Over-Filtering The Internet

Despite many, many failed attempts to do so, people keep trying to filter the internet. Let’s look at the lens of the current moment through past attempts—including one led by, of all people, a librarian.

“We want to find ways for parents to have an easier time exercising appropriate control over messages … that they feel are not appropriate for their own children.”

— Former Vice President Al Gore, speaking in 1995 about his support of a computer chip designed to block certain kinds of programs in television sets. Gore’s support of the V-Chip, a parental control tool, helped to drive forth the passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, a which included one of the first attempts by a government to block content, the Communications Decency Act of 1996. That law, which barred access to indecent content to children, helped kick off the uptake in web filtering software. But it wasn’t to last. Much of the law was struck down just a few months after it was passed and blocked by the Supreme Court. That’s thanks in no small part to the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Blue Ribbon Campaign, one of the first successful examples of digital activism. (One portion of the CDA that has stood the test of time, Section 230, has given immunity to service providers for the actions undertaken on their platform. But even that’s looking shaky these days.)

/uploads/Coffee_Filter.jpg)

My point of view on all of this: Edgy content always finds a way

Late last year, when I heard about the passage of Australia’s ban on social media for kids under the age of 16, I described it as “kayfabe”—i.e. pretending to take action on a politically valuable issue.

Someone challenged me on the premise, stating they didn’t understand my opposition to it, saying something along the lines of “The idea itself isn’t bad, it’s just not very enforceable.”

Let me be clear: The idea itself is bad, in my estimation. It is one of many examples of a law that exists to make a statement rather than something that truly solves a problem. And I think the decision to include YouTube as part of the ban underlines this especially.

And I get the motivation—it is an effective way to look like you’re doing something as a government. But it is a real slippery slope kind of situation that often introduces a bunch of dangerous stuff along with it.

And the truth is, it often doesn’t work. Kids are smart. They can work around stuff like this—and have, time and time again. (A teenager with a desire to work around a restriction is a hell of a pentester.) But we’re still stuck with all the bad junk that gets dragged in with these seemingly well-intentioned laws.

Taylor Lorenz has been on top of this beat in a big way in recent weeks, writing multiple articles about it in The Guardian and elsewhere. Recently, in her newsletter User Mag, she brought in a trio of researchers—Cynthia Conti-Cook of the Collaborative Research Center for Resilience, ACLU lawyer Rebecca Williams, and activist Pratika Katiyar, also of the ALCU.

(Side note: She brought User Mag to Patreon recently, which, as someone who has a thing against Substack, I appreciate.)

The guest post has many great parts, but I especially think this point about digital ID systems is especially important:

Age verification laws don’t just fail to protect children; the digital ID systems that enforce them fundamentally change how everyone accesses the Internet and will cause real harm.

Once the infrastructures of unique identification are constructed, it won’t only be advertisers profiling and microtargeting customers but states profiling and microtargeting any political opponents or other public enemies-du-jour. That is in addition to chilling free speech, restricting access to vital health and identity resources, disproportionately impacting historically oppressed communities, and forcing users to hand over sensitive biometric or government ID data to unaccountable third parties.

We must stop the harms caused by digital ID and paternalistic laws like age verification. We can resist with daily acts of resistance, organize, legislate real protections, and litigate.

That’s the key thing for me. It always starts with protection mechanisms intended for one audience, but it changes the way every audience uses the internet. It brings in a new class of companies and motivations, and those motivations can be quite dangerous if not correctly managed.

And we have distinct proof of this in the form of the filtering tools and legislative tactics we’ve seen in the past.

Sponsored By TLDR

Want a byte-sized version of Hacker News? Try TLDR’s free daily newsletter.

TLDR covers the most interesting tech, science, and coding news in just 5 minutes.

No sports, politics, or weather.

