Deep Dish

For a short period in the early 1980s, giant satellite dishes ruled the land. It was a rare moment when big telecom wasn't in control. That quickly changed.

$36k

The price of a backyard satellite dish advertised in a 1979 Neiman Marcus catalog—the first such dish sold commercially. Soon, the prices went down significantly, especially after the Federal Communications Commission deregulated the usage of such dishes, which used the open-air C-Band range of wireless signals, so they could be used by more than cable companies. A 1981 New York Times article noted that dishes could be had for as low as $3,000; a 1985 piece cut that price down to $1,500.

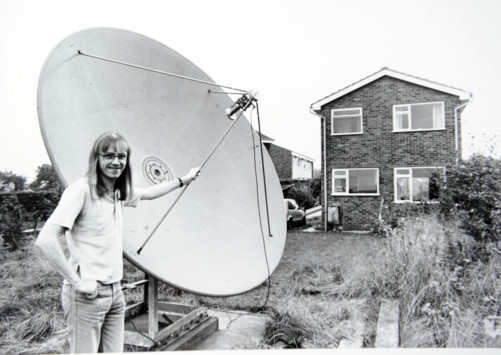

The guy who built his own satellite dish on his kitchen table

In the 1970s, the odds of seeing a television program designed for another country were extremely low—especially if you didn’t live near that country’s border. But when British man Stephen Birkill heard that NASA was delivering educational literacy programs to rural India via satellite, he had a hankering to see what they were like.

Birkill, fortunately, was the kind of person who could figure out such a task. He was a tinkerer who already managed transmitters as a BBC employee. Inspired, he decided to attempt to build his own dish and point it in the general direction of the satellite broadcasting the program.

Because satellites often have a huge amount of reach, this was actually a lot easier than it sounded. It just required him to spend his weekends building a homemade receiver of his own that could pick up the signal.

“I knew there was a future in satellite television,” Birkill told The Star. “It was a gut feeling that gave me the inspiration. I had done the sums and I knew that it was technically possible, I just had to prove that it was practically possible.”

Birkill’s device—which required him to manually aim the satellite in the general direction of whatever channel he was trying to view at the time—worked, and it opened up a new world of television options for him and his family. He was so early to the game that broadcasters hadn’t considered that someone might want to do this.

In a 1982 episode of the BBC’s “Blue Peter,” he showed off both the technology and the aim needed to get the dish working—then impressed the heck out of the host by getting some Russian television on the telly.

He also predicted that within a decade, small satellite dishes would be available in homes around the UK. With the launch of Sky TV in 1989, he was right.

“A certain percent of those people who bought dishes in the early days were the ‘daredevil’ types. They got a thrill out of taking something away from HBO. But you knew it wouldn’t last.”

— Norman Goldberg, a satellite salesman in Columbia, South Carolina, discussing the changing nature of the satellite dish industry in a 1990 interview. Goldberg says that he was aware that broadcasters eventually planned to scramble their signals—something allowed by the passage of the Cable Communications Act of 1984—and he never misled his customers on that point. Still, the reckoning—which started in early 1986, when HBO decided to scramble its feed—ticked off a lot of folks. “As soon as the scrambling started, those people lost interest. I remember a lot of people with dishes got mad and it scared off others who were thinking about buying a dish,” Goldberg said.

Captain Midnight: The folk hero satellite fans needed

If you’ve heard of “Captain Midnight,” there’s a good chance that you’ve heard his story as a secondary tale that gets passed along with the more-famous “Max Headroom Incident.” The latter incident was a dadaist work of shock art that featured a fly swatter, a brief moment of nudity, and some effective usage of corrugated metal. You see that stuff on the internet by accident nowadays, whether you’re an Ashley Madison subscriber or not.

But Captain Midnight’s big moment was a pretty solid middle-finger from C-Band owners to HBO, who had plenty of reason to be upset. They spent thousands of dollars buying their own equipment and setting it up, only to find out that HBO was gonna start scrambling its damn signals anyway—charging satellite owners more than some cable subscribers were paying at the time.

The signal-scrambling was a double-whammy for satellite owners, who had already spent thousands of dollars to avoid fees, only to find out that HBO was gonna force them to spend to spend hundreds more on descrambling equipment, all for the right to pay a subscription for HBO. In one fell swoop, HBO made a sound investment for TV fans who didn’t want to have to pay a monthly fee a lot less appealing.

