We're Going Viral

The computer virus has been around for more than 40 years now, and it's caused lots of panic (and occasionally some damage) over the years. But don't freak.

The day the media learned what a computer virus was

There were computer viruses before March 1992, but few of them really drew any sort of attention before the Michelangelo virus gave media outlets something that had been missing from prior coverage of computer security phenomena—a big, meaty story hook.

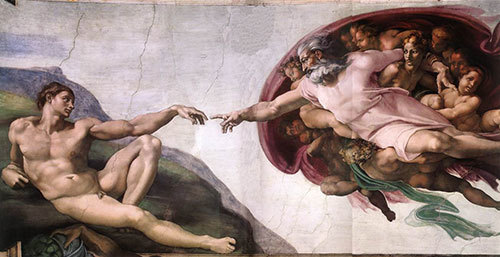

Despite being a variant of a much funnier virus, it had a clever name—inspired by its shared birthday with the famed artist—a set date when something was expected to happen, and a payload that could be disastrous.

On March 6 of each year, the boot-sector virus would garble up all the boot-sector data on a hard drive, making it inaccessible to the average user. It was a ticking time bomb, and one that could be easily explained in a news story. The result was that it became the perfect news story to freak out the public.

You could thank John McAfee for a big part of this: McAfee, then a prominent antivirus-maker who was the chairman of the Computer Virus Industry Association, drew a ton of attention during the late '80s and early '90s by being a willing source to any reporter who needed one. This came in handy for McAfee, a man who's never been shy about self-promotion.

"On March 6, if you boot an infected system, there is a total garbling of all the data in the hard drive," McAfee said at a computer security conference immediately before the virus hit.

He wasn't the only one, but McAfee's pitch was particularly effective in an era when people barely even knew what a computer could do.

March 6 came, and March 6 went, and while a few computers got hit, it was nowhere near the holy-crap moment that the media made it out to be.

"It was the biggest non-event since Geraldo broke into Al Capone's tomb," ZDNet aptly put it in 1998.

Reporters, as you might guess, felt duped by the whole thing.

"In reality, many of the predictions were suspect," tech writer George Smith argued in the American Journalism Review back in 1992. "Those making them, often computer security product vendors or closely related industry associations, usually stood to profit from the widespread coverage. And many reporters bit hard."

It wasn't be the first time that reporters overhyped a story about computer security, and it wouldn't be the last.

"Thanks largely to False Authority Syndrome, users now often panic at the first sign of any odd computer behavior, sometimes inflicting more damage on themselves than a virus could do on its own (assuming they even had a computer virus in the first place)."

— Rob Rosenberger, a noted skeptic on computer security issues, discussing the way that people freak the hell out when they hear about a computer virus. In a 1997 article on the phenomenon, he specifically takes aim at McAfee and other computer security experts, who he says are often driven by the financial benefits of promoting data security concerns. This, he says, is worsened by the fact that when media outlets talk to sources regarding virus stories, they're often talking to people that actually sell the software, instead of security experts.

Five computer viruses that made their mark on history

- The CIH virus, which was borne out of Taiwan in 1998, was much worthier of the hype that followed Michelangelo. The Windows-era virus, better known as Chernobyl, was able not only to erase a hard drive but to rewrite a computer's BIOS, which made the machine unusable. It didn't spread through email, but through infected apps on CDs. Here's a YouTube clip of CIH destroying a computer.

- The first virus wasn't really dangerous, nor was it called a virus at the time. It was simply an attempt to see if a program could self-replicate. That program, called "Creeper," ran on the Digital PDP-10 mainframe system and simply replicated the phrase, "I'm the creeper, catch me if you can!" Eventually, a fellow virus called "Reaper" followed behind, attempting to catch "Creeper."

- Often, Mac users like to make fun of Windows users for the number of viruses they run into, but it's worth keeping in mind that older Apple II models were hit by viruses quite often. The most famous ones were called CyberAIDS and Festering Hate, which sound like two of the best ever death metal bands never created.

