Let's Bowl 'Em Over

Could cereal's waning popularity in the United States have something to do with a lack of exotic options? Let's look at what the rest of the world is doing.

Soylent Has Some Competition

As we've covered previously, Kellogg's past is full of healthy history—specifically when it comes to the meat analogues the company still sells under its MorningStar Farms brand. But none of the cereals currently made by the Michigan mush-maker currently go so far as to market themselves as a "meal replacement in a bowl." Well, in the U.S., that is. You have to look north of the border for that—specifically, to Canada, where Kellogg's sells a very muscular cereal, VECTOR*, that stakes this claim. The mix of crunchy flakes and granola clusters (which any discerning consumer could tell you sounds awfully similar to Honey Bunches of Oats) packs 13 grams of protein, 54 grams of carbs, and 22 vitamins and minerals into a single skim-milk-mixed bowl.

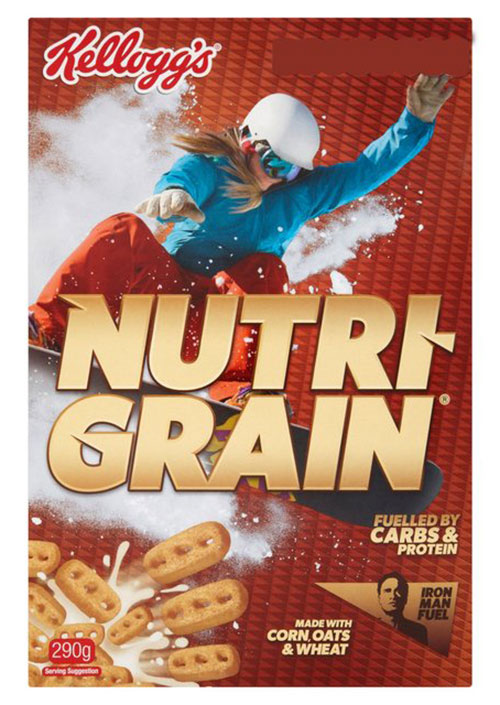

Nutri-Grain, in Cereal Form

In the United States, Kellogg's Nutri-Grain cereal bars get a bit of a bad rap among health advocates—critics say that it represents one of the worst examples of an unhealthy product sold using healthy language. (The cereal giant defends its work, once pish-poshing a class-action suit over the issue.)

That's interesting and all, but what's perhaps more interesting is that in Australia and New Zealand, Nutri-Grain cereal (yes, cereal) is promoted basically the same way you'd expect Wheaties to be in the United States—generally with an athlete or medals of some kind on the front of the box. There's a reason for this: In 1984, Kellogg's started sponsoring a multi-discipline water sports endurance event called the Nutri-Grain Ironman Series, giving the event its name for more than 30 years and ensuring that the cereal would always have a place on Aussie shelves.

Problem is, even with the athletes and medals on the front of the box, it still nonetheless doesn't hide the fact that the cereal is unhealthy. In an analysis by Australian health officials released last year, the corn, oat, and wheat mixture received one of the lowest possible scores from the country's five-star rating scheme—a mere two stars, which won't look good next to those athletes. (It explains why the company reformulated the cereal late last year.)

The shape and flavor of Nutri-Grain may change, but its nutritional issues stay the same, apparently.

Five interesting quirks you'll find with cereal worldwide

- Manufacturers have been trying to make cereal a thing in Japan for more than 50 years at this point, and initially failed—early on, cereal was a common sight in the candy aisle, rather than the breakfast aisle. But slowly, it's caught on. A 1990 Los Angeles Times story found that cereal was finally becoming big business in the local market. In 2014, meanwhile, granola became a full-on trend in Japanese households, helping to drive double-digit growth in the cereal space.

- It's common for downmarket brands of cereal to sell in bags rather than boxes in the United States, but outside of the U.S., it's common to see top companies sell cereal in inexpensive plastic bags. For example, Alimentos Granix was the top seller of cereal in Argentina in 2015—outdoing Nestlé and Kellogg's—but the company still uses bags.

- While cereal generally tends to be a game of globalization—Nestlé and Kellogg's, mostly—there are some local companies that make their own kinds of cereal. One particularly interesting example comes from Lithuania, where Cerera Foods became a well-known manufacturer after launching in 1995. While mostly targeting kids, they also sell a coffee-flavored wheat cereal. (!)

- Sometimes, popular brands of cereal stick around in other markets even if they fail in the U.S. for some reason. A good example of this is Oreo O's, a popular brand of cereal that came about due to corporate synergy—Kraft owns Oreos and, at the time, owned Post Foods. But when Kraft spun off Post in 2007, the corporate synergy was lost and Oreo O's faded from view. But in South Korea, far from all that corporate synergy, the cereal was made for another seven years by a local company called Dongsuh Foods that had the legal right to work with both companies. However, the cereal was discontinued in 2014 after the company faced a contamination scandal. Sorry, guys.

- And like fast food, you'll occasionally run into a variant of a popular cereal that's only available locally. A good example of this is Frosted Flakes, which long had a chocolate-flavored variant, Choco Zucaritas, available in Mexico. People heard about it, and Kellogg's brought it to the U.S., where you can buy it at Amazon, complete with its original Spanish name in smaller type. One kind you won't find in the U.S., however, is Choco Zucaritas con Malvaviscos, which adds marshmallows to the mix.

