Lemony Fresh

Lemon juice has long come in containers shaped like lemons. In the U.K., the containers hold an important legacy—both with pancakes and the legal system.

“This same lemon juice, contained in glass bottles, has been selling in groceries for years. Now it has received fresh impetus because a year or two ago some smart container designer persuaded its manufacturers to sell it in lemon-like containers which help justify the claim to real lemon juice.”

— Alice Hughes, a syndicated columnist, discussing the rise of lemon-shaped plastic containers, which became common in the United States and the United Kingdom in the 1950s. Such devices were developed by a British firm, Edward Hack, Ltd., in the 1950s, though a number of American companies quickly copied the idea. However, a legal document suggests they originally came from Italy in the post-World War II era.

An example of the plastic lemon form. (Drew McLellan/Flickr)

Why lemon juice is so perfect for this kind of container

There’s no reason why lemons, specifically, have to be the only type of juice sold in a container that looks like the original product. (OK, limes are as well, but they’re kind of a similar deal.) But a big reason may have something to do with the specific use case for lemon juice.

Simply: It’s usually not a beverage on its own, but an ingredient, which makes it a perfect match for squeeze bottles. Even before the lemon-shaped product took hold, the plastic squeeze bottle was gaining promise as a potential household tool. A 1953 Chicago Tribune article highlighting new ideas for household products from recent tradeshows showed off a few plastic squeeze bottles, along with a lemon squeezer shaped like a fish.

“Plastics are being used more and more in household items,” the article claimed, as it showed examples of such bottles being used for window cleaners and and dampening laundry about to be ironed.

So, that gets us about halfway there—squeezable plastic products were about to take over the kitchen. But why, specifically, lemons?

In 2015, Beach Packaging Design, an industrial design firm, did some digging into this curious object, which seems to be everywhere without much of an explanation as to how it became so common. And ultimately, they came to the conclusion that a designer named Bill Pugh deserves the credit for coming up with the idea for this wonderful device.

Pugh was the chief plastics designer for a company named Cascelloid, which was the only company in the United Kingdom—and one of only two companies in the world at the time—that had a machine that was able to blow plastic bottles into a molded shape.

Per his 1994 obituary in The Independent, Pugh created a mold out of a combination of wood and lemon peel, recreated that mold with plaster, played with the shape as much as possible, and eventually came up with the perfect form.

This was one of many molded plastic products that Pugh’s team designed in the roughly two decades he worked with Cascelloid. He was an artist of sorts, and his medium was molded plastic.

“He was patient and a perfectionist,” the obituary stated. “In similar vein he made amusing plastic fruits, a gaudy tomato-shaped ketchup bottle for cafe tables, and a range of nasal sprays.”

They tried other devices for this idea. But in terms of combining novelty and function, the lemon hit all the bases—you only need a little lemon juice at a time, and it needs to be stored for long periods. Hence, that's why we have this for lemons (and limes) and not, uh, oranges.

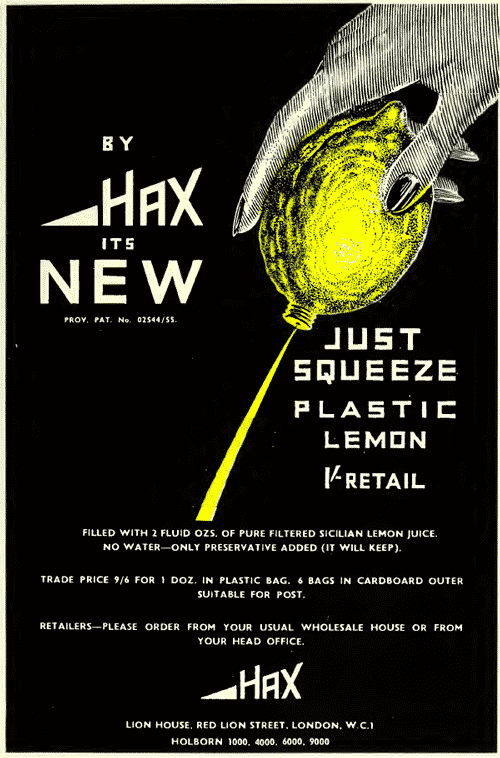

A Hax Lemon Juice ad in a 1955 edition of The Chemist and Druggist. (via Beach Packaging Design's "Box Vox" blog)

Originally, Pugh’s lemony creation was built for a firm called Edward Hack, Ltd., which reportedly assisted in the creation of the plastic lemon by putting much work into finding the perfect specimen. The lemon, initially, was sold under the brand name Hax.

But there was a problem: around the same time, this other guy named Stanley Wagner came up with a very similar lemon idea, which he had briefly sold under the Realemon brand name until he had been called out for infringing an American trademark.

“It’s also interesting to note how little is made of Wagner’s obvious trademark infringement,” Beach Packaging Design pondered in its article. “Coldcrops, Ltd. initially passed off their lemon juice packs as the American ‘Realemon’ brand and then, ‘after an objection by the then Board of Trade,’ simply shortened the name to ‘Realem.’”

(More on ReaLemon in a bit.)

