We Screwed Up

Standardization has long ruled the world of screws. Despite that, screw standards differ between North America and the rest of the world. Here's why.

69

The number of screws in a full screw kit for the iPhone 6S sold on Amazon. (Yes, I counted. It was tedious.) No word on how many screws the iPhone 7 has, but the iPhone 6 had just 52 screws, according to one online seller. Screws have periodically been a source of controversy for Apple, particularly when the company introduced pentalobe screws with the iPhone 4 at a time when pentalobe screwdrivers were very rare. The screws were seen by repair experts, such as iFixIt’s Kyle Wiens, as a way to prevent users from repairing their own devices.

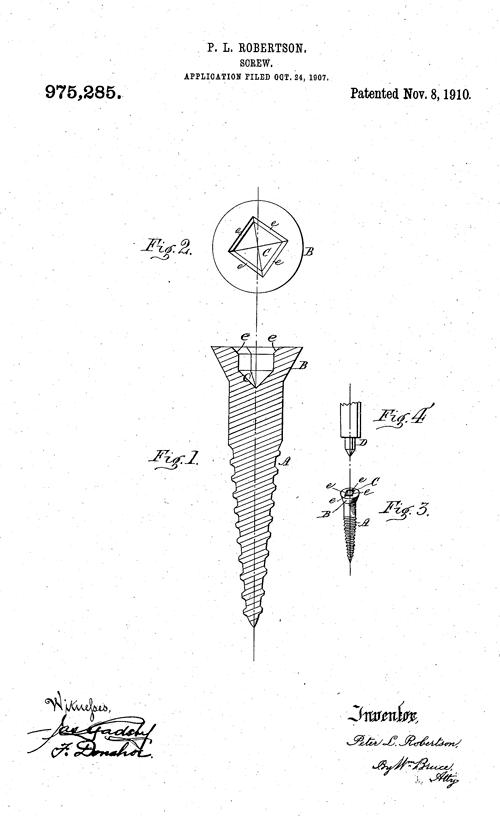

Five different varieties of screws that weren’t popularized by a guy named Phillips

- The square-headed Robertson Screw predated the Philips screwdriver by about 30 years, and for decades it was more common than the Philips in the U.S., which eventually won out not due to a more efficient design, but because of licensing drama. See, Henry Ford wanted inventor P.L. Robertson to license out his screw design. Robertson refused, and that led the design to lose out to the Phillips screwhead in the U.S. market. The Robertson screw is still popular in Canada, however.

- The hex socket set screw, named for its six-sided hexagon design, isn’t named after a person, but its corresponding tool is. The Allen wrench, named for William G. Allen, has existed for more than 100 years. The reason the wrench is named for Allen rather than the socket? Because the hex screw predates the Allen wrench by a few decades.

- The Bristol screw, which is now called the Bristol Spline Drive, has an unusual spline-driven circular design that is claimed to be excellent at producing torque. The invention, which initially had an Allen wrench-style design, dates to 1911, with the invention credited to a guy named Dwight S Goodwin.

- The Torx screwdriver, which first appeared in 1967, introduced a star shape that has become fairly common in certain technical uses, such as cars, bikes, and consumer electronics. Unlike a Phillips screw, it’s designed not to fall out, and at first, to prevent people from unscrewing it, the screwdrivers were proprietary. (It’s similar to Apple’s pentalobe screw, except pointed instead of rounded.) They also came in handy for guns. “Before Torx, which appeared in 1967, all firearms relied on slothead screws, which were designed to make ordinary shooters miserable and enable gunsmiths to drive around in Bentleys,” Field & Stream‘s David E. Petzal wrote.

- Perhaps the most interesting and unusual screw design in the past few decades is the Outlaw Fastener, a multi-tier screw that is akin to combining an Allen wrench with a three-layer cake. It was the subject of a successful Kickstarter campaign in 2013. The design, if fairly advanced, isn’t totally new; it appears to be the direct descendant of the Uni-Screw, a design that dates back to the 1960s.

“It is well known to persons who use screws that if the nicks are narrow and shallow it is difficult to drive the screw without the screw-driver slipping out of the nicks, and if the nicks are wide and deep to afford a good gripe, the head of the screw is weakened, and the screw-driver is liable to slip out sidewise and deface the finished surface of the work, and if the screw-driver is the same width as or wider than the head of the screw, the countersink work is liable to be defaced, and the angles of the screw-driver are often broken.”

— Engineer John Frearson, in his patent application for a screw drive head that used a cross style very similar to the more commonly known Phillips head screwdriver. The Phillips screw, however, has a slight curvature in the center, which makes it so that when the screw is in all the way, the screwdriver would inevitably fall out (or if you’re me, you would continue twisting anyway until you’ve fully stripped the metal and made the screw useless). Frearson screws, a 20th-century innovation based on John Frearson’s 19th-century work, are popular with boating types.

