The Neighbors You Love to Hate

The rise of homeowners associations is sort of like a microcosm of pettiness and slights, except way dumber.

“While each homeowner has the right to use its property as it chooses, such right is not paramount to the rights of all other homeowners. And such use and enjoyment of one’s property should not be to the detriment of other homeowners’ right to use and enjoy their property.”

— A quote from the letter that Halloween fanatic Nick Thomas received from the Ashbury Home Association of Naperville. Thomas’ annual haunted house display, which has grown immensely over the years, went viral last year thanks to a video showing a synchronized light show featuring Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody,” something that helped Thomas’ display get on Good Morning America. In other words, it was a victim of its own success. The letter went on to explain: “[R]ules and restrictions are a part of common interest associations like Ashbury, and they are there to protect the value of each of our property.”

Why are homeowners associations so heavy, anyway?

Let’s talk about this in terms of one of the greatest British films of the past decade, Hot Fuzz. Edgar Wright’s spot-on satire of cop films often gets credit for its whip-smart dialogue and ability to tie action-film tropes into a nontraditional setting, but one thing it doesn’t get enough credit for is its hilarious mockery of homeowners associations.

Throughout the film, numerous people mysteriously die in unusual ways, leading the intrepid cops (played by Simon Pegg and Nick Frost) to try to link together any clues to figure out if the crimes are connected—and why. Near the end of the movie, the truth comes out (spoiler alert): The victims were killed by members of the community association because they were seen as blights on the town ahead of an important contest—an extremely callous way to treat other human beings.

If that sounds like an over-the-top way to portray homeowners associations in film form, perhaps it is. But sometimes, the HOAs make it so easy! An example of this comes from a 2010 court decision involving truck owner A.J. Vizzi.

The Florida resident had years earlier confirmed with his HOA that parking his truck in his driveway wouldn’t be a problem. But after doing so for years, the association decided that they weren’t cool with it, and then proceeded to sue Vizzi to get him to stop.

Vizzi won the case, but the HOA appealed. Vizzi won again. But the best part about all this is that the HOA had to pay his legal fees, which by this point totaled up to an absurd $187,000—a particularly painful sting because HOA costs of this nature are handed down directly to the residents.

“I couldn’t believe I had to go hire an attorney just to defend myself against this ... meritless lawsuit,” he said of the suit.

66.7M

Five reasons homeowners associations have become such a prominent part of American society

- Racism. No, really. Prior to legal precedents that outlawed segregation in the 1940s and 1950s, homeowners associations and similar covenants were used to prevent ethnic groups from living in certain communities. An example of a city that faced these types of issues was Seattle. Things changed in 1948, when the Supreme Court ruled such covenants unconstitutional in Shelley v. Kraemer. Fortunately, this is not a current reason for homeowners associations (thanks to the later passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968), but it did play a role in their early formation in some cities.

- Environmental laws. The U.S. Clean Water Act of 1977, which required that communities have places to store excess stormwater, was a key catalyst for the creation of such associations, as it was a heck of a lot easier to build a place for excess stormwater throughout a broader community than building a number of individual ones on each person’s property.

- Government and business influence. In 1964, the Urban Land Institute, a nonprofit organization, published a technical document called The Homes Association Handbook, which basically outlined the concepts behind modern homeowners associations. The document, which was paid for by the U.S. Federal Housing Administration, the National Home Builders Association, and a wide variety of federal regulatory bodies, became essentially the constitution for many homeowners associations nationwide.

- Declining availability of land. By the 1970s, the land already available was becoming scarce—and as a result, we were running out of places to put new people. By leasing land to associations that controlled the overall maintenance of a neighborhood, municipalities could more effectively use the land they had while making more money off that land.

- Property value, duh. For all the frustrations about over-the-top rules that commonly arise with HOAs, they ultimately play an important role in ensuring the quality of the neighborhoods, and thereby, the value of the home. Most homeowners want something that remains valuable, and holding things up to a certain standard helps make things easy. While HOA fees generally fall between roughly $200 and $400 per month, the cost can pay for itself if the value of the house remains high.

