Livin' on the Edge

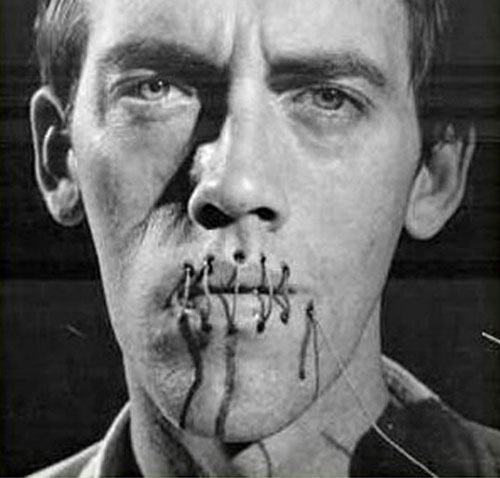

People will always push the edges of creativity when they can—that's why we have Marilyn Manson. Today's issue analyzes art and decency.

"What fans can make happen is what no studio, no channel, no big company would ever support. 'This will not get filmed,' they say. And we can say, 'Yes it will.'"

— Director Uwe Boll, talking to The Hollywood Reporter in 2013 about his effort to get Postal 2 funded via Kickstarter. His goal was to create essentially the most offensive movie ever, going even further than the original 2007 film. Apparently, nobody wanted this vision, because Boll had to cancel his Kickstarter after raising just 5 percent of the $500,000 needed to get the film off the ground.

In defense of ratings systems

Last year,Pitchfork sister site The Dissolve took aim at one of the greatest tools that society has to decide what it's OK with most people seeing: the PG-13 rating.

The rating, as designed by the Motion Picture Association of America, came about because the PG rating proved too ill-equipped for most mainstream movies. The film Gremlins, which included scenes of violence mixed in with its comedic elements, was one particular target of criticism and a key catalyst for the change.

The rating came about to offer something of a middle ground between kiddie movies (G or PG films) and films with mature themes (R ratings). But in effect, the site argues, the rating limits the types of creativity that we see in the cinema.

"The most lasting effect of the PG-13 rating seems to be that it’s kept most mainstream pictures clear of the profanity and sexual candor that populates critically acclaimed cable dramas," writes the publication's Chris Klimek. "Is it coincidence that while major studios have never been less inclined to invest in movies that won’t sell toys, or open huge in non-English-speaking countries, the quality of television storytelling is the strongest it’s ever been?"

But on the other hand, it's important to remember that when these systems work correctly, they offer creative freedoms that were otherwise off limits for creators previously. The video game industry, despite its critics, is a great example of this in action. In 1994, the industry adopted a voluntary ratings system that created opportunities for game makers to try more mature themes on for size—a technique that paved the way for film-like experiences like those presented by the Grand Theft Auto series.

Now, granted, these systems aren't perfect—the MPAA's inconsistency and obtuseness, as highlighted by This Film is Not Yet Rated, proves that broad ratings based on differing cultural tastes will never in fact be perfect.

But for all the faults of this system—particularly its permissive approach to violence and conservative approach to sexual content—it nonetheless succeeds at its main goal. It helps build a diversity of creative voices at the box office. Love it or hate it, American Psycho would never see the light of day under the Hays Code.

By creating parameters, we allow risk, one gremlin at a time.

Five shockmeisters who took their acts way too far

- Sunshine Megatron, the unusually named owner of the website T-Shirt Hell, once claimed his online store (which sells T-shirts designed to get a rise out of people) was shutting down, only to reveal that he made the fact up so that he could make more money for himself.

- Artist Carl Michael von Hausswolff decided regular charcoal wasn't good enough for him, so he decided to create a painting using the ashes of Holocaust victims. Ugh.

- Italian film director Ruggero Deodato was trying to make a commentary on media sensationalism with his 1980 horror film Cannibal Holocaust, which as you might guess features cannibalism as a major plot point. Problem is, Deodato did his job too well and he was prosecuted for allegedly murdering his actors—something he disproved by actually bringing said actors to court.

- Getting banned from the radio is nothing. The Anti-Nowhere League, an English hardcore punk band, one-upped the Sex Pistols by creating a song so offensive that the record was confiscated and destroyed under the British Obscene Publications Act. You can hear that song here.

- The Norwegian black metal band Mayhem perhaps bought into its whole Satanism schtick a little too much—before the band had even released its first album, two of its members had died grisly deaths, and a third was sentenced to jail for murder. "We couldn't really buy better publicity," one of the band's members, Necro Butcher, told The Guardian in 2005. "But every time we lost a member we had to find somebody else to replace them and start the whole rehearsing process again. We suffered in that way as a band."

Offended? Maybe you're missing the point

All it took were a few ants to drive the censors crazy.

In 2010, the federally funded National Portrait Gallery found itself targeted for funding cuts after the Smithsonian-run institution hosted a video created by late artist David Wojnarowicz.

Wojnarowicz, one of the most ground-breaking visual artists of the 1980s, once created a short film, "A Fire in My Belly," that at one point showed a crucifix covered by ants. It was a very small part of a much longer video, but it was just the type of thing that makes members of Congress go insane.

The National Portrait Gallery, spooked by the publicity, quickly hid the video from view.

But Wojnarowicz, who died in 1992 of AIDS-related complications, knew how to take on such attacks against his artwork. When he was still alive, he successfully fought the American Family Association in court, after they misrepresented his work in an effort to remove his funding.

Almost by default, the work of Wojnarowicz and similarly controversial artists like Robert Mapplethorpe is worlds apart from the rest of the United States. These pieces of art represent a world outside of mainstream cultural norms, and are often much deeper than single images suggest.

As Holland Carter of The New York Times explains:

That “A Fire in My Belly” is about spirituality, and about AIDS, is beyond doubt. To those caught up in the crisis, the worst years of the epidemic were like an extended Day of the Dead, a time of skulls and candles, corruption with promise of resurrection. Wojnarowicz was profoundly angry at a government that barely acknowledged the epidemic and at political forces that he believed used AIDS, and the art created in response, to demonize homosexuals.

Politicians (with some exceptions) are by default not artists. That's because politics is about decorum and holding standards pat, while the edgiest art is almost always about pushing limits beyond their bounds.

If you put former House Majority Leader Eric Cantor—a leading critic of "A Fire in My Belly"— in a room with David Wojnarowicz circa 1986, there's a good chance that Cantor would have so little in common with him that they wouldn't be able to have a conversation.

That's why Wojnarowicz had to make art, and why that art had to be offensive to traditionalist tastes. Nobody would have noticed if he was painting happy little trees.

It's tough, even in the context of deeper commentary, to defend a game like Hatred. It's designed to press the buttons of the very people who targeted Marilyn Manson around the time of 1999's Columbine shooting.

But if Hatred becomes the next scapegoat for tragedy, the game's creators would be smart to listen to what Manson has to say on the issue of artistry. In June 1999, Manson defended his music in Rolling Stone.

"Sometimes music, movies and books are the only things that let us feel like someone else feels like we do," Manson wrote. "I've always tried to let people know it's OK, or better, if you don't fit into the program. Use your imagination—if some geck from Ohio can become something, why can't anyone else with the willpower and creativity?"

That's not the message that a lot of people got from Manson's music in 1999. But perhaps it's the one that should have prevailed.

:format(jpeg)/2018/11/bpf7i6kvr5wx19wyzgc4--1-.gif)

/2018/11/bpf7i6kvr5wx19wyzgc4--1-.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)