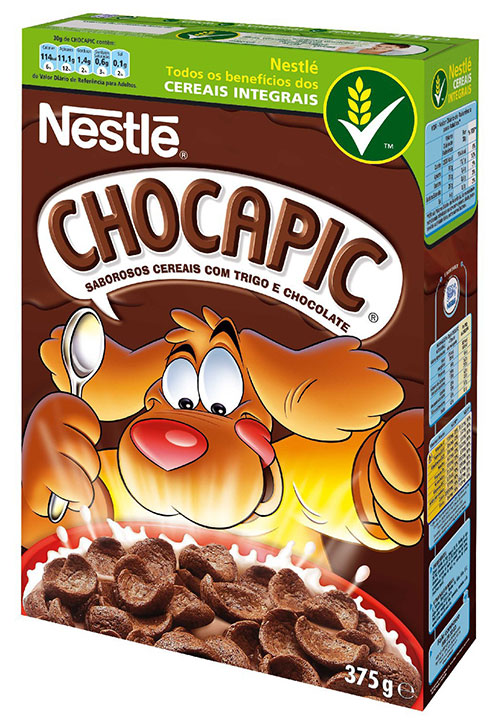

Cocoa Overload

Outside of the United States, Nestlé is a cereal tour de force—something easily proven by the success of its Chocapic cereal, which is common in much of Europe and Latin America. The cereal's commercials follow similar cues to a lot of sugary cereal brands Americans are familiar with—anthropomorphic cartoon animal, usually shown with a kid, getting real excited about the cereal they're talking about, usually with some sort of adventure driving the ad. The cereal itself, speaking purely in American terms, is a pebble-style treat that's something of a combination of Cookie Crisp (in that the texture is similar) and Cocoa Pebbles (in that it's doused in chocolate powder that ensures you'll soon have chocolate milk).

In some markets, however, the cereal takes on a different name, Koko Krunch, though the style is otherwise the same. Last year, the Minions helped promote the Koko Krunch in Malaysia.

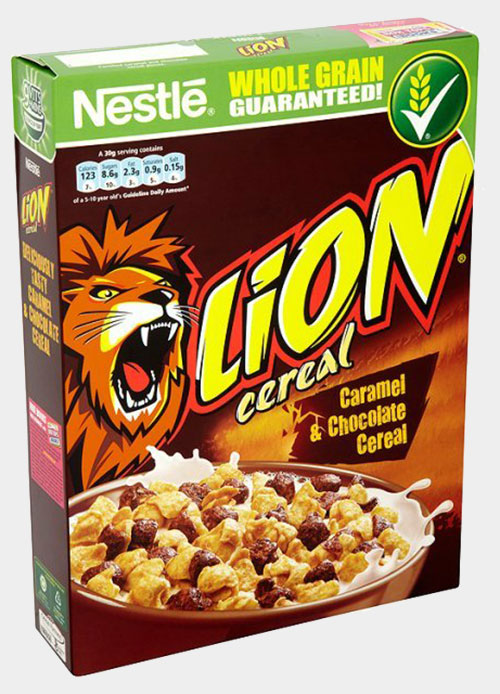

Lion's Sugary Roar

Another Nestlé brand largely sold in Europe that deserves a try in the American market is Lion Cereal—which is based off of the hugely popular candy bar that sports a style roughly akin to what you'd get if you combined a 100 Grand bar with a Kit Kat bar. Nestlé first put the cereal on the market around 2000, but stopped selling it for a time—potentially because the cereal was found to be the unhealthiest for sale on British shelves. It came back with a reformulated version a few years ago that does slightly better on the nutrition front.

But by no means is this cereal healthy, but unhealthy just means it tastes better! Some American expats have come to love this cereal so much that they've created their own profane commercials for it.

(Nestlé knows a thing or two about synergy, particularly between its candy bars and cereals. The company a couple years back also released a cereal based on its popular Toffee Crisp bars.)

“We’re having a think about what we’d add to Weetabix to make it savory. In the same way as we’ve added chocolate chips or golden syrup or banana to cereals here, you could add other savory flavors, like green tea, sesame seeds, cranberries and other fruits.”

— Giles Turrell, the CEO of Weetabix, discussing the long-time British brand's efforts to enter the Chinese market. Weetabix, which has long been sold in the United States and other countries though has remained a less-prominent part of the cereal aisle outside of the U.K., is now fully owned by the state-controlled Chinese firm Bright Food. One problem: Chinese culture isn't so hot on sugary breakfast cereal. As a result, the company has embraced green tea, fruit, and even salt and pepper in an effort to make the cereal palatable to the market.

If you're interested in seeing a random cereal from another country end up on your breakfast table, it's not easy. You'll have to do a bit of digging around. There will likely be shipping costs, and possibly even import costs. Lion Cereal, for example, can be found on Amazon, but good luck finding Kellogg's VECTOR* in the U.S.

That said, sometimes if there's enough interest or even a natural product connection that can interest cereal-makers into bringing a product stateside. Back in 2012, Kellogg's brought the chocolate-packed Krave to the U.S. after a solid early run in the U.K., proof that if there's a market for an international variety of cereal, the cereal companies will be willing to import all these esoteric brands and make them locally.

Now, of course, all we gotta do is get the snake people on board.

:format(jpeg)/2018/01/e8qxrbqvz0vvi1nhoqim.gif)

/2018/01/e8qxrbqvz0vvi1nhoqim.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)