revealed the Apple iBook to the public. Ever the showman, Jobs used a hula-hoop to prove that the iBook was connected to the internet without wires.

Partly as a result of that eye-catching display, it was only a matter of time until WiFi was off to the races. Soon, other laptop-makers included it as a default option. And MobileStar was doing its part by expanding its network of hotspots. In 2001, the firm scored a deal with Starbucks and was building out wireless access at a number of the coffee shop’s locations, and it already had a strong base in a number of airports. It wasn’t cheap—the service cost $30 a month—but it was very much a first-mover kind of service.

But MobileStar was a startup working in a post-bubble era—particularly in a space, business travel, that had been negatively affected by the September 11, 2001 attacks—and it ultimately wasn’t able to hold on. In early 2002, the company laid off its employees and abruptly shut down its services. The disruption was so unexpected that hotels that relied on its service saw the network go down without any warning.

The firm eventually went back online, but soon was sold to the company that became T-Mobile, which runs the network to this day (although it lost the Starbucks deal back in 2008).

In the end, MobileStar’s work was important. While the company itself was chewed up and spit into the merger abyss, it set the stage for the always-accessible internet we’ve come to expect. We left it to others to make it free.

68°

(Elizabeth Greene/Flickr)

Five ways hotels use subtle psychology to shape your experience

- Website design: Your average hotel website is full of small cues to keep pushing you forward, small things to guide you through the process. Think points of urgency, design predictability, things like that. The goal is that, once they have you hooked, they don’t want to lose you as a customer.

- Simple choices: Hotels attempt to take a lot of the decision-making process out of the guests’ hands at every part of the process, from the reservations on down. This helps boost the comfort level. “If you do it right, then hopefully you get that big ‘sigh moment,’ when the guest says: Yes. They really get me. They understand what’s important to me,” hospitality consultant Andrew Freeman explained to Psychology Today. (If you know anything about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, that’s be basic concept that we’re talking about here.)

- The headboard: In budget hotels in particular, hotel designers will splurge on a fancy headboard. The reason? According to The Daily Mail, they stand out when you first walk into the room—and tend to take the attention off the shabbier pieces of furniture elsewhere in the room.

- Thread count: The Daily Mail piece notes that we ultimately decide on whether a hotel is awesome or not based on how we slept—and as a result, a lot of hotels up the thread counts on their sheets to help keep the bed extra comfortable. You’ll find 600 thread count sheets in the nicest hotels.

- Towel use: In recent years, you might have spotted notes near the bathroom telling you to be thoughtful about your towel use so as to save water. Crazy as it sounds, this strategy actually works—a 2013 study found that when people were told that previous guests in the room had reused their towels, they tended to use fewer towels themselves.

“The designer would say ‘Send me a catalog!’ And we would literally mail them hundreds of catalogs and they would choose the image based on that. But now, with the digital age, all the items are digitized, so you can make whatever color you want, whatever size you want, and you can print them on whatever you want.”

— Puneet Bhasin, COO of the Artline Group, discussing with Marketplace the process that hotel designers use in choosing hotel art. His company, as you might guess, specializes in selling such art to hotels around the world—working with interior designers to help set the tone of a given hotel. One issue that Bhasin’s firm has to help designers avoid is the issue of not putting the same artwork in different hotels, so as not to drive the road warriors crazy.

In the age of Airbnb, it’s worth pondering: how important are all these amenities, really? You could always just buy a 288-pack of hotel-size shampoo, carry a handful with you during long trips, and be done with it.

That sounds a bit flip, admittedly, but on the other hand, Airbnb probably exists as a reaction to the overly perfect feel of hotel rooms around the world. In many cases, hotels feel antiseptic and over-designed. InformeDesign, an educational resource for interior designers, noted in 2005 that this problem is nothing new for big hotel chains, who dealt with the problem previously by pushing things over the top.

“Hotels were designed to support the most basic of needs,” Domus Design Group’s Bruce Goff wrote at the time. “Then, over the last seven years, hotels found that they were losing market share to smaller, more personal hotels and responded, not with personality, but with higher standards.”

The hotel industry has not been happy to see the rise of Airbnb for a lot of reasons, but I have to wonder if one of them is the fact that the startup’s track record of success suggests that we’ve been broken of the spell of consistency that we’ve come to expect from our lodging experience.

Or maybe Airbnb is simply pointing out that there’s an audience for people who like imperfection, or at the very least something off the beaten path. That’s OK, too.

:format(jpeg)/2018/01/rv0u2m5g0i2pi4fewjtl.gif)

/2018/01/rv0u2m5g0i2pi4fewjtl.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)