The Scrolling Orb

The evolution of the trackball, which is more than an upside-down mouse. It's the Royal Canadian Navy’s greatest gift to modern-day computing. Really.

Today’s GIF comes from a YouTube channel called GoldFromComputers.com, which for some reason promoted a 2010 eBay auction of a Logitech Trackman using an unusually trippy video.

Sponsored by What’s The Big Idea—Your weekly fix of exciting experiments, weird science discoveries, and questions you never thought to ask!

Get inspiring new ideas into your brain cells, and join our community of out of the box thinkers. Inside this weekly newsletter, we’ll cover everything from incredible green energy solutions, puzzling science problems, groundbreaking psychology discoveries, and bizarre ways the world might evolve in the not so distant future.

If you like the New Scientist…

If you’re always thinking of new ideas and want to nurture your creative juices…

Or if you simply like reading cool stuff...

Stay in the loop and join a new movement of backyard inventors.

The 5-pin bowling ball found a second life as the first trackball. (Benjamin J. DeLong/Flickr)

The trackball is older than the mouse, and we can thank the Canadian military for it

So, as it turns out, before the virtual bowling alley borrowed something from the trackball, the inventors of the trackball borrowed something from the actual bowling alley—specifically, the Canadian variation of it, called 5-pin bowling.

Unlike the giant hulking rocks that tend to get thrown in American bowling alleys, 5-pin relies on a ball slightly less than 5 inches in diameter—larger than a skee-ball (which is 3 inches in diameter) and roughly the size of the ball used in duckpin bowling, but using five pins, instead of 10 (hence the name).

Clearly, this is a fairly novel point about an object that has inspired a lot of other devices that have come since—and its one that hints at its initial creation in the early 1950s. The device is Canadian through and through, a project formulated at the behest of the Royal Canadian Navy by Ferranti Canada, as part of a much larger project—a military information system called Digital Automated Tracking and Resolving, or DATAR.

DATAR represented perhaps one of the most ambitious projects of the budding Canadian computer industry at the time, a sophisticated machine that allowed ships to transfer radar and sonar data with one another. The machine was conceived by Navy researcher Jim Belyea, who took advantage of a failed meeting between Ferranti and the Navy to pitch his ambitious idea. According to a 1994 IEEE article, Ferranti was extremely impressed by Belyea’s vision.

“It seemed to our group that what [Belyea] had in mind was very much the proper thing to be doing,” the company’s Kenyon Taylor said. “It was a first step in push-button warfare. Lt. Belyea was thinking 15 years ahead of his time and Sir Vincent de Ferranti and the rest of our party were well in tune with him.”

DATAR, considering both what it was and how early it was in computer history, was a very complex piece of work, having to integrate a number of cutting-edge technologies into a single machine. According to Georgi Dalakov’s History of Computers website, the resulting prototype used 30,000 vacuum tubes, and with its drum memory system, it could store 500 objects.

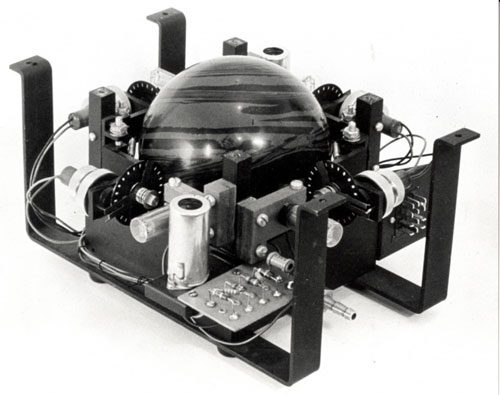

An early prototype of the first trackball. Note the stripes on the ball. (via the Engineering Technology and History Wiki)

That machine included a radar screen, and that screen just happened to be controlled by a 5-pin bowling ball. Invented by Tom Cranston and Fred Longstaff and relying an air-bearings system formulated by Taylor, the system worked like this: An operator, using a terminal, would scan over an area using the trackball to target the correct area on the radar screen, and they would hit a trigger to store the information on the screen, and that information would get transferred to other ships.

As it turned out, the idea, ambitious as it was, was eventually thrown out in favor of a system used by the U.S. military—not because it wasn’t great (it was), but because the Canadian Navy wanted to be able to communicate using the same system as a close ally. The U.S. Navy’s solution, Naval Tactical Data System, could also input data automatically that DATAR required manual input for. (Also, it turned out that putting thousands of vacuum tubes on a ship is a bit of a technical challenge.)