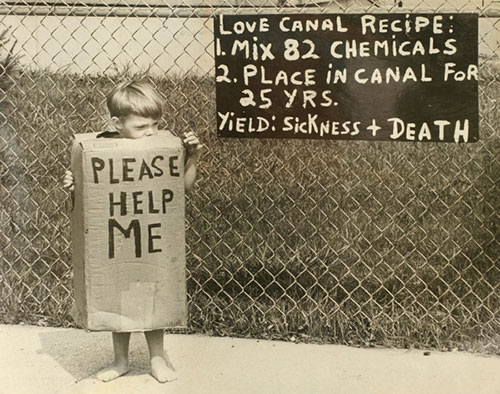

Love Canal: The homeowners association that changed history

Not every story about homeowners associations ends in grumpy adults fighting about inconsequential matters. Sometimes, such organizations are the best way for a broader community to fight against a larger, more dangerous force.

Love Canal in some ways is the perfect example of the potential for the value a homeowners association can bring to a neighborhood. The community, located in Niagra Falls, New York, found itself dealing with a major environmental crisis when it was discovered that the neighborhood decades earlier was used as a chemical dumping ground—with the neighborhood’s primary school right at the center of that dumping ground.

One concerned parent, Lois Gibbs, noticed her son was getting sick, and soon, she figured out why—after reading a newspaper article, she learned of the contaminants left behind from Love Canal’s time as a toxic waste site. Gibbs, concerned about the local school’s proximity to a dump site, struggled to convince administrators to let her move her son to a different school. The school argued that there was no evidence that people were getting sick because of the school’s location. By talking to her neighbors, Gibbs soon found plenty—in the form of illnesses and genetic defects among local residents.

“Who would build a school on top of a dump? Who would build a playground on top of a dump? And why didn’t anyone tell me?” Gibbs said in a 2013 interview with the Center for Public Integrity.

Slowly getting organized as it became clear just how screwed up the situation was getting, local residents formed the Love Canal Homeowners Association in August 1978. The group geared up for a fight—a fight to prove to both industry members and the government that the only way to solve this problem was by getting everyone out. The state had already started to move out pregnant women and young children; the association wanted to get everyone out and ensure that residents were being taken care of both by the state and the federal government.

It was a homeowner’s association that existed essentially to dissolve the neighborhood—by gathering research, organizing data, and proving the risks in staying in Love Canal. Gibbs was at the front of this movement, and became the president of an association representing 900 families.

Soon after the group formed, president Jimmy Carter declared the neighborhood an emergency area. It took nearly two years and a major uphill battle, but the group eventually persuaded the federal government to move the neighborhood’s many families elsewhere.

The work of the neighborhood association had lasting effects for Love Canal and similar communities; it led to the passage of the Superfund law, which created a plan for cleaning up toxic waste incidents. And Gibbs became a major figure in the environmental world, forming the Center for Health, Environment, and Justice in 1981.

“I just thank God that we had Lois at the time,” Luella Kenny, a former neighbor of Kenny’s who serves on the nonprofit’s board, told the Center for Public Integrity. “You just had never heard of people being able to take over and be able to win and to beat the government.”

In the end, though, you have to wonder: Do HOAs really have the benefits that many say they do?

That’s a question that’s up in the air. The negative reputation of HOAs comes across as a bit too cultish for some, and that leads some to skip out on real estate offerings included in HOAs, because they don’t want the hassle. Buyers who might otherwise be interested in homes in certain neighborhoods may choose to skip out.

And if the HOA is inactive or has fallen asleep at the wheel, you’re on the hook for all the stuff that the HOA hasn’t paid for.

One thing is for sure: HOAs evoke a lot of passion and a lot of dumb rules. Just ask Halloween enthusiast Nick Thomas.

:format(jpeg)/2018/04/ghticcz8g1hiiz22awnf.gif)

/2018/04/ghticcz8g1hiiz22awnf.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)