Purple Copyright Eater

When Prince died, he left behind a massive legacy of music. He left behind an equally massive legacy of copyright enforcement. Here's why.

Today in Tedium: In losing Prince Rogers Nelson, we’re losing a lot more than a idiosyncratic pop star who defined an entire New Power Generation. We’re losing the last link between our current remix-heavy culture (which, let’s face it, this newsletter wouldn’t exist without) and an era when ownership of creative work was treated as an end-all-be-all. Here was a guy who started the internet era sporting a name that literally could not be searched, who forced lawsuits over barely-noticeable renditions of his songs in YouTube clips, and who made a lot of creative stuff that nobody will likely ever see. For all the groundbreaking work he created as a musician in the 20th century, his approach to the internet and copyright was shockingly old-school, and one that should be studied for centuries after his passing. So why was Prince such a stick-in-the-mud about copyright? Today’s Tedium tries to answer that question. — Ernie @ Tedium

one

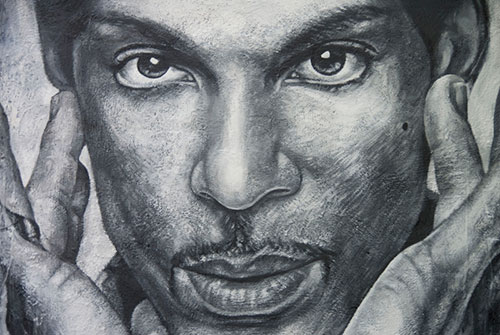

The number of patents granted to Prince throughout his career. The patent, which he received in 1994, was for a keytar shaped like, well, something Prince would invent. It was giant and ornamental in nature, with two pointed spikes at the top, closed loop carved into the upper body, and a lower body that looked kinda like the bottom of a Stratocaster. Much like his primary name during the latter half of the ’90s, it’s better viewed than explained, so here’s a picture of Prince playing the keytar he invented.

(via Wikimedia Commons)

How Kevin Smith got roped into creating a documentary for Prince, and why it was never released

Unlike other lost stars like Jeff Buckley, J Dilla, or Nick Drake, it will be a long time before Prince’s vaults are finally emptied of their contents.

If Prince’s next of kin really wanted to, they could release a new album by the pop superstar every year for the next quarter-century, and they still probably wouldn’t be done. Prince was an insanely self-conscious editor of his own work and image, and he recorded dozens of music videos and created dozens of albums that have never seen the light of day. (There is a Wikipedia page dedicated to this, and it is one of the longer Wikipedia pages you’ll see this week. It’s probably not even complete.)

The thing that revealed the ultimate scope of Prince’s archive of creative work wasn’t a spare statement about that the Paisley Parker once made to an interviewer, nor was it a bootleg or missing hard drive somewhere. Instead, it was a speech Clerks director Kevin Smith gave to an audience of college students as part of his An Evening with Kevin Smith film series 15 years ago.

The 30-minute speech, which has garnered more than a million views on YouTube, is impressive for Smith’s storytelling skills—it’s not easy to tell a single story like this oratorically for half an hour straight—as well as the sheer weirdness of the story.

In a nutshell, here’s what happened: The director, at the height of his box-office powers, attempted to get a Prince song for Jay & Silent Bob Strike Back, but instead got roped into making a documentary with the artist, despite the fact that he had no experience with the filmmaking form. He spent roughly a week at Prince’s Paisley Park with a group of Prince’s biggest fans, with the Purple One only showing his face to the group on very rare occasions.

Prince was apparently a fan of his movie Dogma, and wanted to do a movie about religion. Smith attempted to demur, a tall task when it comes to Prince.

“He’s like, ‘You know what, you’ll do a great job, I have faith in you,’ walks away. And I’m like, ‘Oh my God, I’m making a documentary! I don’t fuckin’ know how to make a documentary, I’ve never made a documentary,’” Smith recalled to a Kent State University audience.

After all that work—which he did essentially for free, by the way—the unedited footage was put into a vault, and has never seen the light of day since. Because that’s what Prince does.

“Prince has been living in Prince world for quite some time,” Smith recalled of one conversation with a Prince associate. “She’s like, ’So, Prince will come to us periodically and say things like, “It’s 3 in the morning, in Minnesota. I really need a camel. Go get it.“’”

Prince apparently struggled to understand why these kinds of tall orders, which he made frequently, weren’t possible.