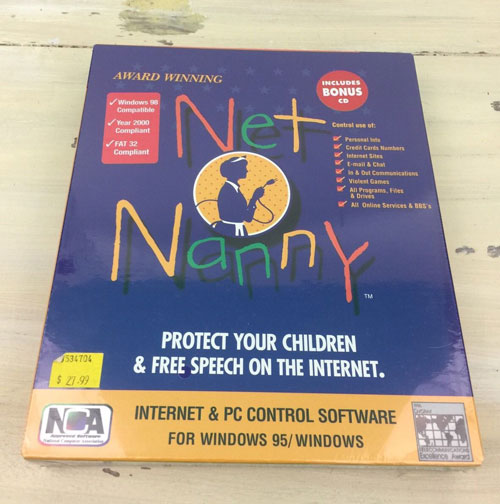

A box for Net Nanny, which (like many of its competitors) played itself up as a free-speech tool. (via eBay)

Five early examples of web filtering tools

- WebSense. Perhaps the best-known filtering program for many years, WebSense came about after its founder, a man named Phil Trubey, saw the potential of the web and realized that filtering products were necessary. “There were a few primitive home-based filtering products on the market when I came up with the concept,” Trubey told The Tampa Tribune in 1998. “But no one had yet introduced a solution that would monitor employees’ internet use.” Yes, while the proxy server-style software is probably best known in schools or libraries, its intended audience was the workplace—something reflected in the fact that the tool has evolved into the modern cybersecurity offering Forcepoint.

- Net Nanny. One of the earliest tools targeted specifically at parents, the content-blocking tool initially took a very aggressive approach to filtering online content by relying on word-based filters, rather than a block list. “Every time ‘What’s your name?’ or a word such as ‘sex’ crosses the screen, Net Nanny shuts the whole thing down and the kid has to get Mom’s help to turn the computer back on,” founder Gordon Ross explained in a 1995 Montreal Gazette article. He added that the goal was to leave the ultimate decision up to the user, rather than the government. “Censorship should come from the computer operator alone, not from the state.” PeaceFire, a now-shuttered digital resource highlighting content-blocking tools, noted that its approach to filtering relied on aggressive keyword use, rather than a long list of blocked sites. Net Nanny, after some ownership changes, is still actively sold today.

- SurfWatch. Dating to the same period as Net Nanny, SurfWatch also took a more aggressive approach to keyword-based blocking rather than relying on a massive list of blocked sites. That became an issue after the tool blocked a page on the White House website featuring information about the Clinton and Gore families. (The problem? The URL was titled couples.html.) The company, however, was better than others when it came to hearing out criticism from groups such as the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, leading the group to stop blocking sites on the basis of sexual orientation. The software may have played a role in the striking down of the Communications Decency Act, as the company made the case in federal court that its software was a more reasonable approach than an overarching law.

- CyberSitter. This platform, initially sold by Solid Oak Software, has had a reputation for taking a more conservative approach to what it would block, something it did not shy away from after GLAAD published a 1997 report that called its software “homophobic.” Speaking to ZDNet about the report, Mark Kanter of Solid Oak leaned into the reputation, despite its competitors doing the opposite. “That has driven our sales to some extent—the fact that we have admittedly blocked gay and lesbian sites, that we have blocked NOW,” Kanter explained. The platform had a reputation for aggressiveness—at one point threatening to block every site on PeaceFire’s ISP if it did not shut the site down. The tool is no longer sold.

- Cyber Patrol. Initially facing similar criticism over blocking LGBT content from GLAAD, the maker of this software actually added a GLAAD member to its oversight board in an effort to quell concerns about its platform. The company took a similar approach to blocking hate speech with its tool, teaming with the Anti-Defamation League to create a filter designed to tackle such issues—while forwarding to the ADL’s website. Cyber Patrol, at one point owned by Mattel, now forwards to a company called SafeToNet, which is promoting a phone that purports to make it impossible to access—or more interestingly, take—explicit pictures. (Seems like that might be a tough phone to review.)

2000

The year that a piece of software called cphack was developed by a Swedish programming team. The tool allowed users to get around Cyber Patrol’s encryption to take a look at the full database of blocked sites, as well as to turn off the software. (This was possible with Cyber Patrol, as it was a piece of software installed on the machine, rather than a proxy tool like WebSense was.) Soon after it was developed, Cyber Patrol sued the hosts of the software—including PeaceFire, which frequently found itself at the center of debates around blocking software—who earned legal representation from the American Civil Liberties Union. After a legal battle, the software distributors emerged victorious after the U.S. Copyright Office decided that “reproduction or display of the lists for the purposes of criticizing them could constitute fair use.”

/uploads/6238548941_359e0a90cf_c.jpg)

How online filtering created a new front in the culture wars

While there are plenty of examples of networked technology before the late ’90s—the Free-Net, for one—things started to pick up after the web became a thing. It started appearing in common settings; think schools, cybercafes, offices, and so on. Things had reached scale.

