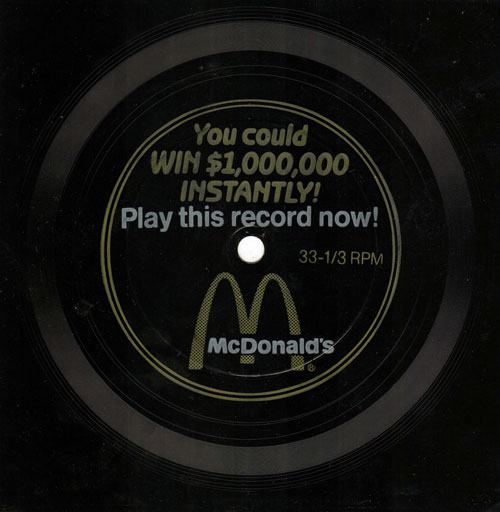

Today in Tedium: In many ways, writing a Tedium piece is like an ongoing search for a “white whale” (or a Baby Beluga, if you will)—a hunt to find a great story and give it some cultural context before it’s lost to history. One such story I’ve always looked longingly at was the tale of the million-dollar McDonald’s record, a record that, quite literally, was one in 80 million (meaning that 79.999999 million weren’t worth a million bucks). I always wondered who won that record. I didn’t get to tell that story; KCRW, in its “Lost Notes” podcast, did last month. Game respects game. But the flexi disc has a history beyond that McDonald’s record that showed up in newspapers around the country in 1988. And tonight’s Tedium talks all about it. — Ernie @ Tedium

Like the App Store, but good: Are you a Mac user? Check out SetApp, which is like Spotify for your desktop—and has tons of cool, useful apps you'd never find on the Mac App Store. Sign up for a free trial.

Wanna advertise here? Learn more over this way.

“The inventor claims that the material of which the plates are made is strong enough to stand passage through the post, and he holds that it will be just the thing for engaged couples or for people who wish to insult one another by post.”

— A 1905 article in The Sketch, discussing the rise of the “talking postcard,” an invention that dates to the first decade of the 20th century, though it’s not entirely clear who exactly invented it—this article claims it was invented by a Viennese man, while a 1906 Chicago Tribune article (on the front page, even!) claims it was a Frenchman, and a more contemporary source says it came from Germany. Whatever the case, the cards became an early craze by the middle of the decade, particularly becoming popular in France. The device represented an early craze for the idea of records on nontraditional mediums, but the idea eventually faded from view for a few decades.

The infamous McDonald's "Million Dollar Song" flexi disc. (A. Currell/Flickr)

In the U.S., at least, flexi-discs were the ultimate marketing material

When Sir Winston Churchill died in 1965, National Geographic magazine did something unusual—it brought its readers a multimedia experience, albeit in analog form.

The magazine dedicated a commemorative issue to Churchill, one of the most important leaders of the 20th century, but almost as if to emphasize the point, the magazine had famed newsman David Brinkley narrate a record that featured audio “scenes” from Churchill’s funeral, along with clips of some of his most famous speeches.

The two-sided 12-minute recording, which can be heard on YouTube, makes a fascinating aural document, but it also represented something else: It was a coming out party for the flexi-disc, thanks in no small part to the fact that the record went to 4.5 million people. That’s right—the record was technically four times platinum before it even reached a single eardrum.

According to a 1967 Chicago Tribune piece, the record was a massive hit for Eva-Tone, the company that came up with the American version of the flexi-disc in 1962. According to the Museum of Obsolete Media, it was available in other countries, including the United Kingdom, before that—which explains why The Beatles were one of the technology’s earliest users, putting them to use for their often-avant-garde Christmas records.

Eva-Tone was the driving force behind the device’s success as a marketing medium, particularly between the 1960s and 1980s.

(The fact that it was a coming-out party based around the death of a key figure during World War II also highlights the fact that record-playing technology had evolved significantly during the postwar period.)

Soon, the discs, which cost between 4 and 6.3 cents to produce at the time of their initial release, were being used not to honor iconic world leaders, but to promote advertising. In 1966, for example, Insulite Ceilings produced a flexi-disc for Popular Mechanics, featuring comedians Bob and Ray talking about “The Quietized Home.”

