Diaspora: Not Just A Forgotten Social Network

When a culture permanently shifts to a new home, a diaspora spreads—and sometimes it creates a fascinating cultural pocket of its own.

So, what the heck is a diaspora, anyway?

We all started somewhere, and sometimes it wasn't by choice. Over the generations, notable cultures have moved long distances away from the lives of their ancestors, the experiences they grew up with, and the cultural norms that pervaded their prior lives.

The result of these movements—which can represent issues such as emigration, religious persecution, political strife, forced labor, or slavery—is that they create significant cultural imprints on the cultures that they touch.

In the U.S., perhaps the most well-known diaspora is the population shifts seen during the rise of slavery, affecting both African emigrants and Native Americans. Beyond the issues of discrimination and civil rights that have lingered sense—has also created large, permanent effects on American culture. Some of them were positive, others were not. But our society is different because these cultures became ingrained in our own over time.

(Another example is the Jewish diaspora, which has been going on long before the modern world even took shape.)

The common word used to describe this sort of situation is "diaspora," and it's a loaded term, as it emphasizes a cultural shift that was forced upon people who were forced to leave their homeland without a choice. In recent years, the term has become disconnected from this history, with "diaspora" being used to describe essentially any kind of move.

"The experience of being scattered is central to the identity of the ethnic groups that the word has traditionally been used to describe, and some fear that the collective tragedy that these peoples experienced will stop being commemorated if every community lays claim to the word," explains the International Diaspora Engagement Alliance.

There's a lot of difficulty that comes with diaspora. For the interests of this piece, we're focused strictly on the effects of the spread.

650k

Unexpected ethnic populations in North America

- The Mexican border city of Mexicali has one of the largest populations of Chinese immigrants in the entire country, with more than 5,000 immigrants coming to the city from parts of China, and many other native residents of Chinese descent. The city's vibrant Chinatown also highlights another fascinating fact—the city, which now has a population of nearly 700,000, was built in the early 20th century thanks to the help of Chinese immigrants. It's created for some interesting meshing of cultures: If you're in the mood for shark fin tacos,you can find them there.

- Michigan's Upper Peninsula may represent be one of the most unusual cultures in the United States. Relatively isolated due to the lack of large cities and its status as a peninsula not directly connected to any population centers, the U.P. has one of the largest concentrations of Finnish immigrants in North America, which is surprising as there are relatively few Finnish-Americans.

- Canada's fairly large Icelandic population—nearly 100,000 Canadians can claim heritage from the country—is thanks in large part to a volcano eruption. In 1875, the ashes of Askja drew many Icelanders away from their homeland and to the provinces of Manitoba and Alberta, with many residents ending in in an area around Lake Manitoba known as "New Iceland." While they kept the cultural identity, one thing they didn't keep were the patronymic last names. The city of Gimli, Manitoba—about an hour north of Winnipeg—holds an annual Icelandic festival.

- Before Cuba went Communist, it was a popular place for Jewish emigrants after World War I, when the demise of the Ottoman Empire destabilized the population in Europe. During the 1920s, more than 20,000 Jews moved to the country—and while that population thinned out after the Cuban Revolution, more than 1,500 residents still live in the country. Raul Castro even hangs out with them every once in a while.

- Alaska's fishing industry has a history of driving migrant workers to the region—most notably the state's sizable Filipino population, which was borne of the the state's salmon canneries. Some believe that Filipino-Americans will one day represent a quarter of all Alaskans.

"Those of us born in the Eurasian country are devoid of any association acknowledged by Cuban authorities and any socialization among us 'immigrants' tends to be sporadic and fragmented."

— Dmitri Prieto-Samsonov, a self-described Cuban-Russian or Russian-Cuban, discussing the country's fairly unknown Russian diaspora in the Havana Times. The country counts hundreds of Russian immigrants, many of whom moved to the country after the Cuban Revolution, but despite Cuba's ties to Russia, these residents tend not to have close connections to one another.

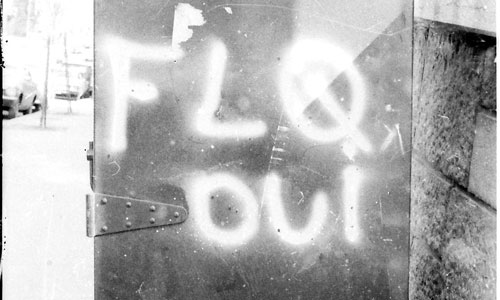

The paramilitary group that changed Quebec forever

In October 1970, Canada was gripped by an act of political violence that seems downright bizarre to those who don't know the history of the province of Quebec.

The October Crisis, as it was later called, drew international attention to the country's long conflict between English-speakers and Francophones. Masterminded by the militant organization Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ), the group's members committed a number of violent acts, including the kidnapping and murder of the province's deputy premier, Pierre Laporte.

The activist group had long been building up to this point, using hundreds of acts of violence and impassioned commentary to help draw attention to its aims to split Quebec from the broader Canada. FLQ members believed that Francophones had been marginalized culturally—perhaps best exemplified by the title of this book (which, word of warning, has the N-word in its title).

The book, written by Pierre Vallières while in a New York prison in 1968, tried to draw parallels between French-Canadians and the civil rights movement in the U.S., which was hitting a crescendo that year. Much like African slaves who were brought to North America unwillingly, Vallières argues, working-class French-Canadians have been held under an aristocratic regime for too long.

Vallières called for the use of violence in the book, and two years later, he got it. FLQ took an action so dramatic that it required the Canadian government to enact the War Measures Act. They kidnapped a political leader, they killed him, and they claimed the action in the name of revolution.

But the actions of the group had the opposite effect—rather than leading to armed revolution against what was believe to be an unjust government, many Canadians supported the move to use the War Measures Act, despite the obvious civil liberties concerns. Even the KGB was concerned that the group's actions in the name of Marxism would be tied to them—and launched a coverup.

And Vallières himself, who received a one-year suspended sentence for his ties to the kidnappings of Laporte and a second man, eventually disowned the calls for armed action even as he supported the end results.

"It is obvious that October was a turning point in Quebec's history," Vallières told The Harvard Crimson in 1971. "The October events reflected the deep aspirations for freedom in the Quebecois."

It did reflect such aspirations, but those aspirations gave way to a more traditional political movement, one that has built nationalist sentiment in Quebec, but along the lines of the traditional party system. Advocates of Quebec nationalism haven't won the war yet, but they've picked up a few battles along the way.

The most important stories are often the ones that don't have easy-to-swallow plot lines. Cultures that face norm-shaking challenges like those that cause a diaspora to form—whether from a volcano eruption or the kind of human rights misdeed that many believe still hasn't been fully paid for—often evolve in interesting ways outside of their collective norms, taking things that are common in their world but translating them into someone else's.

You don't need a shark-fin taco in front of you to know that a fish out of water will eventually figure out ways to make unusual new experiences work for them.

:format(jpeg)/2018/11/x4qrkonsgdua3zzfkrmx--1-.gif)

/2018/11/x4qrkonsgdua3zzfkrmx--1-.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)