Today in Tedium: Earlier this week, I got a little grumpy over at Product Hunt, due to an undercurrent of snark around the fact that Netflix still has a DVD service. The reason for this was that too many people were skeptical about whether such a service was still necessary. It absolutely, totally is, and I’ll give you one reason why: Netflix’s DVD service has roughly 93,000 options, while its streaming service (between shows and movies) has fewer than 8,000 options—ensuring that DVDs will have a reason to exist for quite a while. Why such a big difference? Well, it’s because running a streaming service and sussing out the contracts is really freaking hard. (Hollywood is a tough negotiator.) And, by the way, Netflix wasn’t the first to do video-on-demand in this way. In today’s Tedium, we virtually head to Hong Kong, where I tell you about who was. — Ernie @ Tedium

“If interactive television cannot work in Hong Kong, it can't work anywhere.”

— William Lo, the head of Hongkong Telecom’s interactive division, speaking to The Economist in 1998 about why he felt the company’s about-to-launch video-on-demand service, iTV (or interactive TV, no relation to Apple’s long-rumored vaporware), was likely to succeed in the city-state. Among the reasons the telecom firm was so willing to spend $200 million to test the idea: The autonomous territory has one of the world’s highest per-capita incomes; the relatively small size of the region made it easy to cover the territory with fiber-optic cable; and consumers in Hong Kong had a clear taste for both technology and entertainment. Cable television, which only came to Hong Kong in 1993, had saturated 25 percent of the market at the time iTV launched. No matter the case, making iTV happen wasn’t cheap: The company reportedly invested $1.5 billion in the entire project before it had served a single customer.

A prototype of iTV, as shown in an Associated Press news clip. (YouTube)

iTV had really huge ambitions. Almost embarrassingly huge.

In a lot of ways, iTV wanted to be everything to everyone. The promises were massive—far beyond those that Netflix has ever made. That’s because, with the internet relatively young, it in some ways wanted to be the primary way that users experienced those tubes.

A 1997 story about the service from Varsity magazine, a publication of the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s journalism school, highlighted how executives were promising big things, calling the initiative “a 24-hour private cinema and shopping mall at home.”

The piece, featuring an interview from Hongkong Telecom’s Lo, spoke of the concept (already being tested in trials at the time of the piece) in bold terms, including implying that the set-top box would bring impressive levels of interactivity to homes. Banking services were planned. In other words, this wasn’t just a prototype for Netflix, which wasn’t even mailing DVDs by this point, but a juiced-up WebTV.

Helping support the boldness of the claims was the company’s own research. The company claimed that 80 percent of the people they interviewed were likely to want to use a video-on-demand service, and that 70 percent of current cable subscribers would see iTV as a complement for cable—not a replacement.

Lo tried to sell the concept with examples that had clearly gone through the marketing department.

“Imagine you are extremely tired after a full schedule of work,” he told the student publication. “You suddenly remember you have to serve dinner for 20 people tomorrow. You find that there is no food left and the supermarket is closed. Desperately, you just want to watch a good movie to ease your nerves.”

That was the windup. Immediately after came the pitch: “This annoying experience may occur every day in modern people’s lives, and iTV’s services provide a solution.”

There are plenty of innovations that pledge to change the world, from Casio’s promise that it could replace an entire band with a keyboard to … well, WebTV’s promise to bring the internet to your living room. But in some ways, iTV wasn’t looking to change the entire world (at least not at first), but instead make the lives of as many as 6 million people really, really, awesome.

The firm held a launch ceremony for its video-on-demand service on March 23, 1998, less than three weeks before Netflix mailed its first DVD.

Hongkong Telecom didn’t just have to sell the public on the service. It had to build the entire infrastructure, strike the deals, and put all the technology into place for a perfect launch.

But the launch wasn’t perfect.

90k

The number of households that subscribed to iTV at its peak, according to CNN. (The number looks particularly rough in light of the fact that so much money was spent on the service, and that Hongkong Telecom had lined up 40,000 pre-orders.) The service struggled in large part because of a combination of technical issues and consumer confusion.

