Live and Let Dye

These days, artificial food coloring is seen as a major health risk—admittedly, for good reason in some cases. But, shockingly, things used to be way worse.

"Companies use food coloring to simulate the presence of a fruit or a vegetable. To be honest, they’re used to cheat people—to mislead consumers. It’s cheaper to use these than the real thing."

— Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) Executive Director Michael Jacobson, discussing the usage of artificial food coloring in food items across the spectrum. Last year, CSPI highlighted a study on the amount of food dye currently in use in brand-name foods. The study found that, while Trix has a pretty startling 36.4 mg of artificial coloring in each serving, that's still less than Captain Crunch's Oops! All Berries, which has 41 mg. Oops.

You think food coloring is bad now? Here's what it used to be like

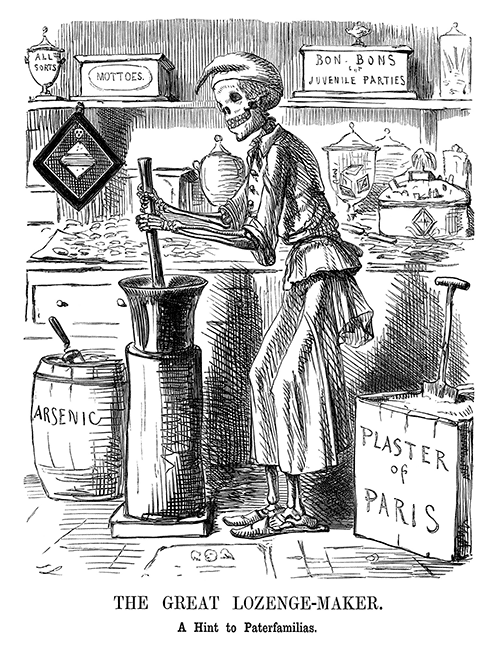

It's common today to hear food experts raise concerns about the amount of artificial dyes in our foods today, but to be fair, we're in a lot better shape now than we were in the Victorian era.

When cities began to pick up ground as the industrial age came to a start, food vendors knew quickly that they had to put bold, beautiful colors out there to ensure customers would buy. Problem was, many such vendors were using materials that were far from edible.

Eventually, a German scientist, Frederik Accum, finally took a big step towards calling out the food industry for its nefarious practices. After living in London for decades and seeing the way food was messed with, he finally became disgusted enough to write a book on the matter, A Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons. In the book, Accrum noted that vendors would dye spent tea leaves, reuse spent coffee, and contaminate both wine and cheese with lead.

Accum, who named actual vendors, found himself facing so much legal trouble soon after the publication of his book that he had to move back to Germany.

Fortunately, Arthur Hassall was there to follow in his footsteps. Hassall, a chemist and microscope expert, was able to prove that the food-maker Crosse and Blackwell was using copper to make its pickles look greener. It was a pretty great gotcha that helped lead the British government to pass the Food Adulteration Act in 1860.

"Hassall's work showed that adulteration was the rule rather than the exception and that adulterated articles were often sold as genuine," The Royal Society of Chemistry's Noel Coley wrote of Hassall. "He was meticulous both in his scientific work and in accurately recording where and when the samples had been purchased."

(Of course, good marketers know how to flip a bad situation into a good one. Crosse and Blackwell, soon after getting shamed by Hassall, advertised the fact that its pickles no longer were made with copper, and sales went through the roof.)

80+

The number of artificial dyes in use in 1906, the year that the U.S. Congress passed the Pure Food and Drugs Act, a law that became the starting point for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The FDA played a key role in reining in the number of approved dyes for use in foods, drawing the number down to around 15 or so in the 1930s and ever further in later decades, according to Forbes. Now, just seven approved colors remain.

Five natural materials you can use to dye foodstuffs

- Saffron has a history that dates back thousands of years, and despite being fairly expensive for a spice, it remains one of the most popular ways to turn bowl of rice from boring white to colorful yellow. (If you're going yellow or orange, tumeric is also an option.)