And it expanded from there. Beyond the infamous McDonald’s record, which was perhaps the best-remembered moment for the flexi-disc among those born after 1980, the concept of records produced with materials other than thick vinyl gained a lot of steam between the 1960s and 1970s.

Cardboard, for example, became a popular promotional medium, one used in a variety of ways, including as a cereal-box prizes, in which the record itself was actually printed on the box—perfect for prefab bands like The Archies. The Jackson 5 also got in on the cereal box action, and baseball card maker Topps at one point did a deal with Motown Records to put artists like The Four Tops onto pieces of embossed cardboard.

Not bad for an alien.

And of course, McDonald’s wasn’t the only fast-food chain to get in on the craze. Burger King—or should we call them Pancake King?—once created a series of records promoting the TV show ALF. Really.

The concept of the thin record had extreme novelty and even more extreme marketing value, obviously, and the Tribune article implied a wide variety of uses for the flexi-disc, with Eva-Tone’s Norman Welch making the case for using the inexpensive records not simply for advertising, but for employers hoping to simply convey information to their employees—an idea that might have had some value in the days before VHS.

“This is not a gimmick,” Welch somewhat unconvincingly said. “It’s a good program. But we still have to educate people to our business because it’s so new.”

Of course, the medium was interesting, but it wasn’t perfect. As writer Phil Strongman wrote for Ars Technica last year, the records were so light that they wouldn’t properly play in many turntables with heavy cartridges. This meant that the record had to either be played on top of another record, or held down by a coin—not exactly ideal, but considering consumers were working with records in magazines or on cereal boxes, the compromises made sense.

(In case you want to do more digging into the world of Flexi discs, be sure to check The Internet Museum of Flexi/Cardboard/Oddity Records, a website full of strange vinyl-like ephemera.)

1977

The year that Interface Age magazine produced the “Floppy ROM,” a unique experiment in trying to share a program with its readers on a flexible vinyl disc. (You can see a photo of the disc, encoded with a 4K BASIC program, here.) Eva-Tone worked closely with the magazine’s publisher and numerous other parties in hopes of producing a medium that would allow for the cheap distribution of data, as other formats of the time, such as tape, weren’t up to the task. “This event is the achievement of many manufacturers and retail computer stores who have worked together on this project,” Interface Age publisher Robert S. Jones stated in an editorial discussing the creation of the disc, which may be the world’s most obscure data format. The full issue is on the Internet Archive.

Poland's Pocztówki Dźwiękowe, or sound postcards. (Piotrm00/Wikimedia Commons)

How the flexible disc created surprising subcultures in some parts of the world

Flexible discs—whether made of vinyl, plastic-covered cardboard, or something else—have many general disadvantages compared to vinyl records. For one thing, the discs aren’t built to last. The sound quality’s lower. They will degrade quickly when repeatedly played in a standard record player. And they have an ugly tendency to warp.

But on the other hand, flexible discs tend to be great ways to mask the distribution of music under oppressive regimes.

A great example of this is in Poland, which was under a Communist regime from the end of World War II in 1945 to 1989.

Pocztówki Dźwiękowe, or sound postcards, as a result, became something of a workaround for many Polish citizens looking to have access to the popular music of the day at a time vinyl was difficult to get access to. This allowed locals to get around censors that were skeptical of rock music, to the point that locally produced rock music was given a different name—“mocne uderzenie,” or “big beat”—to avoid affiliations with Western music.

Part of the reason sound postcards worked so well for this was that they could be user-produced, with the help of a kiosk, allowing for copies to be made—including with a voice introduction before the sound itself.

These records, generally, did not get any sort of notice outside of Poland until the late 2000s, when an Australian expat and music festival organizer named Mat Schulz first noticed the unusual postcards in open-air markets and found his curiosity intrigued.

“There’s no correlation between the image on the front of the cards and the song,” Schulz noted in an interview with Public Radio International in 2010.

Despite being postcards, they appeared to have had rarely been sent to anyone. Instead, they generally were collected much the way actual records were.

“Although similar objects existed elsewhere, I later found out that in communist Poland sound postcards were incredibly popular—an indication of the strong desire Poland had to connect with The West via music,” Schulz wrote in Biweekly.pl in 2011. “They had their heyday in the 1960s and 1970s when it was difficult to buy real vinyl. People would purchase these cards and take them home to play on portable record players.”

