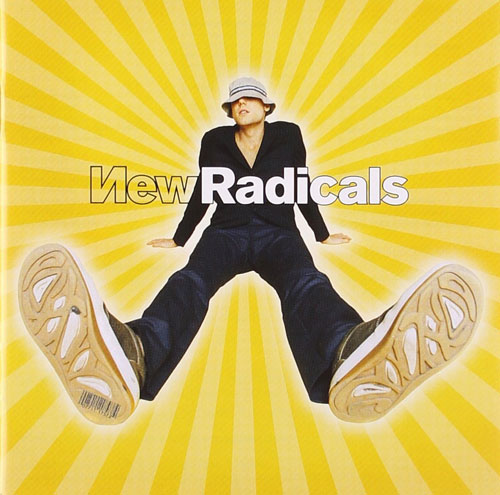

Maybe You’ve Been Brainwashed Too

Pondering “You Get What You Give,” the one-hit wonder recorded by a guy smart enough to realize that it would be a one-hit wonder. It’s a survival story.

Sponsored By TLDR

Want a byte-sized version of Hacker News? Try TLDR’s free daily newsletter.

TLDR covers the most interesting tech, science, and coding news in just 5 minutes.

No sports, politics, or weather.

Everclear, fully embracing its status as a band playing the hits. (Harmony Gruber/Flickr)

The tragically unhip status of a ’90s alt-rocker

The second life of a late-’90s alternative rock musician, especially a lead singer, is usually not particularly glamorous. While some radio staples of the era (Pearl Jam, Beck, Bjork, Gwen Stefani, Dave Matthews, Rob Thomas, Weezer, Ben Folds, Dave Grohl) have transcended this status to become elder statesmen and stateswomen of popular music, many rock-radio hit-makers of the era have become straight-up defined by their period of momentary glory. Decades beyond their initial success and predating the nurturing nature of social media to keep fanbases hooked, many have been relegated to oldies tours.

Everclear, one of the better bands of this specific era, is a key example of this. The act hasn’t had a hit since the early 2000s, and Art Alexakis is the only tie to the legacy era. Despite this, it has maintained a touring presence, leaning hard into the idea of alt-rock being an oldies game. In 2012, Alexakis launched the Summerland Tour, a festival that gave still-active rock acts from the late ’90s access to rock venues around the country. Among Summerland’s alums are a number of bands known primarily for one song: Marcy Playground, Spacehog, Sponge (OK, I’ll give ’em two), Eve 6 (ditto), and Local H.

While that specific tour hasn’t taken place since 2021, the spirit of the alt-rock oldies circuit has picked up in recent years, with many of these same bands on the bill.

Drama has not been unknown for some of these bands, particularly the well-documented legal battles of Live. For example, the lead singer of Marcy Playground had a spotlight put on his personal life last year after his son recorded a single called “Child Support,” the video for which includes home movies of a happy childhood that wasn’t his son’s.

Part of the reason so many bands became known for a single song, as I’ve noted in the past, is because the music industry (at least on the rock side) was very radio-driven in the late ’90s. That led to unhealthy outcomes for major label bands, who couldn’t maintain a long-term career unless they hit a certain threshold of critical acclaim or musical success. If you weren’t Beck or Radiohead or Bush or Stone Temple Pilots, your major label deal might be in jeopardy.

Bands that built a less-showy cult following were often, ironically, better off over the long haul than overnight success stories.

One-hit wonders that managed to stick it out into the present day, such as Nada Surf and former Refreshments lead singer Roger Clyne, survived because they got off their major labels and went independent, where the odds of a steady career of working in music were just a bit better.

(This dynamic is starting to change, admittedly. In particular, Max Collins of Eve 6 has shown that it’s possible for a band with a couple alt-rock hits to get off the oldies circuit and build a fresh road for yourself through a clever social media strategy.)

Sometimes, you have to embrace your status as a band that plays oldies tours. (Harmony Gruber/Flickr)

Even bands with sizable late-’90s success, like two-time Summerland alums Sugar Ray, have found their second acts somewhat wanting. That band’s singer, Mark McGrath, has parlayed his TRL-era fame into a lengthy career as a media personality, complete with a Celebrity Big Brother appearance. He has also become the lead singer of Royal Machines, an all-star cover band built from the roots of an earlier all-star cover band, Camp Freddy.