John R. MacDougall, who had built a satellite TV business in Florida, was particularly smarting because of this—and for good reason, because it was the initial catalyst that led to most other satellite broadcasters to begin scrambling their signals, too. HBO’s move was the first step towards subscription satellite service, and their move would eventually make C-Band satellites a lot less useful. And—unlike the current battle over net neutrality—the FCC was on the broadcasters’ side.

One night, MacDougall used his telecom skills and access to take a shot at the pay-TV giant. While working a secondary job monitoring the feed of a pay-per-view satellite signal, he decided to use the signal he had at his disposal to outpower HBO’s own satellite feed. He put up a message, printed in white letters over a test feed, with a simple message of protest: “$12.95/MONTH? NO WAY! [SHOWTIME/MOVIE CHANNEL BEWARE!]”

The signal override, which took place just after midnight on April 27, 1986, was only four-and-a-half minutes long and didn’t cause much damage besides annoying a handful of people who really wanted to see The Falcon and the Snowman. But the situation was so unusual that authorities were worried that they were dealing with a domestic terrorism threat, rather than a harmless protest by a guy whose livelihood had been endangered by HBO’s aggressive pricing strategy.

The reason was that, as a 1986 issue of Mother Jones notes, was that MacDougall accidentally exposed a major flaw with the satellite system as a whole. And he had a satellite powerful enough to jam military defense systems.

“It was video terrorism all right, but Showtime and HBO are the least of the worries,” Donald Goldberg wrote in his piece. “Massive amounts of sensitive Defense Department information are carried along the same satellite networks that MacDougall exposed as vulnerable to the acts of satellite saboteurs. This information, ranging from encrypted telephone calls to routine orders, is at the mercy of any Captain Midnight with more on his mind than satellite scrambling.”

MacDougall eventually was caught through a process of elimination—there were only so many satellites out there that were powerful enough to stop HBO’s signal, and most of them weren’t being used for nefarious purposes that night. Still, when he was finally caught, he only received a $5,000 fine and probation—probably avoiding a larger sentence because he committed the act before the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act became law in October of 1986.

To this day, he defends what he did, though he admits he wish he had been smarter in the ways of the media.

“I do not regret trying to get the message out to corporate America about unfair pricing and restrictive trade practices,” MacDougall told NetworkWorld in 2011. “That was the impetus for doing what I did; that’s the reason I jammed HBO; that’s the reason I sent them a polite message.”

He was just protesting with the tools he had in front of him—nothing more, nothing less.

“One of the great things about commercial DSS satellite television is that you can watch it without having the remotest idea of how it works. This is not a luxury afforded to viewers of free-to-air content.”

— Steven William Rimmer, a free-to-air satellite enthusiast, discussing the nature of non-encrypted satellite content in a lengthy article on the Alchemy Mindworks website. If you’re thinking about buying and installing a giant dish in your yard, you have options for watching stuff on free-to-air satellite television even now—just don’t expect the stuff that you’ll find on most cable systems, and open your mind to some different options. Rimmer’s guide is a great place to get started with your aspirations to hook up with generation-old technology.

If you’re stuck with a giant C-Band dish in your yard for some reason—odds are good for that if you live in West Virginia, where they were so popular that they were jokingly called the official state flower—all is not lost for your old dish. One Instructables user came up with a novel way to reuse a C-Band dish as a solar-powered water heater. The dishes are also perfectly sized to turn into a birdbath or small pond.

“One man had made an ornamental fish pond for his front lawn,” waste activist Karen Engle told The Associated Press in 2001. “He dug a hole and put the dish inside and lined the top with rocks. It worked well.”

And based on this Pinterest page, there are plenty of satellite dish gazebos out there.

But perhaps the best idea for satellite reuse is as a WiFi signal transmitter. Because the dishes are so large, they can expand the reach of a WiFi signal to literally miles in reach. Even old DirecTV and Dish antennas can help extend WiFi signals as far as 8 miles away, given the right circumstances.

The downside is that the path has to be free of obstructions, but if you live in an area without a lot of forests or hills, it’s a great way to turn that old metal flower into something slightly more useful.

:format(jpeg)/2018/04/mecyk6p0cbo9gh0zyrdd--1-.gif)

/2018/04/mecyk6p0cbo9gh0zyrdd--1-.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)