Security In Stereo

Car stereos have historically been both valuable and easy to spot in an idle vehicle, making them a key target for thieves. Why has that changed?

$40M

The amount that the American Mutual Insurance Alliance estimated that car insurers paid on claims related to car stereo theft in 1969, according to a 1970 New York Times article. The problem of car-stereo theft caught insurers flat-footed, according to the Times, which noted that insurers were initially unsure how to handle the claims when they first started popping up in the 1960s. “Even with factory‐installed models, all it takes is the unscrewing of a few bolts. It can be done in about three minutes,” noted John Wrend, the manager of the Alliance’s Mutual Loss Research Bureau. “The thief often has time to rip out the speakers and break into the glove compartment for the tapes.”

Car stereos: Expensive, flashy, and relatively easy to steal

Dating back to the 1930s, the car stereo has a fairly long history and is known for fostering an important array of innovations—music, as the iPod proved roughly a decade ago, is a great way to win over the public.

But like white earbuds in 2004, car stereos were kind of an obvious tell. They revealed an easy target in the car, one that any passer-by can clearly see—whether the music-playing device is snazzy or merely does the job.

It wasn't always this way. Early on, the tinny audio and the lack of expandability (no vinyl, mostly) made the devices glorified radio tuners at first. But as improvements began to show themselves—from the “Seek” button to 8-track players, and particularly, the cassette tape—the risks of car stereo theft rose. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, things got really bad. One 1983 New York Times article reported that NYPD police officers had recovered $115,000 in stolen stereos in a two-month period alone.

Even today, it’s not hard to find videos of car stereo theft on YouTube—whether it’s a consumer victory or just some guy showing off his ability to swipe a dashboard device. Security-cam footage, like this clip of a guy who manages to break in a car and steal a stereo in a mere 10-second period, at times makes this kind of theft look downright easy—and makes you never want to store anything valuable in your vehicle ever again.

For car owners, that’s pretty distressing, but there are much more cathartic things to watch as well, such as this clip of a guy who ran down a couple of car stereo thieves. (Of course, it’d sure be nice if car owners didn’t have to chase down thieves in the first place.)

In some ways, the problem with the car stereo was its design—its sheer placement, meant for maximum convenience as you go 15 miles over the speed limit on a long stretch of highway, also makes it a sitting duck.

That’s why car stereos are so fascinating from a security standpoint. When it came to securing them, a lot of interesting ideas were tested.

(via Popular Mechanics)

Five examples of car-stereo security devices

- Car-stereo theft, clearly already rampant in the early ‘70s, necessitated some clever approaches. One of those, a Kustom Kreations slide-out 8-Track player, cleverly works in a variety of different settings—home, boat, or car—and did so without the use of any wires at all, according to Popular Mechanics.

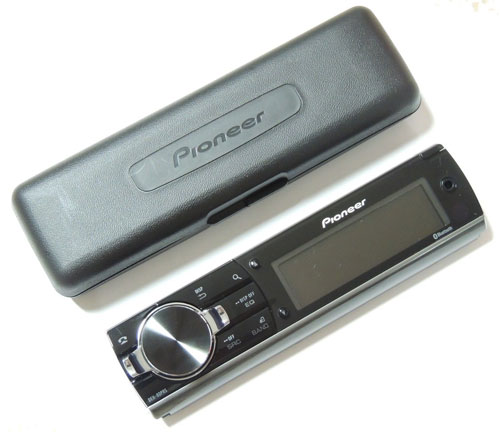

- Pioneer’s 1989 introduction of the detachable faceplate proved an extremely memorable sign of security for many car owners. Other companies were doing the same thing around that time, but Pioneer saw more success. “Pioneer's entire panel is detachable, leaving the stereo with a blank face that may appear as if no equipment is installed,” the New York Times noted in 1990.

- Car security systems, obviously, grew in popularity around the time of the aftermarket car stereo, so it was only a matter of time before someone combined the devices. Sanyo’s Viper, released in 1985 (and not to be mistaken for Rep. Darrell Issa’s same-named cash cow), both worked as a stereo and a security system.