Really, the best gig one can have as a late-career alternative rocker, beyond a robust touring business, is taking a role behind the scenes. Semisonic lead singer Dan Wilson didn’t win his well-deserved Grammy for “Closing Time,” the greatest song ever written about childbirth, but his mantle has gained plenty of hardware nonetheless, thanks to his significant songwriting and production skills. Among other awards, Wilson has earned Grammys for working with the Dixie Chicks—he cowrote “Not Ready to Make Nice”—and Adele. Wilson produced “Someone Like You,” the closing track on 21, the best-selling album of the past decade, as well as one of Adele’s biggest hits. That’s no small feat.

(Semisonic’s drummer, Jacob Slichter, wrote a great book about being in the music industry that feels relevant to this conversation.)

And Better Than Ezra lead singer Kevin Griffin, whose band should have been more famous than it actually was (“At the Stars” is a good song, fight me), has become an active songwriter himself; remember the Howie Day song “Collide”? He co-wrote that, along with numerous songs for the Barenaked Ladies, who themselves have leaned hard into the oldies circuit of late, touring with a reformed Hootie & The Blowfish, among others.

Call it the Rob Thomas template: While Matchbox Twenty had a lot of staying power, a big reason for that staying power came from Thomas’ songwriting collaborations with other artists. Most famously, of course, he co-wrote and sang “Smooth” with Santana, ensuring that every bar in every city, at some point during the day, would have someone saying, “Man, it’s a hot one …” on the loudspeaker. Score the right hit, and you’re set for life.

Given all that, Gregg Alexander was a genius for breaking up New Radicals when he did. What seemed like a very rock-star thing to do—quit a band before it had a chance to even shine—was actually quite brilliant.

Here’s why.

“There was a long time where no matter what I did, I could be absolutely certain that the first paragraph would be a snide dismissal of ‘Flagpole Sitta’ with a little twist at the end of ‘But I like it okay.’ No one could just admit that they liked it or say they hated it. It was always couched in dismissal. I happened to be hypersensitive to that. Which is a stupid thing to be, but I am nonetheless.”

— Sean Nelson, the lead singer of Harvey Danger, discussing the odd status of his band’s biggest hit in his life during a 2013 interview. Before leaving Seattle in 2018, Nelson spent more than two decades as an editor and contributor at the Seattle alt-weekly The Stranger, while periodically performing and touring with various well-known Northwest bands, such as The Decemberists, The Long Winters, and Death Cab For Cutie. (Harvey Danger broke up in 2009, and Nelson’s 2013 interview celebrated the release of a solo album.) Nelson’s long-term gig as a journalist with one foot in the music industry has periodically created unusual situations, such as in 2015 when he wrote a news story about Critical Mass activists going after a Zipcar driver while “Flagpole Sitta” was playing on a speaker attached to one of the cyclists’ bikes. “It’s enough to make you take public transportation,” he wrote.

Wake up kids, we’ve got the dreamer’s disease.

Why New Radicals’ breakup was the best thing that could have ever happened to Gregg Alexander

New Radicals may be the only band broken up by press release.

It was a damn good press release, too, courtesy of Gregg Alexander himself. He wrote of his desire to move back into production work, to focus on being in the studio and songwriting. He even knew the perfect person to work with: Danielle Brisebois, the former child star who added a late-season dynamic to All In the Family and had resurfaced in his band. (The album was never released, but Brisebois remains a close collaborator with Alexander.)

He also wrote about being tired of the hustle that came with a band on the brink of long-term success. While he had a hit single, the odds of scoring a second one weren’t great. He knew what was coming. He got ahead of it before it defined his career and life.

From the press release, here’s what Alexander had to say:

It was an experience playing the artist, but I accomplished all of my goals with this record, and I’m ready to move on and make the next step in my career. I’ve been writing songs for and working with artists as varied as R&B acts to Belinda Carlisle intermittently for the last nine years, and I’m looking forward to starting the day-to-day creative process of building a successful production company. I view myself much the same as a just getting started Babyface or Matthew Wilder (No Doubt producer), who dabbled in performing, but whose real calling was being a producer.

The band’s album was well-reviewed and their single well-regarded, but Alexander probably knew that there was likely more potential for him to have a decent career if he moved behind the scenes. Someone better suited to the “hanging and schmoozing” of being a pop star, as he described it, could do all that.

As he noted, he had already found success as a composer. After his first two albums as a solo artist, Michigan Rain and Intoxifornication, tanked, that was how he made his money before forming New Radicals.

(By the way, Gregg Alexander’s first attempt at stardom didn’t receive much critical acclaim. A Chicago Tribune review of Intoxifornication said this of his appeal: “The ‘Beverly Hills, 90210’ version of Prince is here, complete with gorgeous face, guitar, and songs filled with sexual play-by-plays.”)