It wasn’t a complete loss. Ferranti reused much of the technology for its mainframes, including those it made after its merger with Packard Electric in 1958. The company was ahead of its time in other ways—the FP-6000 computer, built from the remains of DATAR, supported multitasking.

But the trackball, strangely enough, turned out to be the greatest legacy of one of Canada’s first major computing projects. The only downside, really, was the fact that, because DATAR was a secret government project, Ferranti couldn’t patent its invention.

Them’s the breaks, apparently.

“Think about the state of play in the computer world in 1952. There were only a handful of operating computers in the world. Almost all were unreliable. There was no common software language... pulse rates were only 50-100kHz. The idea of using a ball to control a cursor which could intervene and change program execution was a million miles ahead.”

— Tom Cranston, the co-inventor of the trackball, talking to the defunct UK-based magazine Personal Computer World in 2001 about the significance of his invention at the time. While ball-based devices had been in use previously, the innovation of what they produced, per the magazine, was that it directly impacted what showed up on a computer screen. Cranston, who died in 2009, added that the device was a full generation ahead of what other inventors were doing during the period. In fact, the trackball came a full 16 years before the German company Telefunken invented a ball-based mouse in 1968, and a decade before Douglas Engelbart created his variation, which didn’t rely on a ball.

Air-Traffic Controller 1st Class Justin S. Brown, shown in 2012 tracking incoming aircraft from the carrier air traffic control center aboard the aircraft carrier USS George H.W. Bush. Brown is using a trackball. (Wikimedia Commons)

How the “slew ball” helped define the job of the air traffic controller

Over the years, the trackball found its way to the consumer market and the broader public. But before that happened, it gained an important niche use in an industry that was coming into its own along with the broader airline industry—the air traffic control field.

ATC workers need to be able to track what’s happening in the sky to ensure a flight going in the air has a clear path, and that requires 360 degrees of movement, specifically the ability to change angles on the fly. The concept of “slewing,” or rotating around an axis—usually the z axis, in the case of aircraft—was as a result an important one, and one that the trackball made easy to control.

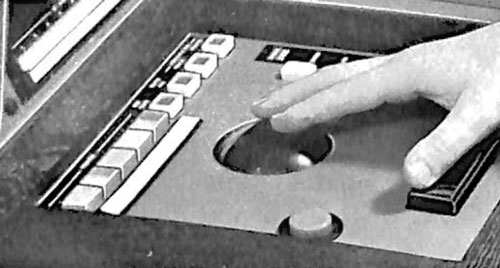

An example of a “slew ball” from the 1960s. (via the IFATCA Journal of Air Traffic Control)

And as a result, it wasn’t called the trackball in the world of air traffic control—it was called a “slew ball,” a term used as early as 1967 in the publication by the International Federation of Air Traffic Controllers’ Associations. The word “trackball” didn’t come into common use until the 1970s and 1980s.

A 1981 Philadelphia Inquirer article, published around the time Ronald Reagan infamously fired thousands of striking air traffic controller union employees, explains how the use of the “slew ball” played out in action as a plane got close to the airport.

Your plane is one of 70 to 100 little blips moving across that screen. The controller punches the right code into a lighted green and orange key-board, and a number appears by the blip that is your plane.

Once a controller has received the handoff, the computer automatically enters his code letter beside that number, and he begins to spin his “slew ball.”

The slew ball is a smooth glass ball, identical to those on the electronic football games in a penny arcades, and he spins it with his palm. It moves a marker across the radar screen, and he lines it up over your plane’s blip.

Then he “zaps” you.

He pushes a button to “interrogate the target.” The altitude of your plane flashes onto the screen, and the computers in your plane’s cock-pit lock on to those in the radar room.

In many ways, the slew ball was the one thing separating humans from a mission-critical application, and it worked effectively in that role.

In fact, when the computer mouse started becoming common and air traffic controllers were getting trained to use it, there was at least some evidence of resistance, because trackballs were already in wide use.

“The main interactive tool was the mouse, but many subjects were not familiar with the use of the mouse. For those unfamiliar with the mouse, the training was too short,” a passage from a 1989 report by NASA’s Ames Research Center stated. “Controllers commented on their unfamiliarity with the mouse, and their preference for the trackball currently in use in the ATC system.”

It’s a fascinating situation that has likely played out in lots of other ways in the past—a niche piece of technology takes over a single sector to the point where its more mainstream alternative feels foreign when it’s finally introduced.

