Big in Brazil

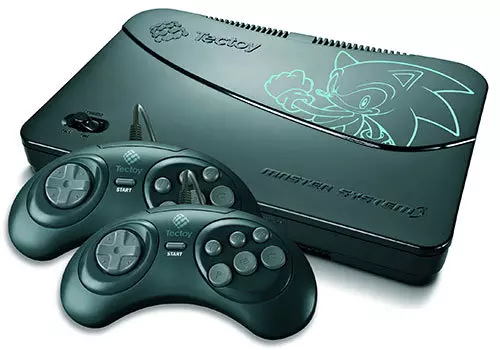

The Sega Master System was an also-ran in the United States, but in Brazil, it's still on the market—and still moving units. Here's how it happened.

5M

But why is the Master System so popular in Brazil?

There are a number of reasons for this, but it basically comes down to a canny partnership on the part of Sega, who found the market relatively early and never really let it go. Here’s what’s keeping the Master System alive:

Good timing: While the Master System was technically a more powerful system than the Nintendo Entertainment System, Sega was constantly playing catch-up to Nintendo in the United States. It didn’t have the games everyone wanted because Nintendo had exclusive licenses with nearly every large game maker of the era. But Nintendo had ignored Brazil, a country with roughly two-thirds the population of the U.S. but nearly as much interest in games. Sega, on the other hand, had built a licensing agreement with Tectoy, a local toy manufacturer. That agreement ensured the Sega would always have a backer in Brazil. And because Nintendo had ignored the market at first, NES piracy was rampant by the time it got there.

Nostalgia: Gamer memories of the Master System in Brazil rival those of the NES in the U.S., and because Sega eventually got out of the market for building new consoles, Tectoy was essentially left to market the Master System and Mega Drive (which you might know as the Genesis) by its lonesome. Rather than giving up on the system, the company adapted its approach, coming out with continually updated versions of the device and even producing new games long after the system had faded from view everywhere else.

Excessive import taxes: Around the time of the Playstation 4’s launch, it was revealed that Sony’s console had a pretty insane price for the Brazilian market. At a time when the system was selling for $399 in the U.S., an equivalent system was heading to Brazil for $1,899. “It’s not good for our gamers and it’s not good for the PlayStation brand,” Sony admitted, but said its hands were tied due to insanely high import taxes. Tectoy, meanwhile, doesn’t have this problem, because it produces the systems locally, meaning that you can get a Master System with 132 built-in games for around $50 in U.S. money at Walmart—a steal compared to the $712 price of the PS4 now.

“Buying original games in Brazil is so expensive that [it] even frightens. To give an idea, a just-launched game can cost up to BRL 250 in the country, almost half of the workers’ minimum salary. That explains why, according to surveys, Brazilians prefer to buy their games on travels abroad or from illegal sellers.”

— Juliana Mello, a writer for The Brazil Business, explaining how the country’s import laws limit the reach of modern games. Brazil is one of the largest markets in the world for video games, but because of a set of strict import taxes designed to ensure that locally built products get preference in the market, piracy has become rampant. Microsoft got around this problem with its Xboxes by creating factories to build consoles locally. As a result, the Xbox One, while still more expensive in Brazil than in the U.S., is still more than $100 cheaper than the cost of Sony’s Playstation models. (By the way, the exchange rate between the Brazilian Real and the U.S. dollar is 1 real for every 31 cents—so a single video game generally goes for around $80 in Brazil.)

There’s an 8-bit version of Street Fighter II made specifically for Brazil

Street Fighter II is the ultimate 16-bit game. The 1991 quarter-muncher was colorful and sorta violent, but not to the point where playing it would get the moral police on you like Mortal Kombat or Night Trap would. It also was one of the first games that showed a large number of gamers how awesome an arcade game could be with a ton of buttons. It had fluid animation and definitely used all 16 of those bits.

But despite all this, Tectoy still figured out a way to make it work on an 8-bit console, giving Master System owners a taste of a game on a machine that had no business playing it. How’d they do it? Well, they took out all the graphical details, some of the enemies, and much of the frame rate.

If you wanna see what I’m talking about, here’s a YouTube clip of the arcade version of Street Fighter II. Watch that, then watch this clip of the Master System version. Big difference—right? Now just imagine playing this game with a two-button controller without wanting to gouge your eyes out.

“Street Fighter 2 for the Master System will always stand as one of the worst ports of all time along with Pacman for the 2600,” wrote GameFAQs reviewer AlCurtis. “It’s incapable of running on the hardware and should not have been made.”

Nonetheless, Tectoy’s efforts in getting the game ported to the Master System in 1997—way after the Master System had been removed from the market in most other countries, by the way—are still fairly impressive, especially considering the technical challenges such a port must’ve created. (It’s not the only port out there, either—this unlicensed Korean port of the game, which came out for the functionally similar Game Gear, makes Tectoy’s port look like Citizen Kane.)

Hey, at least Tectoy didn’t make Mortal Kombat III for the Master System. Oh wait—they did.

In the end, the reason Tectoy succeeded with Sega products in Brazil comes down to a strong understanding of the market—which is the fifth-largest for video games. Because Tectoy was a Brazilian manufacturer first, it was able to drum up interest in the console though marketing that didn’t treat Brazil as an afterthought.

“Maybe the reason for our success was based on low cost, high quality, locally manufactured products, plus aggressive marketing and a good knowledge of our end consumer,” Tectoy President Stefano Arnhold told Hardcore Gaming 101. “We did not only sell them a product, we invited them to join Sega Club where they enjoyed a sense of participating in a community [and] received special promotions (discounts for everything from movie tickets to Formula 1 Grand Prix seats).”

But with Sega having not built a new console in more than 15 years, Tectoy has adapted its strategy a bit. Instead of simply making video games, it now makes DVD players, Android tablets, and even baby monitors. They may not have Microsoft or Nintendo in their corner, but their licensing game is strong—with both Mickey Mouse and Spongebob Squarepants giving their DVD players a little extra snazz.

Perhaps more international companies should partner with local firms that actually understand the market. They might be surprised.

:format(jpeg)/2018/04/bhviluclioomqmpfezni.gif)

/2018/04/bhviluclioomqmpfezni.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)