And this created a need for a market for digital filters, which were intended to serve a role not that dissimilar to the V-Chip—that blocked the bad stuff from being accessed online, while allowing most of the good. This sounded good in theory, but ultimately, the filters weren’t very good. And honestly, the “I know it when I see it” approach to indecency and obscenity, as famously defined by Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart in the 1964 case Jacobellis v. Ohio, breaks down online. When new webpages are being produced by the thousands and even millions each day, you can’t possibly see everything, and suddenly, it becomes a matter of grappling with a whole lot of different standards of what’s safe and what’s not.

In other words, it was a First Amendment issue, and a knotty one at that. Installing the V-Chip in TVs? Compared to content filters on the internet, relatively painless—as soon as Al Gore was convinced, it became downright easy to make the case for it. It empowered parents without actually blocking anything for folks who didn’t want to use it. While some broadcasters might have felt frustrated by a decision that could affect their ad revenue, it was easy for folks who weren’t in the target audience to ignore.

But internet filtering software had many more variables. The internet didn’t have a standardized rating system like television or movies. Anyone could create anything on it—and everyone did. Filtering required much more room for edge cases, such as that of the British city of Scunthorpe.

Naturally, this issue becomes a challenge as Net Nanny, WebSense, and so on, filter things with differing sets of standards. That means you’re basically controlling content based on someone else’s opinion of what’s decent and what’s not—as well as how often they choose to update their filters. Something, inevitably, would get through. Kids are smart.

A 1999 editorial in the Quad-City Times really nailed the problem, suggesting that by handing the job to an automated filtering app, rather than an actual person, the software created complex problems that can’t be easily sorted out by algorithm.

“Unfortunately, the software is not very refined,” the editorial board wrote. “By restricting access to sites that mention sex, for example, WebSense blocks access to sites that contain legitimate news stories on such topics as impeachment of the president.”

On the other hand, you could also argue things the other way, as Oregon librarian David Burt successfully did. Burt, concerned with the potential that children would access indecent material at the library, started up a platform called Filtering Facts. The platform used Freedom of Information Act requests filed by both Burt and a team of volunteers to highlight cases where indecent material had been accessed at libraries.

“I want to keep letting people know about the problem,” Burt told The New York Times in a 1999 article that raised his profile significantly.

The stance went against the party line of librarians at the time—that internet access wasn’t dangerous, that the freedom the internet offered was more important. Many chose not to go along with the FOIA requests, noting that existing laws prevented libraries from revealing who accessed certain kinds of information.

/uploads/Screenshot-From-2025-08-26-21-38-33.png)

Burt’s research, which often took aim at traditional bodies such as the American Library Association, found support from the Family Research Council. FRC published his findings in a report titled Dangerous Access, which advocated for legal action to require filtering tools.

“The failure of many libraries to prevent these incidents combined with the demonstrated effectiveness of filtering software supports the appropriateness of legislation to require the use of filters in public libraries,” the report’s introduction stated.

Burt’s work directly helped to drive the passage of a piece of legislation called the Children’s Internet Protection Act, which required libraries and schools to install filters on computers if they wanted access to federal funding. (The latter part being key because it didn’t tie the legislation to censorship, but to funding.)

But his work actually went deeper than simply the report itself—he spoke during Congressional and regulatory hearings, before and after the passage of the law. And when the American Library Association and American Civil Liberties Union sued over the law, the Department of Justice brought him on as a consultant in the ensuing legal battle. He filed too many FOIA requests to simply let the issue go as soon as he published his report.

Dangerous Access, and Burt’s work on it, was directly cited in the Supreme Court’s 2003 decision to uphold the law. The court making its decision from the standpoint that the law did not violate the First Amendment, as the filter could be turned off for adult patrons upon their asking. The librarian who went against the grain ended up changing the law. And so, these filitering tools, some of which promoted their importance as methods to preserve free speech, ultimately ended up damaging it in one of the most important venues for free speech, the library.

It always starts with protection mechanisms intended for one audience, but it changes the way every audience uses the internet. (If it feels like I said that line already, it’s because I did.)

Burt, these days, is a consultant who previously helped Microsoft navigate the choppy waters of compliance—which makes sense, as parental controls are a compliance issue when you break it down.