- The Code Red virus, named for the famously cherry-flavored variation on Mountain Dew, spread incredibly quickly throughout the world through Microsoft's IIS web server, which a ton of websites used back in 2001. The virus even hit the White House.

- If you had a Nokia phone back in 2005, there was a chance you might have gotten hit with a virus back then. No, really: The Commwarrior virus would pretend to be an MMS message from your friend, but when you opened it, you learned it wasn't very friendly at all. It was one of the first viruses to hit a mobile device.

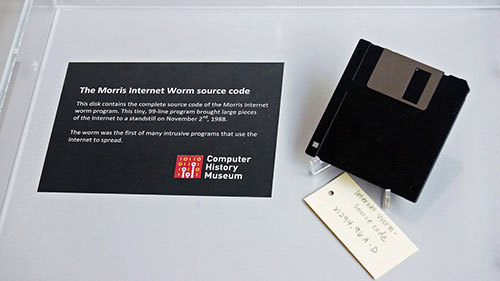

The co-founder of Y Combinator created a worm that almost broke the internet in 1988

When discussing the career of Robert Morris, the word "atonement" comes to mind.

Morris, as a partner in Y Combinator, has helped startup owners across the spectrum polish their ideas and turn them into important products that we use daily. (Example: The file I'm using to write this document is being synced by Dropbox, an early Y Combinator success story.)

But like many of the people who parlayed their tech skills into startup success, his record on the youthful indiscretion front isn't a clean slate.

That's not a knock on him; what he did was technically impressive. But the Morris Worm, as his grad school side project came to be called, really screwed up the internet's backbone at a time when it was pretty vulnerable.

"I remember the NBC Evening News devoting less than 30 seconds to the topic," online user Francis Litterio wrote on a page dedicated to the worm. "If an equally severe disruption of the Internet were to happen today, the President of the United States would probably hold a press conference to calm the nation."

The year was 1988, and Morris, as a grad student at Cornell, decided to program an app that would self-propagate through all the Unix machines that made up the internet at the time—a network that, in 1998, was mostly made up of businesses and academics.

Morris' goal was to create the first botnet, essentially to prove he could do it. But while the worm failed at that goal, it was particularly great at replicating itself numerous times on different machines—something that happened basically by accident due to the way it was coded. In the end, the worm was so effective that universities had to go offline for a while so as not to damage their equipment.

As a result of the stunt that got out of hand, Morris became one of the first people charged under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986—the same law that early Y Combinator alum Aaron Swartz was infamously prosecuted under a quarter-century later. Morris narrowly avoided prison time for what he did.

To this day, Morris doesn't really talk about it—though in a lot of ways, his worm had positive side effects, by exposing just how poor security was on many university networks. People didn't care about password security until Robert Morris came along. Now, security is treated as an immensely important part of running a large network. And Morris, who currently serves as an assistant professor in MIT's Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, has become a person worthy of emulating—something that can't be said about John McAfee these days.

"He has not tried to make any money or work in this area," Purdue University computer science professor Eugene Spafford said of Morris in an interview with_The Washington Post_. "His behavior has been consistent in supporting his defense: that it was an accident and he felt badly about it. I think it's very much to his credit that that has been his behavior ever since."

Now, all of this is not to say that viruses aren't dangerous. Malware will continue to be an immensely annoying scourge, whether it affects your laptop, your phone, or your Jeep Cherokee.

But the thing is that we need to be honest with one another about what malware is, and why we need to be worried about it. The reason that many of these viruses have spread over the years is because they prey on people's worst instincts. We want things to be simple, so we pick obvious passwords. We want to believe that our email is safe, so we open things from people we think we know. And when we see information online, we want to innocently believe it's leading not leading us astray.

The truth is, John McAfee was right that we have to be concerned, but Rob Rosenberger was also right that we need to keep our BS meter working. The truth is somewhere in the middle.

In an era when a site called Download.com is more likely to infect your computer with junk than your email is, you have no choice: you have to let your guard up, at least a little.

But don't panic. Use your head.

:format(jpeg)/2018/11/ncrwcda0af6mqxkala6ib.gif)

/2018/11/ncrwcda0af6mqxkala6ib.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)