Fall Of Voodoo

In a few short years, the graphics card company 3Dfx Interactive provided a polygon-laden shock to the PC world—then fell apart, fast. What happened?

Today's GIF is a sample of what Quake looked like on a Voodoo card back in the day. Watch the full clip here.

“It was painful to watch 3Dfx slip from the archetypical kick-ass technology startup to where they wound up. I think I would have been happiest to have the PC market divided up between three strong players that all had their act together, but at this point, I'm not too unhappy with the market simplification resulting from 3Dfx exiting.”

— John Carmack, the longtime id Software programming guru who currently serves as Oculus VR’s Chief Technical Officer, discussing the shutdown of 3Dfx in 2000. (He made these comments, somewhat ironically, to Voodoo Extreme, a 3Dfx enthusiast site.) Carmack served on the graphics card maker’s technical advisory board and expressed frustration with the slow pace of the company’s Rampage project.

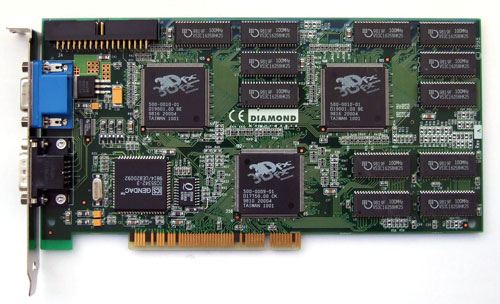

A Voodoo2 graphics add-on card, as produced by Diamond. In particular, Diamond saw much success working with 3Dfx. (Wikimedia Commons)

The corporate failures and missed opportunities that set the stage for 3Dfx

Around the time that 3Dfx and other 3D graphics card makers were just getting their footing in the market, the computer maker Silicon Graphics was helping to supply Nintendo with much of the 3D technology it was using in its Nintendo 64.

SGI had much of the technology to drive the industry forward, but the company was built around ultra-high-end supercomputers, and that left standard PCs out of the equation.

But the thing was, there was a market on the PC—potentially, a big one, one that was only being hinted at by the early success of shareware games like Doom. SGI, which was selling $100,000 development kits to aspiring N64 publishers, was not the right vessel to reach what promised to become a sizable market. Put another way, they were the Wang Computers of 3D graphics—a company riding the prior generation’s horse.

But there were signs something important was coming. In 1995, Microsoft purchased a startup called RenderMorphics, whose technology became the basis of Direct3D, which became a fundamental standard for 3D games on the PC. Around that same time, id Software was knee-deep in development on Quake, which had an engine built from the ground up to generate 3D worlds from even modestly fast Pentium processors. While the earlier Doom is arguably more influential overall, Quake would prove to be something of a killer app, helping to drive interest in 3D graphics cards.

While SGI wasn’t well-suited to take advantage of the market shift toward commodity graphics, its alumni were. And in 1994, three of those alumni—Scott Sellers, Ross Smith, and Gary Tarolli—launched 3Dfx.

The path that got them to the point of creating a startup was a bit messy. A quite in-depth oral history done by the Computer History Museum, which I’ll reference a lot here, notes that a prior offshoot of SGI, Pellucid, eyed the idea of making 3D graphics cards for PCs, and the firm was acquired by Media Vision, a firm known for selling competitors to the Sound Blaster. Media Vision, which often bundled its multimedia tools into a single kit, would have been a fit for what the trio was trying to do.

“So it made a lot of sense to actually build this 3D product as part of Media Vision,” Sellers recalled. “Except there was just one minor problem, which was Media Vision was run by crooks.”

That company soon splintered after reports of financial malfeasance, and that led the trio into the arms of venture capitalist Gordon Campbell, who funded what became 3Dfx.

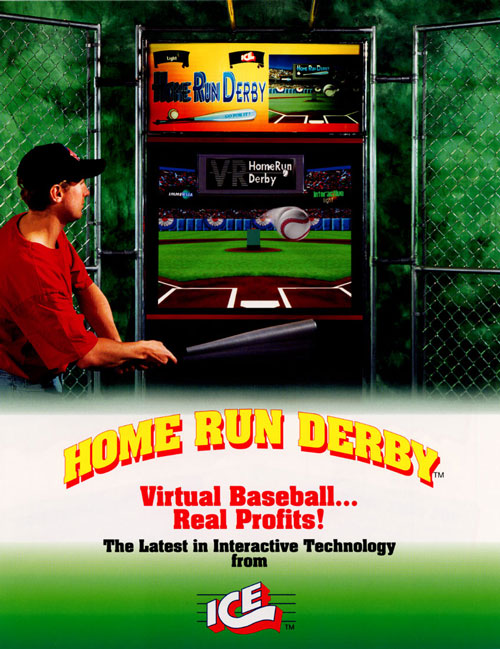

Home Run Derby, the first arcade game to use a 3Dfx chip. (The Arcade Flyer Archive)

Initially, 3Dfx and its Voodoo technology were focused intently on the arcades, and the company’s big debut came at the 1996 edition of the Electronic Entertainment Expo. The first game that used its GPU technology, believe it or not, was a virtual batter’s box called Home Run Derby. The game was massive and players used a baseball bat to play.