There was briefly a legal battle between the two sides, but eventually, Reckitt & Colman swooped in, acquired the rights for the plastic lemons from both the Edward Hack and Stanley Wagner elements, and soon enough, “Realem” gained its current name, Jif.

(Which, it should be said, is better known as a peanut-butter-related brand name in the U.S.)

71%

The percentage of the annual sales of Jif plastic lemons sold ahead of Shrove Tuesday, according to a 2012 Marketing article. (For Americans and anyone else who isn’t British: Shrove Tuesday, also known as Pancake Day, is the day before Ash Wednesday. In other words, we literally just finished Shrove Tuesday, so no lemon-juice-seasoned pancakes for you.) The British lemon brand, thanks to some clever marketing, has long been closely associated with the pre-Lent event, to the point where the day is called Jif Lemon Day in some quarters.

A Jif lemon. (Gin Soak/Flickr)

How a marketing war over plastic lemons became an important British legal case

The Jif lemon wasn’t a real lemon, but it had marketed itself as a clever substitute for nearly 30 years by the time it faced the first true challenge to its domination.

In 1985, that challenge came in the form of what could best be described as an American invasion—one, notably, that had previously given the lemon brand headaches. The U.S. company Borden, which then owned the ReaLemon brand and was doing pretty well selling lemon juice to people throughout Europe, saw the success that Jif was having with its plastic lemons in the U.K., and decided that it wanted in on this market.

ReaLemon, which was already common in the U.S., had came up with its own variants on the lemon design, all of which played on the fact that lemon juice was commonly sold in a form that mimicked the natural product. This proved too much for Jif owners Reckitt & Colman, who ended up suing Borden over its too-close-for-comfort marketing.

This highlighted a problem for Reckitt & Colman: The design of its lemon made its product distinctive in plastic form, but effectively impossible to trademark.

“The purity of this idea, though, exposed the brand to imitation and costly litigation,” brand consultant Silas Amos suggested in a 2012 Marketing article. “Perhaps adding one ‘twist’ to the lemon design might have turned an obvious idea into a more distinctive (and protectable) brand?”

That made the legal case around Reckitt & Colman Ltd. v Borden Inc, decided by the House of Lords in 1990, an important part of British case law, as it created a test for proving whether a product deserved legal protection despite otherwise being generic—a concept known in British law as “passing off.”

The gist of the three-part test, as formulated by Lord Oliver of Aylmerton:

- There must be an existing reputation that the public carries with the original product or design. (check)

- The competing product creates confusion or misrepresentation in the market, whether intentional or not. (check)

- There are signs that the confusion created by the competing product negatively impacts the bottom line of the original one. (double-check)

Reckitt & Colman easily hit all three parts of this test, and it was assisted by the fact that they held a monopoly of sorts on plastic lemons until ReaLemon came along.

“[A]lthough the common law will protect goodwill against misrepresentation by recognising a monopoly in a particular get-up, it will not recognise a monopoly in the article itself,” Lord Oliver wrote in his legal opinion. “Thus A can compete with B by copying his goods provided that he does not do so in such a way as to suggest that his goods are those of B. Lawful competition will not be restricted by the common law.”

As a result of this case, Borden wasn’t barred from making a plastic lemon that looked like a real one, but they had to put much more work into ensuring that they weren’t simply succeeding by creating marketing confusion with the Jif lemon.

The brilliance of the design of the Jif lemon, in some ways, is also its downfall.

From a marketing perspective, the idea behind this bottle was easy to start with as a branding idea—because, effectively, Mother Nature had already done most of the branding work for them. All they had to do was give it a little squeeze.

A video of Jif lemons being manufactured.

But the instant familiarity and innate novelty only goes so far. If another company attempts to sell a lemon in the same vein as Jif, the company’s current owner, Unilever, isn’t afforded the same kinds of protection for the brand that other kinds of products might earn. In fact, the lawsuit itself was something of a Hail Mary pass to salvage some form of control over the brand’s destiny. Fortunately for Jif, it worked.

Such cases are notoriously difficult to win as well, even when trademark law is on your side. Around this time last year, Procter & Gamble sued a U.K.-based supplier for a store-brand knockoff of its Head & Shoulders shampoo, claiming the private label mimicry represented copyright infringement. (It later filed a similar suit in the U.S.)

Part of the problem for Procter & Gamble, and other companies running into branding issues of this nature in the future, is that the Reckitt & Colman ruling set a standard few other companies can reach without what Jif had—that is, a solid generation of goodwill and a holiday nicknamed after the product.

“Reckitt & Colman was successful in its claim,” the design firm Coley Porter Bell wrote on its blog. “However, the uniqueness of the squeeze lemon packaging set the bar very high for brands following them into court with a complaint over passing off.”

You can’t trademark nature, but sometimes your particular squeeze on the issue is what sets you apart.

--

Clarification: An early mention of a fish-shaped lemon squeezer in the article made it sound like it was a squeeze bottle. In fact, it actually squeezes real lemons. Sorry that was confusing; we cleared that section up.

:format(jpeg)/2017/06/tedium022817.gif)

/2017/06/tedium022817.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)