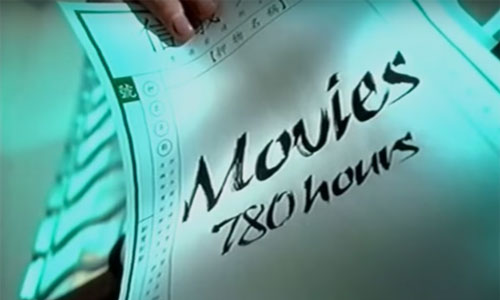

A service with 780 hours of movies seems so quaint nowadays. (YouTube screenshot)

Why iTV failed to live up to the massive pre-release hype

Consumers in Hong Kong obviously had plenty of reason to be excited about video-on-demand, especially as the service was completely new and unprecedented on the world stage.

A commercial for the service sold the potential of a ton of entertainment for the time—780 hours of movies, 95 hours of music, 150 hours of radio, and the ability to go shopping when you weren’t trying to take in any of that entertainment. And the price wasn’t too bad, either—for the first three months, $188 a month in Hong Kong dollars, or about $24 in U.S. dollars.

But the reality of the matter was a bit cloudier. In a 1999 Wall Street Journal article, written about a year after iTV’s introduction, the newspaper highlighted the story of Dennis Leung, a heavy user of the platform.

"Saturday between five and six I was trying to pick a movie, I had my beer, my snacks in front of me, the movie all picked out—and it took me 45 minutes to get the movie loaded," Leung told the Journal.

The problem was that the movie he chose, Batman and Robin, had been loaded by too many users at once, which caused content-licensing issues, and he kept running into an error message. (The error message was not, as it turns out, “iTV is trying to protect you from a terrible movie.” That would be a useful error.)

And more problematic, wrote the Journal’s Christina Mungan, was that the financials—already a pain point due to the infrastructure costs—didn’t add up due to the low subscriber numbers and the set top boxes.

“It charges subscribers at most $35 a month for services that the company expects would be profitable at about $50 a month,” she wrote.

And like Netflix, licensing issues proved a major challenge as well. The device was actually supposed come to market in 1996, but was held up by a film-licensing rigamarole made more complicated than necessary because Hollywood saw Hong Kong as a piracy hotbed, and not without cause.

The result was that the device, expected to revolutionize computing throughout the territory, only caused a minor ripple effect. It proved a better lesson for telecom firms in other countries looking to get into the video-on-demand market than it did an actual standalone business.

iTV was a pioneer. And it took all sorts of arrows.

Janice Lee, a broadcasting executive for PCCW who headed marketing at iTV in the ‘90s, said that the sheer number of things that the platform could do confused the public.

"It was wonderful technology, very ahead of its time," Lee told Businessweek in 2006, “But we were asking too much of consumers.”

Apparently, PCCW felt the same way, because they let the service die on the vine after acquiring Hongkong Telecom in 2000. By 2002, the service was dead.

So the bad news is that iTV flopped in the market. On the plus side, it wasn’t the basic idea that was the problem, but the execution.

And it wasn’t like that $1.5 billion investment was all for naught, either. Hongkong Telecom got in early on fiber-optic cables, and that made Hong Kong an attractive market for the tech sector, which could play with innovative ideas that were still trickling out on dial-up connections in other parts of the world. (It also made people using the internet in Hong Kong very happy.)

While iTV was still gaining its footing on the market, Microsoft scored a deal with Hongkong Telecom to bring Windows-based set-top boxes, a service it called Zoom, to the Hong Kong market.

And PCCW, after acquiring Hongkong Telecom, followed up on the basic idea of iTV and greatly improved on it, creating NOW Broadband, a service comparable to Verizon FIOS that proved much more successful than the initial effort. By early 2006, the company had roughly one-half of the world’s 1 million users using internet-based video-on-demand.

"This time around, we want to train them," PCCW’s Lee told Businessweek in 2006. “Give them enough to chew on, but not too much.”

Video-on-demand did work in Hong Kong, and it did so before Netflix launched its own streaming service in the U.S. It just didn’t succeed with iTV.

Nowadays, 1.3 million people subscribe to it, according to TeleGeography, making it Hong Kong’s largest pay-TV provider. Not bad for a territory currently with a population of around 7.1 million people.

And the service is constantly improving. Here’s proof: Last year, the service’s set-top boxes gained access to Netflix.

In a way, it was kind of like they were going back to their roots.