- If you like red-colored food, you're eating bug extract without even realizing it. For years, cochineal extract has been a key way that food has gained its bright red coloring. Using said bugs, which tend to grow on cactuses, is extremely common, but generally grosses people out when you tell them: Back in 2012, Starbucks had to announce to the public that it would stop using the red dye after a public outcry over the fact that one of the chain's drinks wasn't vegetarian.

- As you might guess, natural green dye is pretty easy to come by, as long as your goal is to give food a vegetable-style hue. The secret to going green naturally is simple—just blend up some boiled spinach.

- Creating a natural blue dye is extremely tough—so much so that Trix is dropping blue colors from its cereal when it goes natural next year. But it can be done! The best strategy for going blue, according to Whole New Mom, is by mixing red cabbage extract with baking soda. And the food science world is still buzzing about the FDA's decision to allow spirulina extract, a natural blue-green color that comes from algae, to be used in candy and gum.

- If you wanted to make white candy, your options used to be extremely limited. Really, you only had one option: The synthetic titanium dioxide. But in 2009, the Danish company Chr. Hansen announced the creation of a calcium-carbonate based white dye.

That time the butter industry lobbied for pink margarine

Before the 20th century, it wasn't too common for corporations to lobby for stuff, and when they did, it often created great debate about whether Congress should get involved in business affairs at all.

One of those debates came immediately before the passage of the Oleomargarine Act in 1886. The law came as a result of an aggressive dairy-industry campaign against the rising popularity of margarine, which had proven a inexpensive alternative to butter.

The reason margarine became so viable was in large part due to the usage of yellow dye. When margarine was first sold in stores, it was colored white and looked closer to lard than butter, which meant that many people found it unappetizing. The dye fixed that problem without adding much in the way of extra costs. Milk, which butter uses, was expensive; animal and vegetable fats, which margarine relied on at the time, was not.

Soon after margarine-makers got the dye involved, the dairy industry sensed a threat, and went to Congress in a push for legislation that would protect Congressmen from dairy hotbeds like Iowa and Wisconsin were particularly harsh on margarine.

“If I could have the kind of legislation that I want, it would not be a source of revenue, as I would make the tax so high that the operation of the law would utterly destroy the manufacture of all counterfeit butter and cheese as I would destroy the manufacture of counterfeit coin or currency,” Rep. William Price (R-WI) said of his push for the Oleomargarine Act.

As bad as the law—which taxed margarine and effectively banned it from being colored yellow for nearly 70 years—was, it was nowhere near as bad as some of the laws against margarine passed at the state level. For a time, a number of states were requiring the naturally white margarine to be sold with a pink dye—with the obvious goal of making the substance look disgusting.

The Supreme Court quickly put the kibosh on this idea.

"In a case like this it is entirely plain that, if the state has not the power to absolutely prohibit the sale of an article of commerce like oleomargarine in its pure state, it has no power to provide that such article shall be colored, or rather discolored, by adding a foreign substance to it, in the manner described in the statute," the court ruled in the 1898 case of Collins v. New Hampshire.

While margarine-makers were able to fend off the naked attempt to destroy their imitation butter, the ban on coloring the margarine yellow proved more difficult to shake. The solution for a time involved distributing packets of dye with the margarine, which was admittedly a bit awkward, but helped improve the gross-out factor of white fat spread.

Eventually, the passage of time worked in the favor of the margarine industry, and the federal regulations were repealed in the 1950s. By 1967, all of the state-level regulations that had limited the sale of margarine went away for good, too. The last state to drop its anti-dye strategy? Wisconsin, of course.

For all the health concerns that still linger around various kinds of food dye—be they artificial, natural, or bug-based—the truth of the matter is, we're suckers for a little bit of color.

Case in point: The rise of the red velvet cake. In the 1930s, the Adams Extract Company—which creates artificial dyes and flavorings—was smarting from a decline in business due to the Great Depression.

Instead of taking this situation lying down, the company came up with a way to use its dyes in a novel fashion: They released a recipe that relied on red food coloring and butter extract to create an extremely rich cake, then offered up that recipe to grocery stores around the country.

The result became legendary and widely imitated—artificial coloring or no.

:format(jpeg)/2018/11/eihmltbehpottagzpruv.gif)

/2018/11/eihmltbehpottagzpruv.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)