“He’s not malicious when he does it, he just can’t understand why he can’t get exactly what he wants,” the associate told Smith.

Despite the headaches Smith went through, he ultimately was unable to get the Prince song he wanted, though he did get Prince protégés Morris Day & The Time (“the greatest band in the world,” according to Jay) to play at the end of the movie, which is sort of a nice consolation prize.

We may never see the movie, but you gotta love the story.

“The sites that were targeted in this suit are ones where there was commercial activity. The Artist is very smart. He knows what a fan site is and how important they are. He also is smart enough to see when it’s crossed over into a place where it’s unfair to him to be profiting from things he’s created himself.”

— Lois Najarian, a publicist for The Artist, discussing with MTV the copyright lawsuits he filed against nine websites and two fanzines after they used the unpronounceable symbol that then represented his name. Yes, this is correct: Prince once sued his biggest fans for referring to him as his legal name, because that legal name was a symbol that he copyrighted in 1997. This was a big shift in behavior for The Artist, who once handed out floppy disks to news outlets with a custom symbol so that he could have his unpronounceable name included in news articles.

Why was Prince so protective of his copyright?

In 2013, the Electronic Frontier Foundation gave Prince a lifetime achievement award, the first such award the group had ever given. It was not because Prince was an amazing guitarist and songwriter, even though he was obviously both of those things.

The award the group gave him? The Raspberry Beret Lifetime Aggrievement Award, in honor of his groundbreaking use of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act to prevent fans of his music from publishing his tunes or image anywhere he didn’t want them to be. Prince tried to prevent his fans from posting videos they personally shot of him performing a Radiohead song at Coachella. He was the first person to file takedown notices against Vine users. He even, through his record company, fought a lawsuit against a mom who shot her baby boy briefly dancing to a barely-audible clip of “Let’s Go Crazy” playing in the background.

Prince lost Lenz v. Universal last year, but he never saw an opportunity to attempt to protect his copyright that he didn’t like.

In 2007, for example, he announced his plans to sue both YouTube and Ebay for allowing his own fans to profit off of, or even enjoy, his work. He even went so far as to hire a company, Web Sheriff, to basically remove any reference to his music they could find.

“In the last couple of weeks we have directly removed approximately 2,000 Prince videos from YouTube,” the company’s managing director, John Giacobbi, told Reuters in 2007. “The problem is that one can reduce it to zero and then the next day there will be 100 or 500 or whatever. This carries on ad nauseam at Prince’s expense.”

In some ways, Prince was early to this game; the music industry as a whole has been raising heck about it lately. But in other ways, Prince went further than any other artist likely ever will.

For all his creative thoughts and approaches, he’s a capitalist at heart, and one that came along during the era of MTV. And he approached the internet through that lens throughout its existence, something highlighted by the fact that, in 2010, upon the release of an album inside copies of The Daily Mirror, he declared the internet “dead.” As Clifford Stoll can tell you, that’s a dangerous declaration to make, but the important thing to understand is why Prince declared it dead.

“The internet’s like MTV. At one time MTV was hip and suddenly it became outdated,” he told the Mirror at the time. “Anyway, all these computers and digital gadgets are no good. They just fill your head with numbers and that can’t be good for you.”

Basically, he approached the digital revolution as just another distribution approach for that creative output, rather than what it actually was: a world-shaking thing. MTV disrupted one industry, music; the internet made that industry shift look like a record skip. It forever changed the way we think of copyright, and that change wasn’t compatible with the way that Prince, a musician famous for wanting to carefully sculpt every piece of art he releases to the world, thinks of the ownership of content.

And to prove this point, he shoved records inside of dead trees.

Love him or hate him, Prince was the last vestige of an old way of producing music. He craved complete creative control, and when he didn’t have it, he publicly raised issues with those who didn’t give it to him, whether their name was Warner Bros. or Stephanie Lenz. He was also rich, so he could afford to go after people who he felt were misrepresenting his image on the internet.

For decades, Prince was a masterful curator of his own image; that’s why he has 50 music videos sitting in a vault somewhere that may never see the light of day, along with a Kevin Smith movie, and probably a lot of other things, too.

He attempted to do the same thing online. And he failed.

:format(jpeg)/2018/01/fy1cvyyspwxjraaau8er.gif)

/2018/01/fy1cvyyspwxjraaau8er.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)