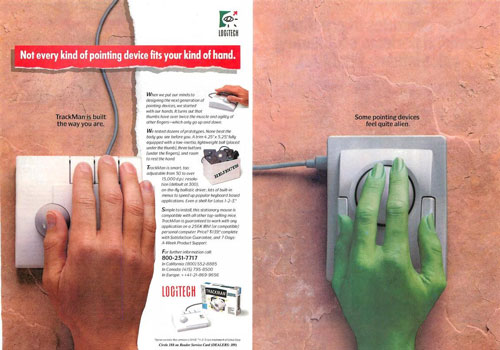

An early ad for Logitech’s Trackman. (via Xah Keyboard Guide)

Five key points in the mainstream evolution of the trackball

- A 1973 article in the Shenandoah, Pennsylvania Evening Herald is the earliest reference to a trackball I can find in a U.S. newspaper. In this case, the reporter was more focused on the fact that a TV monitor was a key element of the computer used to control an electrical system.

- Arcade machines started to include built-in trackballs in the 1970s, with the real turning point for the input devices, decades before Golden Tee, being 1978’s Atari Football tabletop arcade game, which looked more like a quarterback’s play chart than Madden. Atari would soon follow this game up with two trackball-driven arcade classics—Missile Command and Centipede.

- The Atari 5200, while a commercial failure that was taken off the market less than two years after its 1982 release, featured a trackball controller that was quite good—especially compared to the 5200 joystick, which infamously had a stick that didn’t center. A clip on the YouTube channel Wired-Up Retro explains that, unlike many other trackballs built for similar consoles, it uses an analog control, which made it flow more smoothly on games like Centipede and Missile Command.

- On the home computer front, trackballs had been around in one form or another since 1983 or so, with arcade-quality trackballs showing up for computers along with video game consoles. But the real turning point came in 1989, when the Swiss accessories manufacturer Logitech created the ergonomically minded Trackman, which had buttons on one side of the device and the trackball on the other. Though it wasn’t entirely unique to the market, the device became one of that company’s enduring hits.

- The 1989 release of the Apple Macintosh Portable represented one of the earliest attempts to integrate a cursor into a portable computer, and since a mouse took up space, a trackball turned out to be the preferred option. The computer wasn’t very good, of course, but the trackball stuck around in many of Apple’s early Powerbook models. (The trackpad would replace it starting in the late ’90s.)

1992

The year that Nintendo released Kirby’s Dream Land, the Game Boy game that was the first in the popular Kirby series. Earlier this year, the game’s developer, Masahiro Sakurai, revealed that he programmed this game using a Famicom-based visual programming tool that had no physical keyboard—just an onscreen keyboard that could be controlled with a trackball. According to a translation of his blog post on Source Gaming, Sakurai, who was new to the industry at the time, didn’t question the process and successfully created the game using a limited tool.

Here’s a question to ponder from a historic perspective: Is the trackball just a glorified mouse? Or is it a distinctive device with its own benefits, design approach, and use cases?

Certainly, it gets used in similar ways to a mouse or trackpad, and it certainly inspires some strong partisans, like this YouTuber. But it also has a history that both predates competing input devices and gives it a cultural context separate from its upside-down friend. (No bowling balls were used in the creation of the mouse.)

A Centipede arcade cabinet. The trackball in this machine is roughly the size of a regulation pool ball. (jan zeschky/Flickr)

Even if when you break it down, the functionality is quite similar—though, as trackball partisans will tell you, pinpoint control is far easier with a marble-sized lump of plastic. And just as Mario Paint wouldn’t be the same without a mouse, Centipede is just better with a trackball.

Admittedly, it’s worth considering that, yes, the trackball isn’t as popular as either its rodent cousin or the trackpad, which quickly usurped the trackball’s role as a laptop mainstay due largely to the smaller number of moving parts. And the partisan arguments around trackballs, once a defining debate of the Windows era, now seem a bit old-hat considering that touchscreens have taken over so much of our computing experience.

But while the trackball has never been the choice of the masses, it’s never completely faded, either. Last month, in fact, Logitech is still releasing models of its Ergo trackball.

Perhaps the trackball isn’t for everyone—but maybe it’s for you. Maybe you have something in common with an air traffic controller from the ’80s.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal!

And thanks again to What’s the Big Idea for sponsoring—be sure to subscribe!

:format(jpeg)/2017/10/tedium101217.gif)

/2017/10/tedium101217.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)