But the experience of creating the two albums, which had a more melancholy sound than his later band, was nonetheless important. The producer on those two albums, a guy named Rick Nowels, became key to Alexander’s later success as a songwriter. You may not know Nowels by name, but you’ve heard his resume on the radio. Among the songs he’s credited on: Belinda Carlisle’s “Heaven Is a Place on Earth,” Dido’s “White Flag,” John Legend’s “Green Light,” and Lana Del Rey’s “Summertime Sadness.” He co-wrote the title track on Celine Dion’s breakthrough Falling Into You, three tracks on Madonna’s Ray of Light, and worked on solo albums for most of the Spice Girls. In recent years, he’s worked closely with Del Rey in particular. Another frequent collaborator? Gregg Alexander.

Nowels co-wrote “You Get What You Give” with Alexander, and after the New Radical went behind the scenes, the songwriters kept up the partnership, most famously on “The Game of Love,” a Santana collaboration with Michelle Branch. That song became the “Smooth” of 2002, and later won a Grammy.

Here’s a fun fact about the tune: The song was originally demoed with Alexander performing the vocals, but producer Clive Davis decided a female vocalist would be a better choice. It took them a few tries to find the right one: First, Tina Turner was brought on board, but the semi-retired soul icon didn’t want to do the video; then Macy Gray was brought in, but the vocals weren’t to Davis’ liking. Finally, Michelle Branch was pulled in, resulting in one of the biggest hits of the early 2000s.

(Santana was partial to Turner’s version, which was eventually released on a compilation disc.)

That means there’s a version of the song with Alexander’s vocals on it. Wondering what that would sound like? Here you go.

Most of the songs he’s worked on, however, haven’t gotten as much notice—something that was largely by design, as Alexander used pseudonyms such as “Alex Ander” (as he did on “The Game of Love”) and also collaborated with artists with relatively small American profiles, such as Boyzone’s Ronan Keating, for whom he’s co-produced at least four albums.

Alexander has often taken breaks from music in favor of pursuits like activism. He’s largely avoided interviews, but resurfaced in The Hollywood Reporter in 2014. The occasion? John Carney, the musician-turned-director best known for Once, brought Alexander in to work on his film Begin Again. That film, a music industry-themed romantic comedy, starred Keira Knightley, Mark Ruffalo, and Maroon 5’s Adam Levine. (Levine, side note, knows a thing or two about the music industry circa 1998; ask him about Kara’s Flowers sometime.)

Alexander noted that the film’s story reminded him of his own time in the music industry, and signed onto the project, writing most of its songs with many of his frequent collaborators, including Brisebois.

One of the songs he wrote, intended as the film’s centerpiece, was “Lost Stars,” which was nominated for an Oscar for Best Song—hence why Alexander started appearing out in public again.

“‘Lost Stars,’ more than any other song in the film, was the one where you wanted to get out a philosophy that Keira’s character would sing but Adam would relate to, and something that would also touch a contemporary audience,” Alexander told Billboard as he made the awards-season rounds. “At the end of the film, it’s a young audience watching this song that really has a lot of pathos and pain in it, but yet people are doing this.”

The thing is, Alexander never stopped being a great performer—as a video from 2014 of the songwriter singing “Lost Stars” in the studio proves. But he doesn’t need to lean on that to be successful in music, and that gives him the space to surface only when he wants to.

Recently, he was given a reason to do so.

Doug Emhoff hits the stage at the Democratic National Convention to “You Get What You Give.” Yes, that’s where the story behind this song has gone.

How “You Get What You Give” turned into an emotional anthem for the executive branch

In recent years, “You Get What You Give” has increasingly become associated with the top tiers of the Democratic Party. And it’s for a tearjerker of a reason. In his 2017 book about the loss of his son Beau, Promise Me, Dad: A Year of Hope, Hardship, and Purpose, Joe Biden wrote of how Beau, amid his frequent chemotherapy treatments, would constantly play the song so much that the current president “thought it was his theme song.”

“In retrospect, I think Beau played that song during our mornings together—not for him, but for me,” Biden wrote. “To remember to not give up or let sadness consume me, consume us.”

When Biden was running for president three years later, the song stuck around as an emotional discussion point to highlight Biden’s compassion towards family. Alexander noticed—enough so that the band reunited to play the song for Biden’s inauguration.

It turns out that Biden wasn’t the only member of the 2020 campaign that had an affinity for the works of Gregg Alexander. Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff reportedly started using the song on his own accord ahead of speeches starting in 2020, not because of the Beau story, but because he liked the song. The Second Gentleman has continued to embrace the song, and Alexander and Emhoff met during the Democratic National Convention this past week, where Emhoff went on stage to the sound of Alexander’s voice.

