Editor's Note: After tonight's issue, I'll be out of the office for a bit. Like a CBS sitcom airing in June, expect a couple weeks of reruns.

Today in Tedium: Last week's saga of clock-hacker Ahmed Mohamed has become a political fireball. It's a case of a student who chose to bend the rules of his own education and try to learn things outside of school, only to get punished for it. Many critics of Mohamed in the wake of his arrest seem obsessed with discrediting a 14-year-old, but the odds are best that Mohamed was just a curious 14-year-old who got in over his head. But, in a way, Mohamed's efforts are nothing new. Tech-savvy kids have been screwing with teachers' expectations for generations, and nowhere is this more obvious than the phenomenon of graphing calculators. These devices are immensely hackable, but most classrooms only use a fraction of their capabilities. Here's why. — Ernie @ Tedium

(Wikimedia Commons)

As powerful as Game Boys, and mostly used for the same reason

For roughly two decades, high schools have been giving graphing calculators to students, requiring them for key math classes, and for pretty much that entire time, students have been figuring out ways to use the devices to bend the rules.

Part of this was actually allowed by Texas Instruments, which around 1990 started making graphing calculators that could be programmed in various ways—generally through a variation of BASIC, but also through low-level assembly code, which had a clear advantage for the slow calculator. To this day, the company's TI-84 remains its most popular and widely used, with the TI-83 not far behind.

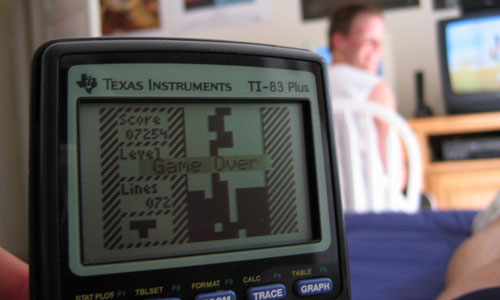

Eventually, the kids got savvy and started learning to program the devices. Naturally, the first programs they built were games, because of course they did. Variations on Super Mario Bros, Pac Man, and Pokémon quickly arrived. The quality of the games got better as the programming techniques got more savvy. Website repositories of said games launched and found lasting popularity. (One such site, TI Calc, has been around for roughly two decades.)

And those kids familiar with hooking up devices to a computer and installing games were suddenly the coolest kids in the classroom. (Or, at least they felt that way.)

I was one of those kids: During the Clinton administration and in the days before USB cables made everything easy, I purchased a flimsy wire that was hand-made by an enthusiast and sent to me via mail, allowing me to plug my TI-82 into my computer's serial port and install programs and games. So I did the same for my classmates that year. I think I charged, but I can't remember how much. Admittedly, I learned more about installing crap on an obscure device using a weak cable that year than I ever did about tangents and derivatives.

I remember playing an old Final Fantasy clone all the way through on my calculator. Clearly my education was effective.

Five things that have been programmed onto graphing calculators

- Despite the fact that graphing calculators don't have much in the way of connectivity, that hasn't stopped programmers from successfully building a web browser for the TI-83.

- Console emulators are challenging to get on graphing calculators, due to the fact that the calculators are roughly as powerful as the consoles. But that hasn't prevented the creation of a Game Boy emulator. (Here it is, playing a Zelda game.) This guy even gutted a graphing calculator and replaced it with a Game Boy Advance.

- The classic first-person shooter Doom has been ported to just about every platform under the sun, and that includes multiple TI calculators. The TI-83 and TI-84 can play this two-color variation on the game, while a version for the TI Nspire gets shockingly close to the PC version.

- Last year, someone put together a project with the goal of getting Super Smash Bros. on a TI-83. It's incredibly simplistic, but they succeeded.

- Most recently, someone figured out a way to get an early version of Android onto the TI Nspire CX.

"The TI-84 was the first platform where I began my interest in game programming, so I will probably always have a little bit of an attachment for it. Plus, I always say that programming for such a restrictive platform really forces you to be creative and work harder to get your work done. If you program something simple for the computer, even if you program it badly it will still run quickly, whereas with a calculator, you need to work extra hard in order to make your code run at a reasonable speed."

— Programmer Alex Marcolina, discussing why he chooses to program apps on a graphing calculator. Marcolina is pretty good at it—he created a version of Portal, a game known for its complicated physics, on a TI-84 calculator. The feat is particularly impressive due to the fact that just 25k of RAM is accessible to programmers.

The political issues surrounding graphing calculators

Calculators have long been controversial with educators. For decades, they raised big, important questions: If allowed in schools, would they create a divide between those who can afford a calculator and those who can't? Will they make students dumber? How does this affect the way that we teach students?

(And we're not just talking the fancy kind, either. Regular calculators with limited functionality are still controversial among some parents of elementary school children.)

For years, graphing calculators struggled to gain acceptance by teachers. One 1994 study on the issue found that 70 percent of teachers who had access to graphing calculators weren't using them in their classes. Part of the issue was philosophy; many teachers wanted students to do the math by hand before relying on the calculator. The devices made things too easy.

Slowly but surely, those complaints have started to fall by the wayside. Standardization helped things—in 1994, graphing calculators were added to the College Board's requirements for teaching AP Calculus, though the restrictions on what kinds of calculators can be used remain fairly strict.

As a result, calculator technology has remained relatively stagnant compared to the rest of the world. When TI tried to update its models to do more stuff—specifically, its Nspire models, which support the creation of spreadsheets—it found that nobody was really all that interested.

"Here's the thing. Some technologies don't change all that quickly because we don't need them to," Alexis Madrigal noted in a 2011 Atlantic piece. "Much as we like to tell the story of The World Changing So Fast, most of it doesn't."

But some of this stuff is artificially mandated by the rules and restrictions of the medium. To this day, some calculators with touchpads (such as Casio's Classpad) aren't allowed to be used during most standardized tests. Your iPhone 6S can run circles around your TI-83, but the limitations of the device are a virtue in testing environments—to put it simply, not everyone in the room will have the latest iPhone, but you can guarantee every student will have the same rough kind of calculator.

And considering that graphing calculators maintain their value largely on the back of standardization in classrooms, anything that threatens this state of affairs becomes a problem. When enthusiasts have tried to stretch the edges of these devices, TI didn't take too kindly.

In 2009, TI found itself the target of controversy among the tech community when it started filing Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) complaints against bloggers who published the "signing keys" used to limit the kinds of operating systems that can go onto TI calculators. The Electronic Frontier Foundation quickly cried foul, arguing that TI abused the act through this action.

"This is not about decrypting copyrighted code so that you can distribute it to the four corners of the Internet," EFF's Jennifer Granick wrote. "This is about running your own software on your own calculator. So where's the copyright infringement in that?"

There may or may not have been copyright infringement happening, but one thing is clear: TI has a lot to lose if the integrity of its calculators is broken.

These calculators highlight an odd dichotomy between education and technology. While designed to teach mathematics skills, programmers and rogue calculator owners have taken advantage of the skills learned in the classroom to program and design applications on simplistic platforms.

In a lot of ways, the best comparison point for early TI calculators is the Raspberry Pi. Like that ultra-cheap, ultra-hackable computer, the advantage of graphing calculators as a programming and computing tool is that they're simple and can be adapted to numerous settings. Unlike the Raspberry Pi, however, your Texas Instruments calculators were never intended for that purpose, and as a result, they created potential distractions for teachers who were focused on teaching a certain curriculum.

But the odd part is that the calculators were arguably more interesting as education tools when they broke the rules. (Or they were really good for playing Mario clones. Either way.)