Flying Patents

How the unidentified flying object inspired a flurry of flying saucer patents globally—and how one guy invented his flying saucer years before anyone else.

Tonight’s GIF comes from Plan 9 From Outer Space, which used high-quality materials for its flying saucers.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

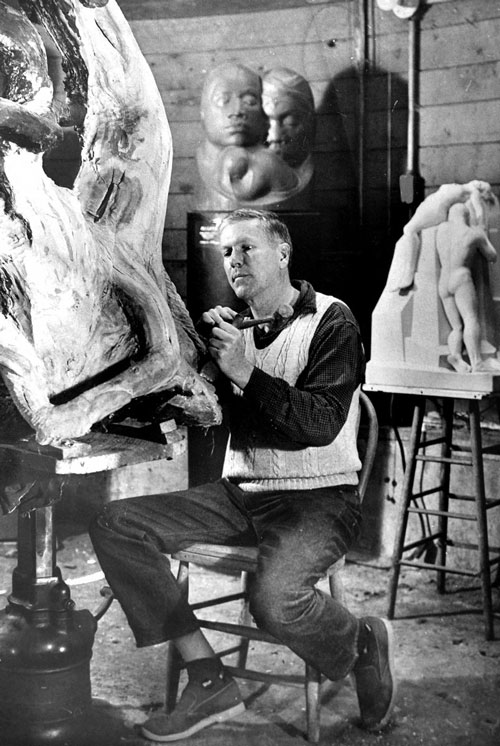

Artist and inventor Alexander Weygers. (via his Twitter page)

The guy who patented the basic concept of the flying saucer years before it was cool

The Dutch painter and sculpture artist Alexander Weygers, who grew up in the Dutch East Indies—a region now known as Indonesia—and spent most of his adult life in the U.S., was something of a 20th century Leonardo da Vinci. He had both an engineering and artistic background, his work spanned sculpture, illustrations, photography, and many other fields.

But perhaps his most unusual legacy might be the fact that, in 1927, he had conceptualized a device that predicted the insanity around flying saucers before they even had that name. (He called his invention the “discopter.”) And as an engineer, he did so with a practical eye toward the failings of the device he hoped to replace.

“Helicopters are vulnerable,” he said in an interview with UPI in 1985. “People were being killed in them during the 1920s. They go down like a brick. The saucer became the logical answer.”

Weygers’ creativity was driven by tragedy. In 1928, his wife died during childbirth, as did his son. The painful incident ended up pushing him closer to art, with the tragic incident inspiring some of his most notable sculptures.

A similar tragedy—the capture of his family, still in the Dutch East Indies, by Japanese forces during World War II—pushed him to complete his discopter project, which he had first started in the 1920s, in the early 1940s.

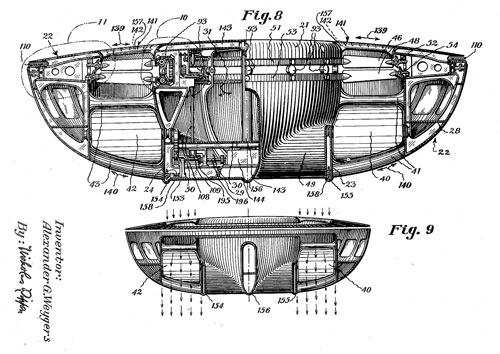

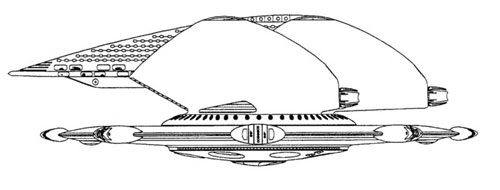

A patent drawing of Weyger’s Discopter. (Google Patents)

The idea was inspired not by spaceships or science fiction, but by a practical desire to create a vehicle that could be used to rescue people in incidents not unlike the one that faced his family members. His frame of reference was his own prior work.