That was enough to get Alexander to write a lengthy open letter to Emhoff, which was published in Billboard recently—and mentioned that an adaptation of Begin Again is about to premiere on Broadway, complete with additional music from the guy from Train.

That’s not even the only iron in the New Radicals fire, it turns out. Earlier this year, one of Alexander’s early-2000s collaborations with artists across the pond, Sophie Ellis-Bextor’s “Murder on the Dancefloor,” became a viral hit, “Running Up That Hill”-style, after it was featured in the Emerald Fennell film Saltburn. Despite Ellis-Bextor’s name on the tin, it is technically a New Radicals song, as it was an unfinished holdover from Maybe You’ve Been Brainwashed Too that Alexander and Ellis-Bextor polished up for release.

Last week, Alexander saw a way to both highlight his recent successes and show his support to the political party that has embraced his song. From the letter:

I’m writing this letter to you to send out an S.O.S. to all the artists and music people across America that the clock is truly ticking for us to save our democracy.

The time is clearly NOW for all to jump in and use whatever influence for the greater good and endorse the candidate who doesn’t “weirdly” (love that Coach Walz!) advocate taking away women’s rights and everyone’s freedoms. Or brags he’ll cancel America’s Presidential election in 2028!?

In that spirit, if we can talk music a moment, we are releasing the first New Radicals music in 25 years to rally the cause of democracy and encourage all artists to get out the vote. This isn’t some “comeback”; this is us doing our small part to support the fight for freedom!

Hearing these songs done by a band that only exists in 2024 by choice of the artist is a bit of a trip.

Even if you hate John Carney’s sappy music movies (what kind of monster are you?), there’s a lot to appreciate about “Lost Stars,” which is a song that doesn’t quit, less a verse-chorus-verse setup as a buildup-more-buildup–even-more-buildup-payoff setup. And yes, Alexander sounds nearly as good as Adam Levine did. Would Alexander have written a New Radicals song like this? Would his profile match Levine’s? Maybe, maybe not. The music industry, even today, is still built on sheer chance, not just talent.

“Murder on the Dancefloor,” meanwhile, is the more interesting of the two songs, as it introduces us to a world where, if New Radicals continued, this might have been the lead-off single on an imagined second album. Its Euro-disco sound fits neatly into the era it was created, even if Ellis-Bextor feels like a more natural performer of the final product.

We probably aren’t getting a second album from the ultimate one-hit wonders. But it’s nice to know that this band is getting a second life.

On its merits, “You Get What You Give” was one of the best pop songs of its era, classically soulful, evoking the best of ’60s soul and the best parts of a John Hughes film soundtrack.

But at the time of its release, it became a target for controversy due to a ticking time bomb Alexander dropped at the end of the song. The lyrics did two things: First, they casually highlighted numerous incongruent political issues, calling health insurance a rip-off and big bankers a threat, hinting at the overblown status of the looming Y2K bug, and questioning the ethics of cloning animals. The lyrics then slammed a bunch of pop stars. You know the lyrics, but let me publish them here for posterity:

Fashion shoots with Beck and Hanson

Courtney Love and Marilyn Manson

You’re all fakes, run to your mansions

Come around, we’ll kick your ass in

It was a test. Alexander wanted to see if the major label push he knew the record would get would lead the media to pay attention to his willingness to talk about serious political issues. Or instead, would they focus on his willingness to fight a trio of generally wholesome teenage brothers from Tulsa, Oklahoma? We all know what happened, and it likely drove the success of the song because it gave people something to talk about.

Speaking to The Hollywood Reporter in 2014, though, it was clear Alexander was still bummed at the results of that test.

“But to put them next to each other, and then to notice that everybody focused on the so-called ‘celebrity-bashing’ lyric instead of this lyric that was talking about the powers-that-be that are holding everybody down … That was something that I was kind of disillusioned by,” he told the magazine’s Scott Feinberg.

Love or hate the song, or the controversy, it simply highlighted Alexander’s savvy as a creator.

The music industry was making money hand-over-fist at the tail end of 1998. But the artists making the music didn’t necessarily share in that success. Naturally, that state of affairs was soon to get disrupted. Soon enough, the power of your following mattered more than your label’s marketing budget. The old calculus of aggressively promoting a song and then ditching a band after their big hit was off the charts finally looked like bad business.

New Radicals caught on at a time when they could play that game, but Gregg Alexander was smart enough to know that it was better to jump off before the industry ate him alive, and instead focus on his creative output.

It sure beats the oldies circuit.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal! And if you want to support our little slice of Tedium, throw us a little nudge on Ko-Fi.

:format(jpeg)/2018/10/tedium100918.gif)

/2018/10/tedium100918.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)