- Later devices, especially those put into cars by manufacturers, often relied on security codes to ensure that only the owner was using the vehicle. Problem is, these codes aren’t easy to find after a car has gone through the used-car cycle more than once, and that means you’re often looking on sites that aren’t the most scrupulous to figure out how to unlock the codes.

- If a removable faceplate isn’t an option, there’s always the option of getting a fake one. Mock faceplates, such as the Incognito Car Stereo Disguise Kit, are designed to look cheap, even when there’s a nice stereo hiding behind the facade. Here’s one YouTuber that’s modernized the strategy.

(via JustBuySpares)

What the detachable faceplate, a stereo-security staple, teaches about modern-day security

There are a couple of modern-day metaphors that come to mind when thinking about the security approach introduced by the detachable faceplate, a car-stereo phenomenon of sorts that gained notice in the early ‘90s for its ability to separate the device from the security need.

In some ways, it works very similarly to two-factor authentication, or perhaps a key fob—you won’t be listening to your Bee Gees disc unless you have that cover, thanks.

But it’s not the only security policy in which car stereos can claim some inspiration.

In his 2003 book, Beyond Fear: Thinking Sensibly About Security in an Uncertain World, famed security technologist Bruce Schneier compares the strategy used with removable faceplates to that of garment tags on clothing that expel colored dye on the clothes when stolen.

This, he says, is a form of security called “benefit denial”—the idea being something of a theft deterrent. If you steal something, it becomes useless.

But Schneier, being a security pro, still sees the failings of this sort of approach.

“Many of these countermeasures—like the dye tag on garments—depend on the secrecy of the tag-removal system to be secure,” he writes in the book. “If shoplifters can get their hands on a portable tag-removal machine, as some have, the countermeasure no longer works. And there are limits: People who remove their car stereo faceplate when they’re not driving may still get their windows smashed by thieves who find it easier to break the window than to check first.”

Nonetheless, the strategy is effective enough that a variation of it exists for modern-day smartphones—in the form of the “kill switch,” which allows users to remotely wipe a device and make it impossible to use without the username and password of the original user. The result is that new phones are much less likely to be stolen because the devices are effectively useless out of the hands of their original owners.

Car stereo faceplates are clearly the best-known security measure for stopping theft (well, minus Darrell Issa’s Viper voice), but it ultimately may have only proved a transitional solution to the problem.

The real solution came from the mainline auto industry, which, as NPR noted in a 2009 article, accidentally solved the car-stereo theft problem by integrating the vehicle’s audio systems in a very complex way. It’s of no benefit to a thief to steal a stereo that only works in one kind of car.

“Not many thieves can offer installation on a flip-screen navigation/video/stereo system with a Bluetooth-compatible computer interface operating over fiber optic cables,” NPR’s Laura Sullivan noted. “Done right, it should also be compatible with OnStar and a wireless router.”

Since the piece, cars have only gotten more sophisticated and advanced, too—think on-board dash cams and the like. The situation is such that you might have an easier time taking the passenger seat than the stereo on some modern-day models.

Combine that with the improvement in portable audio—odds are good that your smartphone is more capable as a music player than your ’95 Saturn—and it’s clear that the bottom fell out of the black market car stereo trade pretty fast.

Sure, the solution isn’t perfect. New routes will be opened for those who want to cause trouble. Maybe the thieves will decide the car is a better target than the stereo. Maybe the smarter digital brains and Ethernet-based central nervous systems inside of modern vehicles will open up new routes of attack, like hacking. (It’s worth noting that the National Insurance Crime Bureau’s “Hot Wheels” analysis of most stolen cars included a couple of recent models.)

Nonetheless, though, the push toward integration teaches one thing about security: Sometimes, the best possible security method is to find a way to mitigate the problem altogether.

You can’t steal a car stereo if you don’t know where it is.

:format(jpeg)/2017/06/tedium112916.gif)

/2017/06/tedium112916.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)