The portable record players were often as cheap as the cards themselves, and had a specific vibe to them. The Bambino players were mono and have a tendency to break down—meaning that finding a working one is challenging in the modern day.

Similarly, citizens of the Soviet Union, under many of the same rules as Poland, found a unique and unusual way to take their interest in Western music underground. The solution in that country, however, took something of a more stark edge: The records, rather than being pressed on postcards or other kinds of flexi discs, were often put on old X-rays, creating a startling, often disorienting disconnect between the song and the material it was playing on. The resulting records were called “roentgenizdat,” or “bone music.”

Roentgenizdat, or bone music. (Dmitry Rozhkov/via Wikimedia Commons)

Like with Poland's postcards, a cultural outsider helped bring them to public attention outside of their home country. Musician Stephen Coates of the British group The Real Tuesday Weld, found one while on tour—again, in an open-air market—and was so intrigued by the finding that he launched a project devoted to assessing the unusual records—and even produced a book based on the story of their creation.

Coates, in a TEDx presentation he did in Krakow, Poland, explained that bootleggers, working around tough state censorship, took advantage of rules of the day that required hospitals to throw out old X-rays after a year, to avoid fire hazards. The bootleggers happily took the X-rays off the hands of the hospitals, and used them to engrave flexi discs of their own. In fact, the X-ray discs actually predated the flexi discs produced in the United States by a number of years.

These records, also nicknamed “ribs,” would become some of the most fascinating examples of bootlegging, in no small part because of the sheer dichotomy between source material and medium.

While Americans were listening to jazz music on records that featured immaculate cover designs by folks like Alex Steinweiss, people in the Soviet Union were being arrested for producing records on glossy X-rays adorned with broken bones.

As cultural differences go, you don’t get more stark than that.

“Most famous were the ‘talking stamps,’ small rounds of grooved rubber that could be spun on a phonograph. One played the Bhutanese national anthem; another, a spoken-word stamp, had Mr. Todd delivering a very concise history of Bhutan.”

— A passage from the 2006 New York Times obit of Burt Todd, an American entrepreneur with a reputation as an offbeat adventurer and dealmaker, whose most famous creation is a series of ambitious stamps for the Kingdom of Bhutan. The country’s stamps would take unusual forms, including pictures of world leaders of other countries, 3D paintings, and most famously, stamps that were tiny, playable records—generally produced in rubber, but sometimes in steel that had a tendency to rust. (You can listen to them here.) After Todd died in 2006, his daughter produced an updated stamp that might be the world’s only CD-ROM stamp.

It makes sense, in a way, that as vinyl is seeing a revival, so too is the flexi-disc in its myriad forms.

But with companies like Eva-Tone having fallen well into the past and promotional materials moving away from physical media entirely, the reasons for creating and protecting these mediums are significantly different—and come from a place of knowing one’s history.

Pirates Press, a San Francisco-based record manufacturer that was founded in 2004, took the bold step of creating its own press for flexi-discs, as a way of making it possible for modern acts to take advantage of techniques once used for vintage marketing—or do something else entirely.

(Third Man Records, Jack White’s vinyl-friendly label, has also done fascinating things with the flexi disc. In 2015, for the label’s vinyl release of Jay-Z’s Magna Carta Holy Grail, the label hid a flexi-disc inside of the case for the main album. The flexi disc contained a secret track, of course.)

The company noted in a 2015 NPR article that bands were embracing the flexi-discs as giveaways, or in some cases, as an alternative format for distributing music. The bands, likewise, have noticed the appeal of the discs.

“They're not necessarily a collector in perpetuity,” Deerhoof drummer Greg Saunier told NPR of the target audience for a flexi disc in 2018. “It’s more they’re interested in possibilities, and ideas and sources of inspiration. And it's OK if sometimes those sources are slightly garbled or contain distortion or noise, or if they wear out and remain only as a memory of what they should have sounded like.”

Pirates Press even sells “X-ray” records, just like the ones shared in the old Soviet Union—with a couple of key differences.

“While finding X-rays to press on is nearly impossible, and the audio quality is HORRIBLE, we can EASILY make you imitation ‘bones’ that sound fantastic,” the company states on its website.

It’s fascinating to consider how quickly even highly disposable formats find new life in the modern day.