“To play, a batter enters a batting cage and stands at home plate in front of a big screen monitor, awaiting a pitch. A 3-D ball is then hurled towards the batter,” an early press release explained of the game. “As it nears home plate, the batter swings. Interactive Light s proprietary infrared sensors instantly measure the batter's timing to determine speed, angle and orientation. These measurements determine the direction of the ball, and whether or not it will be a home run. The ‘camera’ follows the ball into the field on a hit or into the crowd on a home run.”

Sure, the arcades were a great place to introduce 3D graphics to the world. But the arcade industry was a struggling beast by that point. And soon, a much larger opening emerged—and 3Dfx was just the company to take advantage of it.

$30

The cost of RAM, per megabyte, at the beginning of 1996, according to a detailed price comparison of Byte magazine ads by retired computer science professor John C. McCallum. (You might remember his analysis from my piece about the RAM shortage of 1988.) In the two years prior, the price per megabyte actually jumped significantly, but by the end of 1996, the price per megabyte had fallen to just $5.25 per meg. That sharp drop, especially for the extended data output (EDO) RAM preferred at the time, helped make 3D graphics cards much cheaper than they would have been otherwise—and effectively made the products accessible to consumers.

A comparison between Quake in VGA mode versus with a 3Dfx chip. (Mark D. Rejhon)

Four reasons 3Dfx’s Voodoo Graphics took the PC world by storm

- 3Dfx had its own API and successfully pitched it to developers. According to the Computer History Museum’s oral history, company co-founder Ross Smith noted that the company was able to take advantage of the fact that most games were being developed in DOS at the time of its release to create its own API, GLide, and sell it to game developers. “And that was very radical for a graphics company to be doing that,” Smith recalled. “Because normally, you would just use whatever API Microsoft published or whatever. And you'd build this hardware and hope for the best. We couldn't do that, because there were no APIs.” This meant all the big games that supported 3D graphics backed 3Dfx.

- It won over Quake—and John Carmack. Quake was considered 3Dfx’s initial killer app, per Sellers, but 3Dfx played a direct role in making that win happen. The company took advantage of the fact that id Software made available the ability to extend the game’s rendering capabilities, then showed them to Carmack, who built the Quake engine. “And that was a huge step for us. Because once he saw it, then his mind just started cranking,” Sellers noted in the oral history. “And he very quickly went from being kind of a software rendering purist, to one saying, hey, I don't need to do all this stuff anymore. I can take advantage of the hardware.” The result of winning over Carmack was an instant surge in the company’s sales—as well as helping to influence the industry as a whole.

- It focused on 3D—and 3D alone—at first. Rather than adding 2D graphics capabilities to its system and threatening lower performance, 3Dfx basically chose to focus only on 3D graphics at first. This meant that the company would have better performance on its 3D card than companies that tried to tack on 3D functionality after the fact.

- It leaned heavily on partnerships with larger companies. Sellers notes that when the company first started selling chips for PC boards, it wasn’t very well known, but it soon collaborated with Creative Labs and Diamond Multimedia, two major expansion board companies, to offer cards based on 3Dfx chips. (Diamond’s Monster3D, in particular, was an iconic graphics board during this era that was based on 3Dfx.) This created branding opportunities that helped boost the company’s recognition.

“Buying into 3Dfx is a very, very smart move for Sega. Not only is the company the best there is at what they do, but the technology is also well-liked by the developing community.”

— A Sega Saturn Magazine take from July 1997 on Sega’s deal with 3Dfx to produce the graphics hardware for the Dreamcast. The agreement was perhaps the most significant in the company’s history up to that point, but it was not to be permanently. Near the end of July 1997, Sega infamously backed out of the deal and went with NEC’s competing PowerVR technology instead. The wound may have been at least partly self-inflicted; Sega was reportedly none too pleased when 3Dfx, ahead of its initial public offering, revealed the existence of the deal in an investor document. Nonetheless, it was the first major knock of many the company would face. (Despite the ultimate failure of the Dreamcast in the market, PowerVR would become a key element of many mobile platforms, serving as something of the ARM chip of the computer graphics world.)

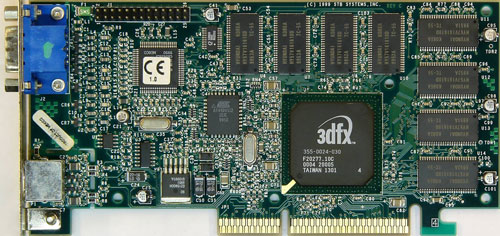

A Voodoo3 card. Unlike earlier models that relied on a third-party manufacturer, this was produced in-house by 3Dfx. (via VGA Legacy MKIII)

The acquisition that really screwed up a good thing for 3Dfx

In October of 1997, iconic 1990s gaming mag Next Generation, which is still well regarded today even though it hasn’t published in more than 15 years, published an article that seemed to finally assess the fact that this company came out of basically nowhere to dominate the gaming sector: “Is 3Dfx Here to Stay?”