He filed for a patent in 1944, and that patent was granted the next year. A key passage from that patent:

To a helicopter, a craft constructed on the principles of my invention bears a superficial resemblance in that both types are sustained by at least one horizontal rotor. From this point on, however, all similarity between the two types of flying craft ends. A craft embodying my invention is distinguished from a helicopter in that the rotor or rotors in my craft are enclosed within a substantially vertical tunnel, the rotor regarded as a whole is mainshaftless and the external form of the craft is not very different from the familiar discus of the athlete, in common with which the craft enjoys certain aerodynamic advantages characteristic of the passage of the discus thru the air. Not only the rotors and power plant compartments but all of the usual moving and fixed protruding parts, present in both airplanes and helicopters, such as stabilizing and directing means and otherwise, are entirely enclosed within the strikingly simple and cleanly streamlined contour line of the craft when regarded from exteriorly thereof in any elevation view, thereby concealing from the casual view such parts.

Alexander Weygers wasn’t trying to invent the flying saucer; he was trying to reinvent the helicopter, along with aviation in general, so that it could be used more practically. (It should be noted that the device was never built.) But the existence of everything that came afterwards meant that his name would forever be associated with futurism and science fiction—elements that didn’t actually inspire his invention.

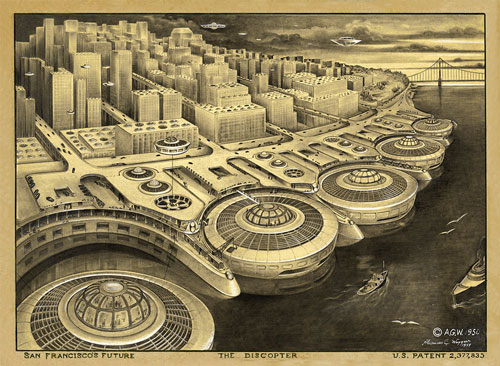

Weygers’ vision for the Discopter in San Francisco. He wanted to replace cars with flying discs. (via Discopter.com)

Case in point: After the flying saucer hit the public consciousness in the late 1940s, people noticed what Weygers had done. A 1950 article in the Allentown, Pennsylvania, Morning Call, dedicated column space to a dentist named Dr. Harold T. Frendt, who used the existence of the patent to argue against the existence of aliens. Frendt suggested that the patents were being used to create these saucers, despite his only evidence of them being used for this purpose was the existence of Weygers’ patent.

“They should be operated at high altitudes instead of exposing them for observation to the general public and the pro-communistically inclined, and thereby stimulating a trend of foolish speculation,” Frendt told the newspaper at the time.

Frendt’s statement is ironic, because he’s also speculating. There probably was no flying saucer.

“I was going to give him the V12 engine out of my Ferrari Berlinetta and John was going to give him his, and Alex reckoned that with those two engines he could make a flying saucer.”

— Beatle George Harrison, discussing the exploits of “Magic Alex,” a.k.a. Alexis Mardas, a man who The Beatles put in charge of a company called Apple Electronics, an offshoot of their record company that the band someday hoped would sell consumer electronics. (Another company named Apple would eventually take up that mantle. Maybe you’ve heard of it.) Mardas, who died earlier this year, denied ever claiming that he would build a flying saucer out of the engines from John and George’s fancy vehicles … among other things.

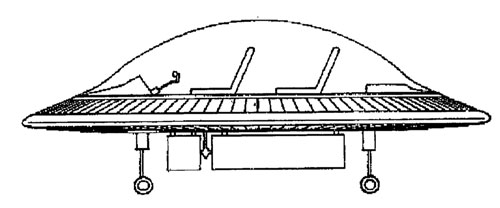

The patent document for this 2003 invention describes it as a “ring-shaped wing helicopter, which is similar to a flying saucer in appearance.” (Google Patents)

After the flying saucer hit the public’s imagination, the patent filings started flooding in

Last year, I wrote what I think quietly might be by favorite Tedium post of all time—in which discussed the sheer glut of umbrella patents ever since the creation of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in 1790, and why few of those patents have actually changed the way we use umbrellas.

The flying saucer, in its own weird way, has been exactly like that. As soon as there was a popular “spark,” the inspiration that had us looking up in the sky and wondering what if, the saucer was everywhere. It’s been keeping patent offices around the world busy ever since—first, with an early spate of flying saucer toys in the early 1950s that were clear precursors to the modern frisbee, and soon, in the form of aircraft clearly inspired by flying saucers, like this 1953 number and this helicopter/flying saucer hybrid. Eventually, though, flying saucers would become its own cottage industry in the world of patent offices.