Internet filtering, love it or hate it, is here to stay.

$30M

The amount that Circle Media Labs raised over two funding rounds. The company, which sold a Disney-branded content filtering device, attempted to take a smart-device approach to the content filtering problem, one that lives near your router. (It reflects the reality that the ground game around filtering is harder when there‘s a dozen computers in your house, rather than one or two.) While Circle didn’t make it, the company Aura has taken ownership of the service and has one of Disney’s highest-paid actors, Robert Downey, Jr., as its spokesperson.

What’s strange about the recent uptick in interest in online protection laws is that, during the 2010s, it was pretty quiet on the legislative front. I think there was a point where it almost felt like this issue had faded into the ether.

I was a little sad to see, as I was looking into a refresh on this topic, that Peacefire, one of the primary repositories for information about internet blocking software, had largely gone offline. In its place, founder Bennett Haselton has put up a statement, published sometime last year, speaking up for the rights of minors to have unfettered internet access. Here’s the intro to what he built:

I (Bennett) ran this site from 1996 to about 2015, fulfilling three purposes: (a) publicizing the types of errors made by Internet blocking software (e.g. frequently blocking gay rights advocacy webpages as “pornography”); (b) providing a network of proxy websites to get around Internet blockers; and (c) making a moral argument for minors’ rights more generally.

The first two goals are mostly obsolete now, since (a) Internet blocking software is far less in the news than it used to be (in 2024 it’s almost quaint to imagine someone being worried about their teenage kid borrowing someone else’s phone to look at a topless woman); and (b) tools like VPNs are a far easier and more popular way to get around Internet blockers today. But the moral case for minors’ rights is still valid, and in fact in the 2020s the arguments have gone mainstream—but, perhaps oddly, mostly in the specific context of LGBTQ youth and their right to privacy.

The rest of this piece makes a strong case that kids under 18 should be able to have more rights, using vaccines as an example. If you want to get vaccinated and your parents are against it, you should have the right to say no, says Haselton.

(Haselton, who I’ve reached out to as I’m curious what he thinks of all the recent laws, remains a highly active political voice in the Seattle area. He’s the kind of guy who shows up at city council meetings and goes to rallies and such. Given that Peacefire was his onramp to activism, and he started when he was actually a teenager, you love to see it.)

As the past six months (I believe) have proven, there was a tendency to get complacent around both blocking tools and blocking policies. While proxies have become a bit old hat, the fact of the matter is that as users, we perhaps have not put as much of a focus on this topic as we should have.

But while we let the cruise control take over, those concerned about the internet’s unfettered access put on the gas. They will always find new angles to tap into, and two of the recent angles have proven surprisingly fruitful: Discussions on smartphone addiction, and concerns about the safety of children.

When these laws get passed, they often have “safety” or “kids” or “children” in them. It’s a hugely effective tactic: When you decide not to support a bill with these terms in the title, it implies you are against these things. That makes you a target for an attack ad or five. (Just ask, and I can’t believe I’m saying this, Nigel Farage.)

The problem is, laws tend to be written with one goal in mind, but ignore the knock-on effects. LGBTQ issues often get tied into these issues. And honestly, when you screw with the internet that kids can access, it often harms the internet that’s accessible to everyone else. This whole issue has thousands of gray areas, but it’s often presented in black-and-white terms.

In this light I go back to Haselton’s closing thoughts on this issue, on the now-shuttered Peacefire:

And so, as people occasionally stumble across this site, let the site’s legacy be: With regard to minors’ rights, individual liberty and privacy should be the default, and an exception should only be made when there is a good reason, and repeating what the rule is, is not a reason. Most restrictions on the “rights” of little kids do pass that test; most restrictions on teenagers (especially older ones) fail that test. There really is no good argument why you shouldn’t be able to go to a library and check out a book without your parents’ permission, if you want to.

The internet is many things, but it is most importantly a place of self-discovery, a way for people to figure out who they really are. Yes, much of it sucks, but some of it is divine. That journey of self-discovery is yours, and nobody else’s.

When the internet is filtered beyond a reasonable level, especially by someone who isn’t raising you, it limits your journey.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal! And back at it in a couple of days.

:format(jpeg)/uploads/tedium120618.gif)

/uploads/tedium120618.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)