The U.S. debated screw threads for more than 30 years

The history of the screw is surprisingly diverse and unexpected.

It dates back thousands of years, to ancient Greece, when it’s claimed Archytas of Tarentum invented an early version of the device. It has the fingerprints of Leonardo da Vinci, and was a key part of the Industrial Revolution.

But in the midst of the peak of innovative efforts around the screw, one that saw the creation of both the Robertson and Phillips screws, the U.S. government … well, they spent a lot of time researching screw threads.

(For people who don’t regularly screw stuff in, the thread is the pointed metal line that twists around the bolt. It’s what makes a screw a screw and not a peg.)

In 1918 Congress passed a law establishing an organization called the National Screw Thread Commission, with the goal of ascertaining consistent standards for screws. The goal of this effort, which you might guess given the timing of the law’s passage, is military-related: As you might guess, the military uses a lot of screws, and inconsistencies were apparently bad enough after World War I that Congress had to do something about it.

John Q. Tilson, a Connecticut congressman, argued that the measure was necessary due to the problems a lack of consistent screw thread were creating. He also made the case for businesses—who he argues also will benefit from screw compatibility.

“Private manufacturers, however, desire this done just as much as everybody else,” he said, according to The Journal of the Society of Automotive Engineers. “They would like to have the standard of tolerance for screw threads all over the United States.

The law, of course, passed, and we had the National Screw Thread Commission, perhaps the most obscure bureaucratic organization to ever exist.

But it had a perfectly good reason to exist. A 1926 New York Times article about the commission highlighted the 1904 Baltimore fire, in which fire departments from other major cities came in to help. Unfortunately, the other cities had hoses that were incompatible with the screws used by Baltimore, making their help useless.

The article noted that the government was working close with the U.K. on the issue, and differences between those two countries did a lot to underline the problem:

There is, however, a fundamental difference in the angle of the thread of the two systems. This is 60 degrees for the American and 55 degrees for the British thread. Still another difference is that the American thread has flattened crests and roots, whereas those of the British thread are rounded.

(via Pixabay)

This difference surfaced essentially because the U.K. had created its own standard, the Whitworth Thread, but an American thought he could do things better. In 1864, William Sellers introduced the screw design for the American market that borrowed inspiration from Sir Joseph Whitworth’s design, but pitched a new path forward.

Now, the U.S. was trying to convince the rest of the world that Sellers’ design was the way to go. And it took a long time to sell them on the idea. The National Screw Thread Commission was active for three decades, partly because of all the details to go over, and partly because another war threw a wrench in the mix. (We haven’t even talked about wrenches!)

What eventually ended the commission’s long reign of terror was a deal with Canada and the U.K. to embrace the 60-degree screw thread, something that’s called the Unified Thread Standard. (The Second World War, of course, highlighted just how big a problem the different screw standards were.)

At the same time the U.S. was working out its thread standard, the rest of the world was doing their weird Metric System thing, and around the same time as the launch of the Unified Thread Standard, the International Organization for Standardization was getting off the ground, and of the first tasks they took on was standardizing the screw. The good news is that the screw design they chose screws in at the same angle as an American screw. The bad news? They set the design on the metric system, when the U.S system was based on inches.

So much for a unified system, though Americans don’t seem to mind it. (It would be hilarious, though, to see shoppers at Lowe’s confused if one day they picked up metric-standard screws rather than the American ones they’re used to.)

In 1960, when the U.K. moved over to the metric system, the Americans lost an ally on the screw thread front.

So it’s basically us and the Canadians, and the Canadians are using those weird square screwdrivers anyway.

In a lot of ways, the perils of the screw highlight some important modern debates we’re having with technology.

Specifically, regarding the 3.5mm headphone jack, that thing Apple is apparently trying to kill.

Let’s put the company’s argument in screw terms: The headphone jack, as it currently stands, is the musical equivalent of a Phillips screwdriver, better than what we originally had (flathead screws) but also greatly lacking in terms of what could be (no screws whatsoever—they’re getting rid of the screws over at Apple).

They’ll still give you an option for screwing stuff in for now—they’re using pentalobe screws, so you’ll have to use an adapter so your Phillips screwdriver still works. But in the long run, you better plan to throw away your screwdrivers altogether, because where they’re going, you won’t need them.

That argument is not a great one, but it’s understandable why they might want to change things—clearly a Torx screw is better than a Phillips, but we’ve already committed to the standard.

Apple’s counter-argument: Screw the standard! Why not give people something better that improves their lives?

And as we know, Apple has never been one to follow standards. They invented a new screw just to piss people off.

:format(jpeg)/2017/06/tedium091516_new.gif)

/2017/06/tedium091516_new.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)