Buried in the USPTO’s many classifications for airplanes and helicopters is the indexing code “B64C 39/001,” which represents “flying vehicles characterised by sustainment without aerodynamic lift, often flying disks having a UFO-shape.” Yes, USPTO got so many patents for flying saucers that it earned its own classification.

So how many flying saucer patents are we talking about? According to Google Patents, around 192 items are listed in this specific classification as being produced in the U.S., with three particular surges in their creation—an initial jump in the years between 1953 and 1956, a second wind between 1965 and 1971, and an unusually dramatic surge in such inventions between the years 2001 and 2004. USPTO handled 37 flying saucer-related patents during a particularly busy time in U.S. diplomatic history. (Why then? Was it the Afghan and Iraq wars? Was it 9/11? Was it the popularity of The X-Files? Or the popularity of the internet?)

No matter what way you slice it, there’s a lot to look at, and it’s entirely possible that due to the complexity of the patent system, this doesn’t cover everything. Fortunately, someone with a pseudonym and apparently a large amount of time already did a huge amount of curation for you.

Earlier this year, an Internet Archive user named Superboy collected more than 100 flying saucer patents spanning throughout the past 75 years or so. It took the user over three months to gather the documents from the U.S. patent offices and other patent offices globally, and is split up over two pages.

(Superboy helpfully noted that the documents prove “that humans have obtained and incorporated flying saucers for personal and secret use.”)

The kind of patent drawing that happens after you’ve watch too many movies set in space. (Internet Archive)

Some of the patents are decades old; others, from just the past couple of years. Some look like massive frisbees; others like tiny, squat planets; and others still look like they’ve taken clear inspiration from movies set in space. (And of course, Weygers’ groundbreaking craft made the list. It had to.)

Most patents were credited to individuals, with a handful of companies involved. Perhaps one of these individuals also worked on a rethink of the umbrella.

“This invention is a spacecraft propulsion system that employs photon particles to generate a field of negative energy in order to produce lift on the hull.”

— A man named John Quincy St. Clair, in a 2006 patent filing for a “photon spacecraft.” During the 2000s, St. Clair filed for dozens of patents for all sorts of bizarre things that can be best described as, well, clearly the work of the troll. (One with money, because filing for patents isn’t cheap.) Among his greatest hits: A “Magnetic vortex wormhole generator” and a “Walking through walls training system,” which comes complete with instructions on how to print the “training system” using a home printer. People have been wondering about this guy for years, and based on the existence of his patents alone, I’m convinced that aliens are real.

Of course, not every flying saucer patent has been produced by a weekend warrior, an eccentric inventor, or an engineer who turned tragedy into creativity.

Some of the largest companies in the world have occasionally taken interest in the flying saucer idea. In 2014, for example, Airbus invented a device that has a lot in common with the modern flying saucer, but also looks like a stealth fighter jet with a donut in the middle.

As CNBC reported at the time, it wasn’t intended for either outer space or the military—it was a reinvention of the passenger jet, even if a strange one that was intended to help reduce cabin pressure. And there’s a good chance we’ll never even see it.

“It’s just one of many ideas,” a company spokesman told Fortune. “It doesn’t mean that we’re going to be working on making it a reality.”

That actually sounds somewhat sedated compared to an attempt by the British Rail to patent a spacecraft that relied on “controlled thermonuclear fusion reaction.”

And of course, the future may show room for a flying saucer—or at least a flying car—yet. As Bloomberg Businessweek reported last year, Google co-founder Larry Page has been investing in the idea of flying cars for years through his startups Zee.Aero and Kitty Hawk, with a guy named Alexander Weygers cited as an early inspiration for what could come next.

Earlier this year, Kitty Hawk released a video for a product that, if you squint hard enough, shares a lineage with what Weygers did way back when, with maybe inspiration from all the things that have come along since.

Someone is gonna crack this flying saucer thing, and it’s not gonna be the aliens.

:format(jpeg)/2017/10/tedium101017.gif)

/2017/10/tedium101017.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)