With the recent bruises from the aborted Sega deal, it wasn’t the worst question to ask. Greg Ballard, the CEO of the company who was brought in from Capcom, put a suitably rosy picture on the situation.

“It has taken the industry—our competitors—14 months to even catch up with us, and within several months, we’ll be leaping ahead of them again,” he stated. “That’s what happens when you have a year-to-14-month lead on the industry. And we think our next leap in technology will be an improvement of an order of magnitude in the technology.”

Unfortunately for the company, the room for error was closing. Between 1996 and 1998, 3Dfx struggled to do much in the way of wrong, but it did have its stumbles. Among them was the company’s attempt to combine 2D graphics and 3D graphics on a single chipset type called the Voodoo Rush. The dedicated approach for which it was known made sense in the first generation, but didn’t work so well in integrated form, with the 2D half of the equation suffering. On the other hand, the Voodoo2 line, which continued the dedicated approach, was just as successful as the first model, while offering some of that expected leapfrogging.

However, the company’s leapfrogging capabilities would soon be hobbled by strategic shifts. At the tail end of 1998, the company announced it would acquire STB Systems, a major manufacturer of graphics cards. The result of the merger was that the company would stop selling its chipsets to other companies, acting as an original equipment manufacturer, or OEM, and instead would manufacture its own cards, starting with the Voodoo 3. The approach came at a time when competition from other major competitors, particularly Nvidia and ATI, was heating up, and the decision by 3Dfx to stop acting as an OEM for its latest chips meant that the company suddenly had both a new business model and a ton of competition.

The firm’s initial willingness to supply lots of manufacturers was effective, but it was one factor behind what became a massive glut in the graphics card space. CNET reported that by 1999, there were more than 40 companies producing graphics accelerators, a market complexity that meant any strategic errors would not be tolerated. On one hand, it meant that consumers were benefiting from the high level of competition, and this meant that things were improving on all fronts. On the other hand, this created a treadmill effect, one that 3Dfx was unable to keep up with.

“And so it really was a we're-going-to-do-it-all kind of strategy. And that's a big bet,” 3Dfx’s Scott Sellers recalled in the Computer History Museum’s oral history. “And when—just a little bit of slip as we did—we were a little bit late coming out with some of the next generation products and didn't have the runway to come up with the next generation products, which I think would have been very compelling on the market. But ultimately, we ran out of time.”

The company’s inability to execute on its pipeline, particularly on its next-generation Rampage endeavor, eventually cost it momentum, developer support (John Carmack didn’t exactly sound happy with 3Dfx by the end, did he?), and ultimately its lifeline.

Nvidia, which has emerged as one of the two main players in the graphics processing unit market (ATI, later bought by AMD, was the other), bought out 3Dfx’s intellectual property in late 2000. Nvidia, in a way, got a twofer deal out of the equation—3Dfx had acquired Gigapixel, a firm that had competed with Nvidia for a spot in the Xbox, just a few months before.

3Dfx created the treadmill, but only its competitors could keep up.

Currently, the GPU industry is facing a major shortage, one caused by reasons completely unrelated to the root causes of the GPU flood of the late 1990s.

Back then, a whole lot of companies saw an opportunity to bring high graphics capabilities to home users; today, GPUs are used for things as diverse as cryptocurrency, artificial intelligence, and automobiles. Supply pipelines, once flush with chips and cards, are running dry, with the rising popularity of crypto-mining a main factor.

A video clip featuring Valley of Ra, one of 3Dfx's demos of its rendering technology.

Clearly, none of this stuff was even a glimmer of an idea at the time 3Dfx shook up the GPU market in 1996. But it’s hard not to wonder whether the competitive spirit that the company fostered didn’t help to start off a world where GPU complexity would take so many alternate paths beyond graphics.

When asked if 3Dfx would have been able to take advantage of the general-purpose uses commonly seen with GPUs today, Sellers noted in the company’s oral history that things were just getting to the point where it might have been feasible to think in those terms.

“It was predominantly gaming. We didn't really have the ability to program the chips, per se, what you would need to have that kind of flexibility in terms of the GPU-like capability today,” he noted. “The product that we were working on at the very end before we sold to Nvidia, we did have a separate geometry chip that we were working on that perhaps could have done some of those types of things.”

Clearly, 3Dfx—once an icon of PC gaming—lost the plot at some point, only to be usurped by other companies. But I admit to wondering what might have happened had it been able to stay on that treadmill.

:format(jpeg)/2018/02/tedium021318.gif)

/2018/02/tedium021318.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)